story by dan pohlig | illustration by kirsten harperMy first, and unfortunate, attempt at composting was using a static pile. The stinking, hot pile of primordial ooze I created was not only unfit for fertilizing my vegetables, but caused a severe rift in my relationship with my neighbors. So, I decided to switch to another method I’d discovered in my composting research: vermicomposting, or the use of worms to break down organic material.

story by dan pohlig | illustration by kirsten harperMy first, and unfortunate, attempt at composting was using a static pile. The stinking, hot pile of primordial ooze I created was not only unfit for fertilizing my vegetables, but caused a severe rift in my relationship with my neighbors. So, I decided to switch to another method I’d discovered in my composting research: vermicomposting, or the use of worms to break down organic material.

This seemed perfect. Drill some holes in a box. Put some shredded newspapers in the bottom and food scraps on top. Add red worms. Voilà! Fertilizer. No work, no bad smells and it could be kept inside. Just about any box or bucket will work, but I wanted the most organic, least chemical-laden container for my army of garbage disposers. Since I lack carpentry skills (I chose to take ancient Greek in high school instead of wood shop,) I knew I wouldn’t be building the new home for my worms.

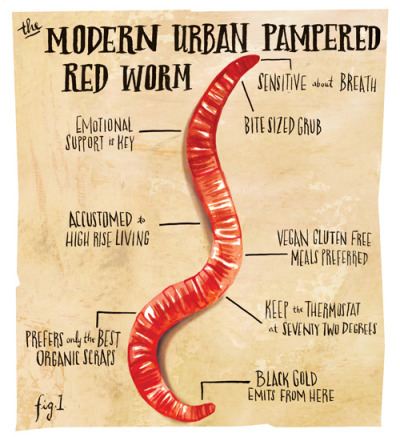

After I searched for “wood worm bin” and made a few mouse clicks, my four-tiered, untreated-wood, worm high-rise was on its way—along with a quarter-pound of worms. A week later, my wife was taking pictures of me with the worms like we had just returned from the hospital with our firstborn.

And just as I fear might be the fate of our eventual offspring, the worms went to live in our basement.

Worms don’t like onions, garlic, too much citrus, meat, dairy or bread, so we’re basically raising vegan, gluten-free worms who are sensitive about their breath. Fortunately, my vegetarian wife handles all our non-Reese’s-related food shopping. and our diet consists mostly of worm-friendly foods.

I won’t say vermicomposting has been effortless, but the extra work I’ve put in has come from not trusting the worms to get the job done. I worried the food pieces were too big, so I began blending them into a slurry and straining out the liquid content. I was spending more time preparing their food than I was our cats’. (In fairness, though, castings—or worm poop—help things grow while cat poop gives me an idea of what an apocalypse would be like.)

Despite some early mistakes, the worms have multiplied from the original quarter-pound to about a pound and a half. Once I found the right balance of keeping the bin moist and the food supply steady, the worms stopped trying to make a run for it and spared themselves the indignity of becoming dried, twig-like carcasses on the tile floor. A fruit fly invasion earlier this summer sent the worm bin to summer camp in the backyard, but with winter approaching they’ll soon be back in the basement. We’ve since learned that microwaving or freezing the food scraps and covering them with more bedding helps prevent future fruit fly populations.

Most importantly, I learned patience is key. Given enough time, the worms will eat the food, no matter how big the pieces. Red worms like to travel up to find food, so I now have two tiers of bins separated by a wire mesh. Searching for the food and bedding in the top tier, the worms have been migrating for the past three weeks, leaving behind their nutrient-rich, brown gold for me to harvest. All this comes just in time for the garden’s winter slumber. The worms and I peaked just a little too late.

In the meantime, the compost will be added to houseplants and a butterfly bush and with luck, will help a young tree survive the winter. But with these valuable rookie-year lessons and some more off season training, we’ll be ready when spring planting comes around. We’re looking forward to big tomatoes in 2012.

Dan Pohlig is a political consultant in Center City and is an active member of the Passyunk Square Civic Association and the South Philly Food Co-op. He lives in South Philadelphia.

A very good illustration and writeup on composting especially since these worms form part of nature and, eventually turn into a natural organic composting machine to help the world’s soil.

A very good illustration and writeup on composting especially since these worms form part of nature and, eventually turn into a natural organic composting machine to help the world’s soil.