The FBI kept Hakim’s Bookstore, 210 S. 52nd Street, under surveillance for some time, sniffing around for subversion, says Yvonne Blake, 70. Daughter of Dawud Hakim, the store’s late founder, Blake recounts how her father had done the unthinkable in 1959 by opening an independent Black bookstore, five years before segregation would be outlawed in the United States.

Given that move, the G-men thought he needed watching.

The FBI’s fears recall the ferment that greeted the nation’s first documented Black bookstore. Abolitionist and businessman David Ruggles (1810-1849), born free in Connecticut, launched his enterprise in 1834, according to the David Ruggles Center for History and Education in Florence, Massachusetts. Ruggles’ establishment, near Broadway in New York City, offered “Anti-Slavery publications of every description…” according to his 1834 newspaper ad.

Ruggles, who withstood beatings, a near-lynching and an attempt to kidnap him into slavery, also sold feminist works. He had a reading room and lending library in an era when New York’s public libraries barred Blacks. Ruggles also helped hundreds of fugitives from slavery, including Frederick Douglass, whom he reportedly hid for several days.

In time, stores like Young’s Book Exchange, begun in 1915 by George Young, a Pullman porter and the son of freedmen, sprang up. Young found it “ … exceedingly gratifying to note the growing interest manifested in books by and pertaining to the Negro race … ” according to a blurb he placed in The New York Age, a Black weekly newspaper published from 1887 to 1953.

Ruggles set a high bar for community service for Black proprietors of independent bookstores. Today, the U.S. has 125 Black-owned bookshops, according to Oprah Daily, with Greater Philadelphia boasting a handful of such businesses.

“When you know your history, you have deep pride in yourself.”

—Lawrence Miles, La Unique African Bookstore & Cultural Center owner

Each seems to have a distinctive flavor—Amalgam Comics and Coffeehouse, in East Kensington, for example, announces its slant in its name while Black and Nobel, in Society Hill, offers health products as well as books—many of the entrepreneurs share community concern and grit. Those qualities have stood them in good stead recently as they did Ruggles 200 years ago.

“My father was passionate about sharing Black history,” says Blake, Hakim’s current owner. “He was an accountant for the City of Philadelphia, but he sold books from the trunk of his car and did people’s income taxes to raise money to start the store. He said that knowing our history strengthens Black people.”

Hakim stocked books like “The Five Negro Presidents” (1965) by Jamaican-American journalist J. A. Rogers (1880-1966) and “They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America” by linguist and anthropologist Ivan Van Sertima (1935-2009). Hakim’s inventory also included journalist John Howard Griffin (1920-1980), author of “Black Like Me,” (1961), a nonfiction account of a white man who took a drug to darken his skin so he could experience life as a Black man in the South.

“We still stock those books,” Blake says.

Hakim passed down knowledge in other ways, too.

“I got my first book here in 1974,” recalls long-time customer Jerry Williams, 60. “It was ‘Malcolm X Speaks’ (1965) for 60 cents. Instead of hanging out on the street, a bunch of [guys] would come here and … [Mr. Hakim] would talk with us. If we didn’t have enough money for a book, he’d give it to us, then quiz us about it later.”

Nowadays, Hakim’s still offers biographies, books about healthcare and spirituality, as well as figurines, puzzles, tote bags, beaded jewelry and other African-themed gifts, but it has honed in more on young people.

“We’ve expanded the children’s section,” says Blake, who, like her sister Glenda, has worked in the store since her high school days. “Our children must know what we’ve accomplished. I didn’t learn about the wealth accumulated by ‘Black Wall Street’ and the 1921 [Tulsa race] massacre that destroyed it until I was grown. Our children must know what we achieved.”

FBI surveillance eventually ended, but the bookstore has faced other crises.

In 1997, Hakim died.

“I was working full-time then,” says Blake, retired now. “I would rush home from work, catch a nap, then open the store. Other family members pitched in, and they do so now even more, but those were grueling days.”

More challenges loomed in 2020. The pandemic almost shuttered the store, Blake says. “I filled some orders from home. Then, after George Floyd’s murder some people were marching [in solidarity with Minnesota protestors], and some were looting. Most of the looting took place between Market and Walnut [streets], just north of us. The National Guard was stationed at Market Street. We locked up that Sunday [May 31], and a young man, a volunteer, stood guard in front of the store all night.”

