“Now — the water is boiling,” says Jen Hamilton, calling attention to the pot on her stove. She lifts the pot and places her other hand flat on the cooking surface. She remains uninjured. “It’s safer!” she exclaims, explaining that her cats used to inadvertently turn on the gas on her old stove by bumping the knobs.

“We are now completely electric,” says Hamilton. With the induction stove for cooking and a heat pump for climate control, she and her husband, Phil Salkie, have eliminated the need for natural gas in their home. They even called PGW to have someone cap the gas line to their house and remove the meter from their wall. “That was a wonderful feeling,” Hamilton adds with a smile.

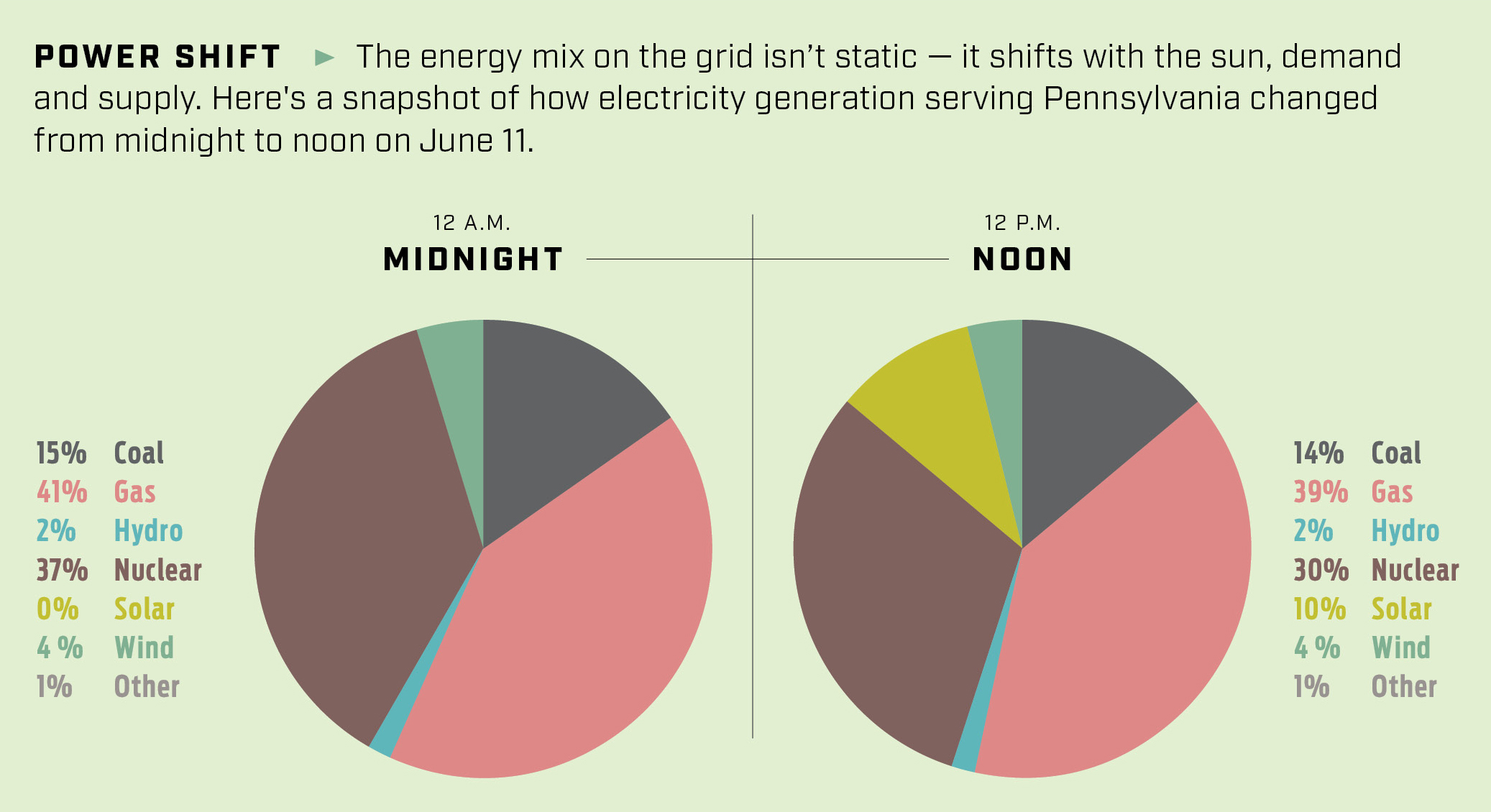

Electrification, à la Hamilton and Salkie, is catching on. But the International Energy Agency cautions that for electrification to make any dent in global carbon dioxide emissions, energy generation needs to shift to low-carbon sources. Think about it: if you buy electricity from a gas power plant, then your carbon footprint is about the same as if you had burned the gas in your kitchen. So, how do we know where our energy is coming from? And what can we do about it?

