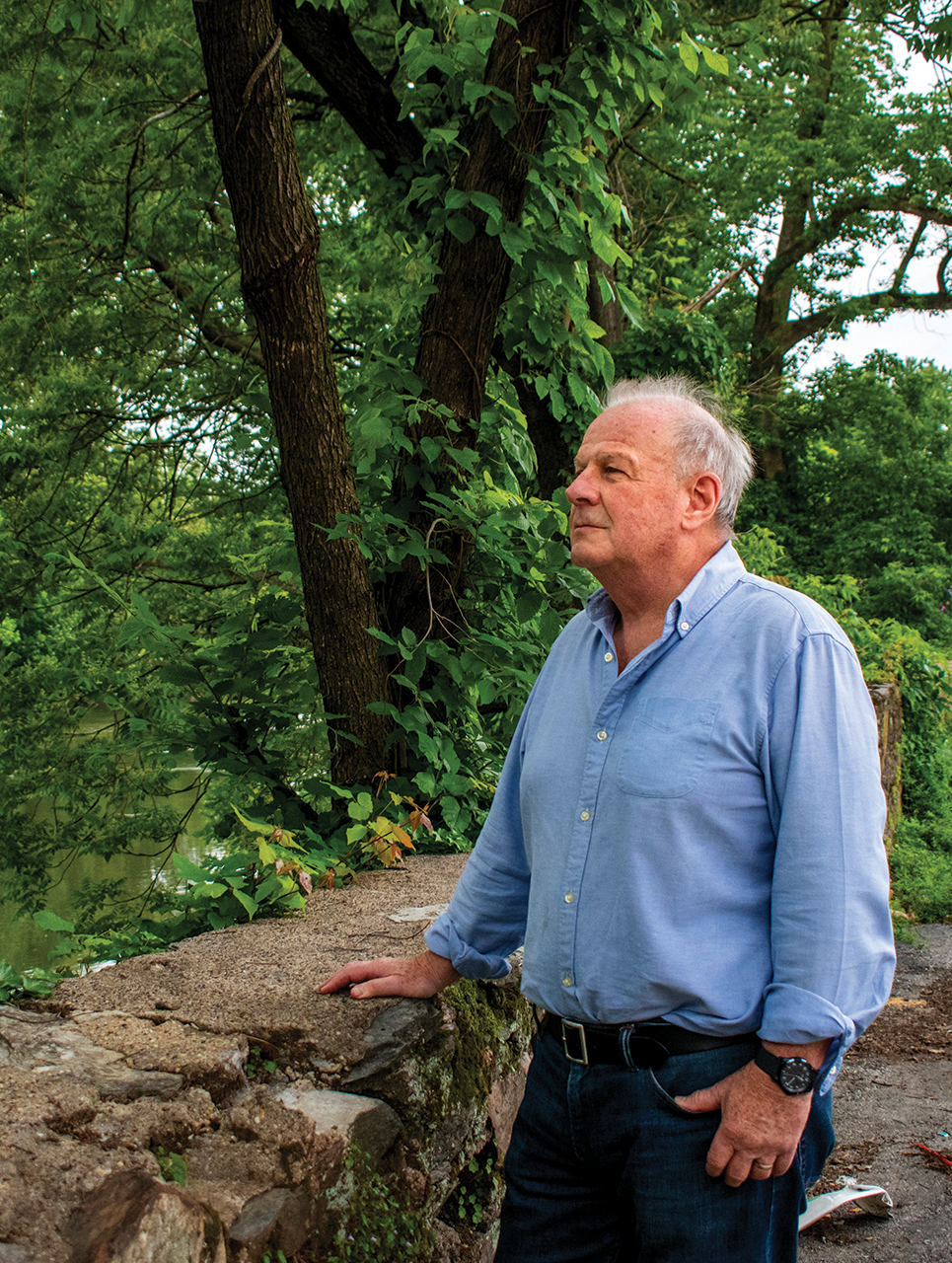

The morning after Hurricane Ida devastated Manayunk in September 2021, John Hunter stood looking over the intersection of Main Street and Shurs Lane, watching floodwaters carry away the back deck of the former Mad River building.

“As the waters were flying by, it got to the point where this bar became detached from its foundations and started to move and float,” says Hunter, zoning chair for Manayunk Neighborhood Council (MNC). “This whole bar just floated down the street.”

Manayunk is one of Philadelphia’s most flood-prone neighborhoods. When the Schuylkill River floods, the adjacent corridor east of Shurs Lane — referred to as lower Main Street — can be engulfed by feet of water, as the floodplain extends as far as Station Street, about halfway between Main and Cresson Streets. And projections show that this corridor has extreme levels of flooding risk over the next 30 years.

Lower Main Street is a conundrum for development. Historically, much of the corridor has been zoned for industrial commercial mixed use, but it hasn’t been reclassified in over a decade, leaving the area “frozen in time,” as Hunter calls it.