Then sales surged.

“Customers of all colors, including many new white patrons, couldn’t get enough books about Black history,” Blake says. “Books flew off the shelves.”

Things have settled into a steadier rhythm for Blake and her staff, with demand higher than pre-pandemic days.

“This has always been a family enterprise,” she says. “My sister, daughter, granddaughter and grandson work here. We promised [Hakim] to keep his legacy alive, and we’re doing it.”

In another corner of Philadelphia Jeannine A. Cook, 38, defied doomsayers when she opened Harriett’s, a feminist bookstore on Girard Avenue in Fishtown. Friends warned that she was courting racist violence in that area.

In time, that threat did come, but like the store’s namesake—Underground Railroad conductor and Union Army spy Harriet Tubman (1822-1913)—Cook followed her instincts and opened for business in late January 2020.

Strapped for cash at the outset, Cook cobbled together bookshelves from pipes and other found items, and plumped up her inventory with volumes from her personal library.

“It hurt to take those books from home, but I kept asking myself, ‘How serious are you about this bookstore?’ then I’d bring them in,” she remembers.

Harriett’s has books that celebrate Black women artists, authors and activists. Fiction by Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, science fiction superstar Octavia E. Butler and Harlem Renaissance luminary Zora Neale Hurston fill the shelves. Some titles sizzle, like 2020’s “Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals” by Saidiya Hartman.

Hardly had Cook opened her doors when COVID-19 shut them—but not for long.

“We moved the bookstore out to the sidewalk,” she says, “the shelves, books, furniture, everything. People said the furniture would get broken and rained on, and it did. But we know the healing properties of reading, so we just kept going. Young people have the energy to do that work,” Cook says of her cadre of teen and twenty-something volunteers.

Cook used the sidewalk for more than selling books.

“I had the young folks stand on a soapbox inside the store, practice reciting poetry, then do it outside,” she says. The spoken-word performances helped sell books, but “the young people also conquered their fear of public speaking,” says Cook, who has three paid interns learning the book selling business. “We’ve got to prepare our young people to lead.”

Oprah Winfrey heard about the sidewalk sale and gave her a shoutout, Cook says.

Then an acid test came with George Floyd’s murder.

“We didn’t board up Harriett’s,” says Cook, who flew to Minneapolis to pay homage to Floyd and his family. White vigilantes attacked people protesting in Fishtown, but left Harriett’s unscathed.

“Black and white neighbors stood in front of the bookstore to protect it. They see Harriett’s as a community resource, which it is,” Cook says.

“Bookstores have become more important than ever because so many schools don’t have libraries,” says Cook, who majored in education and minored in communication at University of the Arts.

Cook’s children’s room has child-sized furniture and titles like “Happy to be Nappy,” by the late feminist and social activist bell hooks. Cook also carries “The 1619 Project, Born on the Water,” by Nikole Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson, which explains slavery in U.S. history.

Cook herself read from early childhood and circumstances ingrained the habit.

“My mother, who’s from Trinidad, was a librarian,” she says. “She went blind when I was 10. My two sisters and I—I was the middle one—would read to her. When you have a parent who’s differently-abled, it makes you resourceful.”

Harriett’s packed ’em in wall-to-wall when Will Smith visited in November to launch his memoir, “Will.” Business has gone so well that Cook has opened another store, Ida’s Bookshop, in Collingswood, New Jersey, named for Black investigative journalist Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), who started toting a gun after receiving death threats because of her articles on lynching.

“I’m going to keep following my intuition,” Cook says, “doing what I feel called to do.”

BOOKED UP

Philly boasts its share of indie Black bookstores, and Germantown is home to three of them

At Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books, opened in 2017 at 5445 Germantown Avenue, owner Marc Lamont Hill offers “cool people, dope books, and great coffee.” ⎬ unclebobbies.com

Newly opened Umoja House, 6338 Germantown Avenue, reflects the Ghanian heritage of its owner. Umoja House carries books like Will Smith’s memoir, works on Black history and on West African-based religions. It also offers Nigerian jewelry, other Black and African-themed gifts and Ethiopian coffee in its small café. ⎬ umojabooks.com

Books & Stuff owner Lynn Washington used to sell books “on weekends at flea markets and bazaars,” she says. Tired of lugging books around, she opened a shop on Maplewood Mall [off Germantown Avenue] in 2014. “… The shop [was] an extension of my 28 years working at the Free Library of Philadelphia as a graphic designer.” Washington aims to promote “the importance of reading, particularly for children. I sell books with multicultural, Afro-centric characters and themes, and I emphasize the importance of a home library.”