Unfortunately, whether you buy energy from PECO or a renewables-only provider, you can never control which generation sources you’re tapping, due to the complexities of the system we call “the grid.” But this doesn’t mean that consumers are helpless when it comes to choosing power sources. Far from it.

We are now completely electric.”

— Jen Hamilton, homeowner

Hamilton and Salkie installed solar panels on their roof in 2017. On sunny days, the panels generate enough electricity to charge their Tesla Model S, an electric motorcycle and their electric bikes — and keep their lights and appliances on. But since some days aren’t sunny, they also purchase electricity from a company that deals only in renewables and buys surplus solar energy from customers.

Hamilton is under no illusions about what happens when she buys “clean energy” from this provider. “It’s not like the individual electrons are tagged and they find their way from the wind generator,” she says. Rather, “they put that much energy into the grid, we draw that much energy from the grid and bookkeeping happens.”

The bookkeeping happens via renewable energy certificates, or RECs. When a renewable energy supplier generates one megawatt-hour of electricity and delivers it to the grid, they are issued one REC with a trackable serial number. They can then sell that REC in an open market, enabling customers to claim ownership of that amount of renewable energy — regardless of where the electricity in their power lines actually comes from. Utilities like PECO use RECs to show that they’re meeting the state mandate to have 8% of their power supply come from renewable energy sources.

The REC market, however, is separate from the wholesale energy market. Here in the Mid-Atlantic region, energy is traded by a profit-neutral entity called PJM Interconnection. Daniel Lockwood, a member of the corporate communications team at PJM, says that “PJM’s primary responsibility is to keep power flowing 24 hours a day, seven days a week for 67 million people in 13 states and Washington, D.C.” At their headquarters in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, PJM dispatchers monitor the power levels in the high-voltage transmission system.

A video produced by PJM shows the inside of their control room, complete with wall-sized monitors covered in glowing text and meter bars. Operators at desks bearing smaller screens watch the readouts to make sure that, as the demand for power fluctuates, generating stations are putting out enough energy to meet that demand. Dispatchers decide when it’s time for different power plants to “spin up,” and the order of the queue is based on bids — or, how many cents per kilowatt-hour each generator is willing to sell its power for that day.

Certain kinds of power plants will bid very low, to make sure they always stay online. These include plants reliant on technologies that take a long time to ramp up, like nuclear and coal, or sources where the operating costs are very low, like wind. “Actually, wind will bid a negative number,” says Barry Mather, chief engineer in the Power Systems Engineering Center at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Colorado. “Because wind, at least currently, gets production tax credits.”

Other types of power plants — natural gas combustion turbines, for instance — always bid the amount that makes them an acceptable profit. So-called “peaker plants” don’t run very much and are often expensive, but they help out on days of peak demand.

“The typical way a market runs is they just stack them from who bid lowest to who bid the highest, and they go up the list” until the current demand is met, Mather explains through a video chat. “What some people miss is: everybody gets that price.” Once enough generators have come online, the highest of the accepted bids is what everybody gets paid by the distribution providers — your local utilities — who buy the power. About two-thirds of electricity in the United States is sold on this type of market. (And there are more nuances to grid dispatch, especially in response to line congestion or equipment problems.)

Mather’s research group at NREL is designing the next generation of inverters, devices that convert direct current at the generating source into alternating current. The new inverters will reduce the number of transformers — a different electrical device — needed to “step up” the voltage before electricity travels along those tall, long-distance power lines. Reducing the number of transformers needed will help with lingering supply chain issues from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“To me, the industry is at a little bit of an inflection point,” says Mather. “Wind and solar and renewables in general have been the low-cost leader and have been building massive, massive plants everywhere.” Now, with federal subsidies potentially becoming scarce, he says, “we get to see if some of the advantages pencil out without as much support.”

One such renewable energy project is located near Gettysburg, Adams County. In Straban Township, solar arrays dot the rolling farmland. Some families in the area have leased small sections of their land to Adams Solar, LLC, a subsidiary of Energix Renewables. A third-generation farmer named Brian Redding owns two of the 15 parcels that are part of this industrial solar project.

“If you’re any sort of a landowner, you’re constantly being approached by developers,” Redding says over the phone. He sees the lease with Adams Solar as a way to future-proof his farming operation, which can suffer intermittent losses due to crop market volatility. And the small portion of his family’s land currently occupied by solar panels — 70 out of 385 acres — can go back to being farmland after 40 years, which is not the case for other types of development like housing. Plus, the solar company is paying 13 times more in taxes for that land use than Redding’s family was. That money goes into the local government and school.

Other residents of Straban Township don’t have such a positive outlook on the installation. “The vast majority of what I saw in the newspapers wasn’t really valid,” says Redding. “And it did kind of get boring time after time, going to these township meetings, hearing the same thing over and over.” People would complain about solar panels ruining their views or raise questions about water quality, erosion and decommissioning. There was so much opposition that, eventually, Straban and other nearby townships changed their zoning ordinances to severely limit new solar projects.

