The view from Terrence Johnson’s front steps

is surprisingly beautiful. Across the street, towering trees, overgrown bushes and weeds create a vibrant, wild display. The area is one of few in Philadelphia practically untouched by development in the last few decades. ¶ Johnson’s home has been in his family since the 1930s. It sits on a spacious lot just north of 86th Street, only a few blocks from the Regional Rail’s Eastwick stop. Separated from Center City by the Schuylkill River, Eastwick is the southwestern-most neighborhood in Philadelphia located just south of Interstate-95 and the Philadelphia International Airport. Despite being near these major transportation hubs, the neighborhood has a decidedly rural feel. There are only a few other homes on the block, each with their own yard. And just a few streets over is the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, the largest remaining freshwater tidal wetland in the state.

So, last April, Johnson was surprised to see surveyors in his neighborhood. The 128-acre area had been slated for redevelopment in the 1960s, yet had remained relatively untouched since. But, as he soon learned, Korman Residential has maintained their 1961 development rights to the land, and has planned a new $102 million-project for the neighborhood: a 51-building complex with 722 rental apartments. The apartments would occupy 35 acres, while the remaining 93 would be returned to the City for the airport expansion.

While Korman representatives insist residents were notified prior to the surveying, many, like Johnson, say they weren’t made aware of the development plans. In the months following the surveyors’ visit, members of the Eastwick community have risen to action. With support from the Friends of Heinz Refuge, they’ve formed the Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition, organizing meetings and creating a new vision for their neighborhood. They are advocating for the 128 acres to be preserved and added to the Refuge to help transform Eastwick into a green education community.

To the City, the land holds great economic, not educational, opportunity. More residents means an expanded tax base, and Korman estimates that the project would create 590 jobs, although 373 are in construction. But paving over green space, especially one adjacent to the Refuge, could have serious environmental repercussions.

“This is not a ‘not in my backyard’ objection to the development,” says Amy Laura Cahn, an attorney with the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia, which represents the Coalition. “It’s ‘we want to plan the future of our community, and we want do it in a way that reflects the needs of our community and the needs of the environment and the reality of both.’”