“This is perceived as being run-down, neglected, not very attractive,” says Hunter. “And it’s the connection between the city from Kelly Drive to the commercial corridor [of Manayunk]. So there’s an obvious problem.”

For years, MNC members have been pushing to transform the lots between Main Street and the Schuylkill River into a resiliency park. Hunter, an architect and Manayunk resident of 35 years, has been working with zoning in the neighborhood for nearly two decades. He maintains that this corridor is simply unsafe for residential development, as there are no evacuation routes from Main Street for nearly a mile from Shurs Lane to where Main Street meets Ridge Avenue.

“If you build anything here, people can’t get out. They’re stuck,” says Hunter. “The only people that can get in and out are first responders in dinghies. And even they are in danger because there’s all sorts of stuff flowing down the river: trees, dumpsters, all sorts of things.”

It is land which is relatively cheap at the moment to acquire. And it will then have a function which attracts and connects with Kelly Drive and Fairmount Park and the commercial district.”

— John Hunter, Manayunk Neighborhood Council

And yet, residential developments are in progress: the former G.J. Littlewood & Son textile mill at 4045 Main Street is set to be developed into a seven-story apartment building with two floors of parking on the ground levels. The developers appealed for a zoning variance to allow residential use of the site.

At a May 7 zoning hearing addressing the proposed development, Abby Sullivan, chief resilience officer for the City’s Office of Sustainability, stated in public comment that the office is “opposed to variances that bring more residents into the floodplain,” citing “significant risk to life and property.”

In an email to Grid, Sullivan wrote that although she couldn’t comment on specific proposals, a concept like the resiliency park is something the Office of Sustainability would support, as an alternative to “putting homes or businesses in a location with high flood risk.” She called the idea of a park a “common-sense approach,” a phrase also used by Hunter to describe this land use, as it would be compatible with the inevitable flooding.

“It is land which is relatively cheap at the moment to acquire. And it will then have a function which attracts and connects with Kelly Drive and Fairmount Park and the commercial district.”

What Is a Resiliency Park?

Resiliency parks along waterfronts, in addition to providing recreational spaces for pedestrians and cyclists, can accommodate and recover quickly from flooding with minimal cost and disturbance, Hunter says. With flood-resilient design techniques and natural vegetation, such parks can mitigate stormwater and create drainage that reduces the impact of a storm or a flood event.

In July 2024, East Falls Development Corporation and Manayunk Development Corporation published a flood mitigation study that explored strategies like creating a linear park feature along the Schuylkill River. Such a park would “provide a buffer between the river and the neighborhoods, increase floodplain storage, incorporate other mitigation strategies such as berms and bank stabilization, and provide a space designed to flood and recover quickly.”

The study found that a resiliency park would offer multiple benefits to the community and had a high amount of neighborhood support. But it also found that the project would likely require multiple grants and government funding, and that it would take many years for residents to see its flood mitigation benefits.

Hunter believes that the park could be incrementally developed over several years, by acquiring the lots along the river (many of which are vacant) on a piecemeal basis. MNC has been working to apply for grants, in partnership with Manayunk Development Corporation and with the City Planning Commission, to consider the park as a flood-resilient alternative to residential development.

MNC is not alone in supporting the idea of a transformed, flood-resilient riverfront: a group of second-year students from Thomas Jefferson University’s landscape architecture program created designs reimagining three parking lots at 4000 Main Street as a sustainable public nature park. Their projects, which were exhibited in the Manayunk Development Corporation’s welcome center this spring, explored strategies for managing stormwater runoff, enhancing the natural landscape and improving public access to the Schuylkill River. Hunter hopes that this exhibit can help garner more community support for the park.

“I think it would be great if we could somehow muster enough energy to get a grant to piggyback on the mitigation study, and do a resiliency park study that would give people some understanding of what we’re trying to suggest.”

In Hunter’s vision, the park would have a cycle path from Lock Street to the Pencoyd Bridge — a path that would run parallel to the proposed Schuylkill River Trail extension between Venice Island and Kelly Drive. This completed segment would cross the Schuylkill at Venice Island and follow the river on the Montgomery County side before crossing the Pencoyd Bridge back into Manayunk. Hunter says that there is enormous potential for a cycle path along Main Street, which would help direct cyclists away from the dangers of parked cars along the current narrow corridor.

The problem, Hunter says, is that, in the meantime, residential development is more likely to get financial backing than a public park. But there might be a way, Hunter says, for these two visions for lower Main Street to coexist.

On the north side of Main Street, if there were a way to construct flood evacuation routes behind the properties next to the railway, Hunter says residential development could be possible — and these potential units would be more valuable, he argues, as they would overlook a riverfront park.

Although many community members like the idea of the park, without a formal course of action or support from City agencies, it is, Hunter says, “a long, hard road.”

This special section is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This special section is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This is a brilliant idea! The River needs more buffer areas and more green space will be welcome for Manayunk.