One recurring complaint was that the energy produced by these solar panels is going to Philadelphia, since the City has a power purchase agreement with Adams Solar that — on paper — now provides 25% of the electricity used by municipal buildings in Philly. “A lot of people thought that they were going to bury a cable from Adams County all the way to Philadelphia,” says Redding. “That’s not true at all.”

Redding’s older brother Doug has an apt metaphor for the grid. “Visualize a lake of electricity,” he says. Generating stations are like springs and streams that feed the lake. Then homes and businesses pump out what they need. But all the resources get pooled together.

Our lake’s capacity, however, is limited by the system we’ve built to contain it. And this is becoming a problem as both the demand for electricity and the desire to build more clean energy generators continue to increase.

When a developer wants to build a new generating station in the PJM service area, they need an interconnection permit to access the grid. Getting a permit requires inspections to ensure that the surrounding infrastructure can handle the additional power. This infrastructure includes long-distance transmission lines as well as substations, where voltage is either stepped up or down as power enters or leaves the grid. And if the infrastructure is already operating at full capacity, the cost of building a new substation falls on the developer.

This may be an expected cost for corporations building industrial-scale projects, but it can be an unpleasant surprise for homeowners who find out that the solar panels they want to put on their house would overload their neighborhood substation. “Most every time, those upgrade costs get passed on to the customer,” says Brandon Woody, a project manager at US Solar. “And those costs can become astronomical quite quickly.”

PJM has been so overwhelmed lately with interconnection requests that they stopped accepting new proposals in 2022 to work through their backlog. Although they’ve been making a dent, many renewable energy developers have needed to withdraw their requests, since lengthy delays can mean that landowner agreements expire or other problems arise. Politico’s E&E News reports that PJM plans to start accepting proposals again in 2026 and thereafter keep the wait times under two years. Rather than using a first-come-first-served approach, the company has started prioritizing “shovel-ready” projects to accelerate the pace of new construction.

But the new projects are not coming online quickly enough for growing demand. “Pennsylvania is on the same electric grid as Virginia, which hosts about a quarter of all data center capacity in the Americas,” write Penn State University professors Hannah Wiseman and Seth Blumsack, who study energy law and electricity markets, in an article for The Conversation. “Rising demand is also driven by the increase in electric vehicles and the replacement of gas- and oil-based furnaces with electric heat pumps.”

And the squeeze is starting to show up in electricity bills across the state, evidenced by a June 1 rate hike. These increased costs are due to both the imbalance in supply and demand, making energy a scarcer resource, and the need for local utilities to continue expanding and upgrading the physical wiring of the electrical system.

Lockwood, the PJM representative, says that PJM’s “key areas of focus” include keeping existing energy resources online as long as possible, reversing the retirement of older power plants that have gone offline and supporting investment in natural gas pipelines. “It’s important to note that PJM remains neutral on energy policy or energy resources,” Lockwood writes. They’re just trying to keep the lights on.

What’s an eco-conscious consumer to do?

Every time you pay an electricity bill, you’re voting for the kind of energy future you want.”

— Zoë Gamble, CleanChoice Energy

The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission allows electricity customers to choose their supplier, meaning you can pick a utility company that buys RECs, as Hamilton and Salkie have done for their Manayunk home. “Every time you pay an electricity bill, you’re voting for the kind of energy future you want,” says Zoë Gamble, president of CleanChoice Energy. But as a recent Grid article explains, the process of shopping for a new provider can involve confusing options and misleading introductory contracts.

Putting solar panels on your house can reduce the net amount of electricity you draw from the grid, but there are tradeoffs. You can either pay high up-front costs to own your panels or essentially lease out your roof space — assuming you can find a solar company that operates in Philadelphia and is able to secure an interconnection permit.

Some states are seeing a rise in community solar projects, where households can pay a subscription fee to support a medium-sized installation that feeds the grid. But Pennsylvania lawmakers have not yet agreed on how to legalize such developments. Apparently, though, there’s a different model that both is legal and bypasses the interconnection queue. Redding leases a small portion of his farm for community energy, in addition to his agreement with Adams Solar. “The energy is consumed within three miles of where it’s produced,” Redding says. “There’s no underground cables. There’s no substations.”

Creative solutions and new technologies will continue to offer hope for a carbon-negative future. But real change requires investment. “From a technical standpoint, it’s completely possible to operate the system however we want,” says Mather, the NREL engineer. “We can operate it with 100% coal if we want. We can operate at 100% renewable if we want. So it’s really a choice for us, as a society. But always the easiest choice is the economic choice.”

And renewable energy can be very economical — in the long run. Hamilton says, “We had to borrow money to put [the solar panels] on the roof, but they paid for themselves in five or six years” through RECs and savings in utility bills. And it sounds like she and Salkie just might keep blazing the trail toward energy independence.

“We keep talking … We’ve got the panels. Do we get the battery?”