Books & Stuff went exclusively online in 2019 due to overhead and construction on Maplewood Mall. “Because books are often an expense that many families can’t afford, I try to pass on more of my discount to the customer.”

Washington offers “Surprise Packages.” “Customers pick a price point, $15, $25 or $35. They pick a children’s, teen or adult package [then] tell me a … bit about the recipient’s reading interests, and I put together a selection of books and stuff that I feel will … interest the recipient.” Washington also orders specific books for individuals and groups.

She’s scored a couple of coups. “I’m the exclusive vendor of ‘Philadelphia Jazz Stories Illustrated,’ a book I designed for the Philadelphia Jazz Project. Last year, I was the first book vendor at the Philadelphia Flower Show and I’m going to return this year. I will continue working to get books into the hands of all!” ⎬ booksandstuff.info

Photograph of Books & Stuff Courtesy of Linette Kielinski

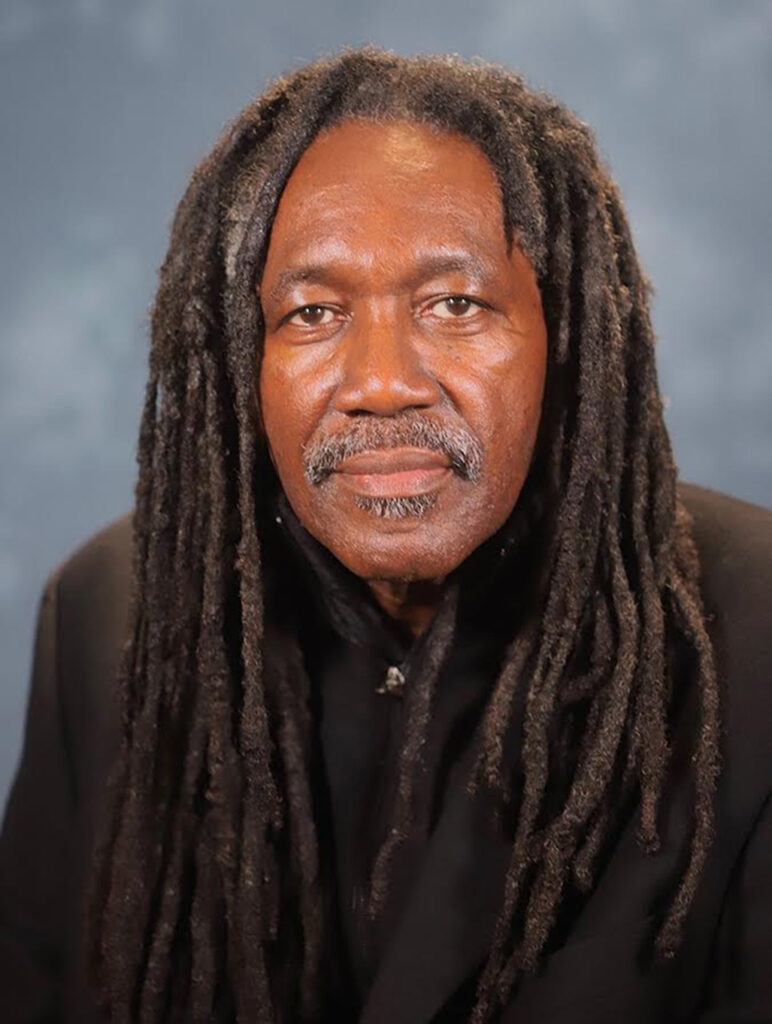

Across the river, Camden’s La Unique African Bookstore & Cultural Center lives up to its name.

Founder and proprietor Lawrence Miles, 88, a U.S. army veteran and former owner of a travel agency, opened the bookstore in 1991 with children’s books.

“When I went to school we studied Negro history,” says Miles, a great-grandfather raised in Crisfield, southernmost town in Maryland. “That’s what our teachers called it. We knew about J. A. Rogers and Carter G. Woodson [founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History as well as Negro History Week, the precursor of Black History Month]. When you know your history, you have deep pride in yourself.”

La Unique—whose “La” comes from Miles’s first name—has books like Renée Watson’s “Piecing Me Together” (2017), a novel about a determined Black girl in a tough world, and Angie Thomas’ “The Hate U Give,” a 2017 novel that became a movie, about a girl’s response after the police kill her friend.

“This location is on the corridor of the University District,” Miles says, referencing the neighborhood that houses Rutgers University. “It’s near K-12 schools in this area. Parents won’t find children’s books [elsewhere in Camden] unless they go to the mall.”

“La Unique” has broadened its stock in recent years to include history, biography and other books for adults. Visitors can browse mysteries by Walter Mosely, works by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and books like “Getting Away with Murder: The True Story of the Emmett Till Case,” by Chris Crowe (2003), which recounts the 14-year old boy’s lynching, which helped ignite the civil rights movement.

“You can find books on health, religion and travel,” Miles says. “If you read a book, you can travel the world from your sofa.”

When you open [Harriet Tubman’s biography] you can hear the voice of an ancestor.”

—Jeannine A. Cook, owner of Harriett’s Bookshop and Ida’s Bookshop

History stands at the heart of La Unique’s offerings. Cowrie shell bracelets, necklaces and earrings for sale recall the use of the shells as currency in West Africa centuries ago. Cloth pocketbooks, CDs and shea butter form part of the attractive displays.

La Unique features a small museum with African sculptures, carvings and drums against a background of mud cloth in black, tan and white, a tradition with roots in 12th-century Mali.

“The museum complements the books,” Miles says. “You can read about African cultures and then see the objects pictured there. I have artifacts from Senegal, Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon, including a 600-year-old bronze statue. There’s a shield from Ethiopia made with an elephant’s ear. Visitors can admire the ability and craftsmanship of Africans. It’s great for kids.”

La Unique also has a 40-seat auditorium called the Poets Den.

“Omar Tyree [a best-selling urban fiction author] gave readings here,” Miles says. “Philadelphia jazz musicians used to jam here.”

The pandemic slammed the door on those events and slashed sales.

“It’s been rough,” Miles says. “Online stores had already cut into my sales, then the lockdown came along. Foot traffic hasn’t risen again, which means less money to replenish stock. I’ve had to refinance the mortgage.”

Miles has a GoFundMe to raise $20,000 for repairs.

Yet La Unique remains a beloved spot.

“This bookstore is a Camden institution,” says Ed Bass, 51, a customer for 20 years. “It adds to the multicultural riches of the city. Mr. Miles is one of the old warriors.”

So much happens at independent Black bookshops that Cook calls them “literary sanctuaries.” At these stores, Black folks can gain self-knowledge denied to them in school, see the skills of African artisans, learn through author presentations and cultural events, and simply find peace. The stores may also groom young leaders. And something more.

“When you open this book,” Cook says, pointing to Harriet Tubman’s biography, “you can hear the voice of an ancestor.”

After George Floyd’s killing, the importance of Black bookstores jumped beyond their surrounding communities. White people began turning to them for guidance.

“I got a note from a 71-year-old white woman who said she’d had white privilege all her life, and now she wanted to learn what was really going on in the country,” says Blake. “She wanted me to suggest books for her to read.”

It was more than a local phenomenon.

“When we reopened … we noticed that the traffic that we were seeing definitely had more white customers coming into Southeast D.C. to shop our store,” said Derrick Young, co-owner of Mahogany Books in Washington, D.C., on an NPR program in May 2021.

“ … My customers were mostly white [after George Floyd’s killing],” VaLinda Miller, owner of Turning Page Bookshop in Goose Creek, South Carolina, said on the same broadcast. But the store had an even greater reach. “I got so many [orders from] people in Brazil and Venezuela,” Miller added.

Blake agrees.

“For the first time ever, I’ve had book orders from Dublin, Guam and the U.K.,” she says.

With their new customer demographics, Black bookstores seem poised to help shepherd the world toward racial justice.

“My father would be so pleased,” Blake says.