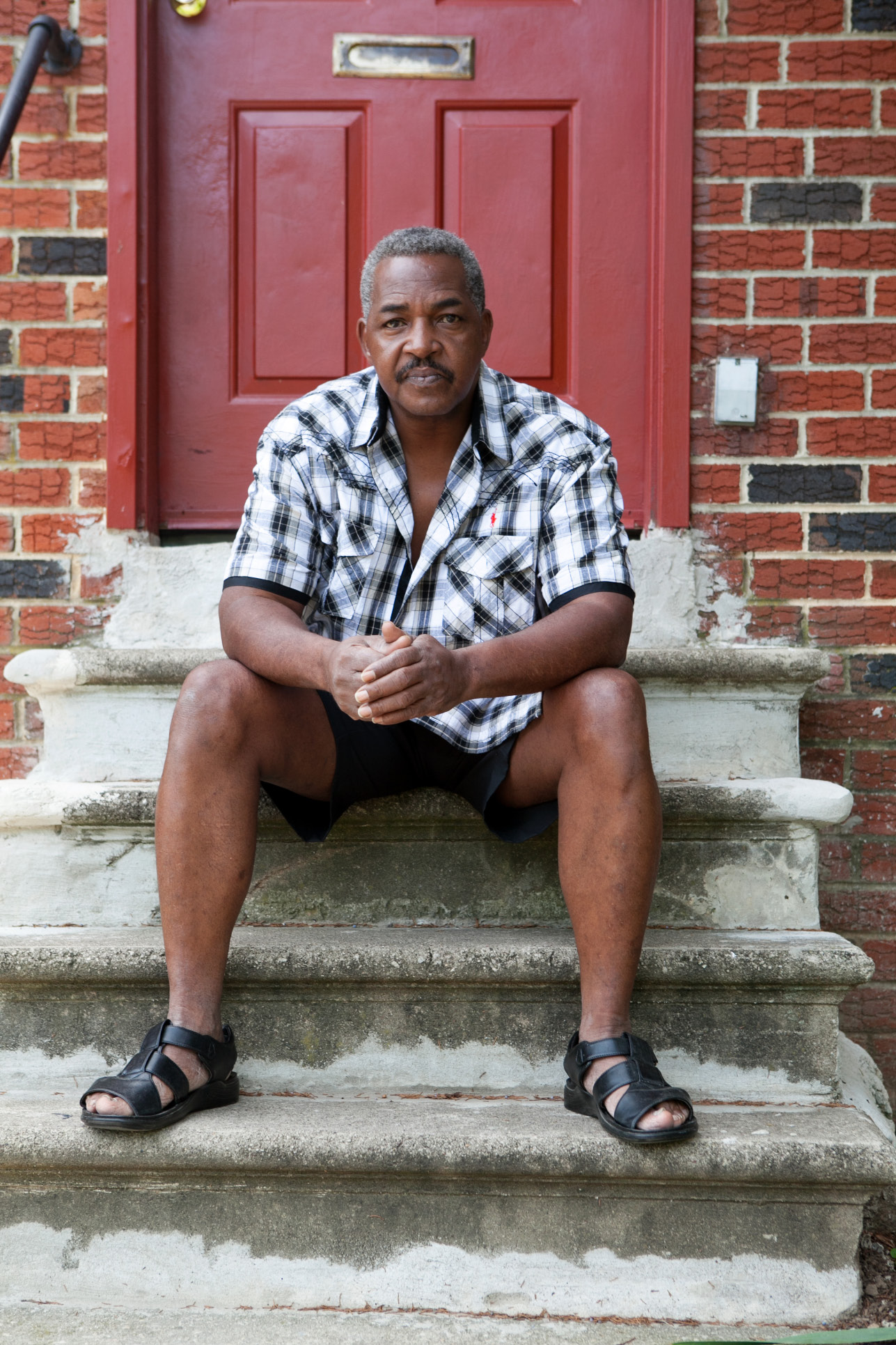

Terrence Johnson sits on the front steps of his home in EastwickThe Meadows

Terrence Johnson sits on the front steps of his home in EastwickThe Meadows

Before the 1950s, Eastwick was a sparsely populated, semirural, working class community. There were open fields, small farms and the occasional housing development; residents, many of which were immigrants, often referred to the area as “the Meadows.” “It was a wonderful community to grow up in,” recalls Johnson, whose family had moved there from Georgia. “You could walk down the street [and] smell fried chicken, Italian foods, kosher pickles. As a kid it was mind-blowing.” For the 1950s, it was an unusually racially integrated community as well.

The neighborhood, which is naturally marshy and prone to flooding, is also on the edge of the city—a location that resulted in fewer city-provided amenities, such as sewers. “[In the 1950s] we still had outhouses in our backyard. We had cesspools,” explains coalition member Pastor Darien Thomas, who was born and still lives in Eastwick.

In 1953, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority announced a $78 million project to make Eastwick the largest urban renewal area in the country. The goals of the redevelopment were to expand the neighborhood’s population, provide jobs and—even though in reality it already existed—create a racially integrated community. There would be industrial and commercial areas, and community and recreational facilities; essentially a “city within a city.” By 1961, Korman Residential had received development rights from the City and began implementing the plan. There was one catch: people already lived where they wanted to develop. The City seized more than 2,000 acres under eminent domain and displaced some 10,000 residents.

“One day you’d see your friend’s family, the next day they’d be gone,” says Johnson. “It created … a lot of tension in the neighborhood.” Neighbors weren’t consulted on the plans and many attempted to stop the development, but were unsuccessful. After homes were built, the developers and the City relied on illegal systems to reach racial housing quotas. For example, white buyers were commonly given immediate move-in dates, while black buyers were told they had to wait a year for housing. Today, the population is predominately black.

Acres of Possibility

Acres of Possibility

In the 1970s, part of Eastwick’s southern end, initially intended for industry and residences, was proposed as a site for I-95. Construction of homes continued, but by the early 1980s it had dropped off significantly. Land, like the 128 acres adjacent to Johnson’s home, which once had homes and businesses, was cleared, but never developed. Today, there is still evidence of the developers’ intentions. A few side roads off 86th Street are named and paved. There are electrical boxes and fire hydrants, yet the roads lead to cul-de-sacs of weeds and dumped tires.

In 2005, the City attempted to reclaim those 128 acres from Korman. A lawsuit followed and Korman successfully defended their development rights, which will expire in 2015. With this date approaching, Korman is eager to bring a new redevelopment project to the neighborhood. However, the land is currently zoned for single-family homes, not apartments. Korman is working with the district’s councilman, Kenyatta Johnson, to apply to City Council for rezoning. The bill was initially proposed on June 12, and included a second bill transferring the development rights of the 93 acres to the City for an airport expansion project. After an extensive hearing where more than 20 individuals spoke out against the project, the bill was denied. A rehearing is expected to happen in early October.

Many residents find the situation reminiscent of the earlier redevelopment initiative. “All of the displacement, [the] breaking up of a very vibrant and viable community, and the stress that it put on the people living there, it would happen again,” says Carol Simmons, an Eastwick resident and member of the Coalition.

For Cahn, the proposal raises the question of why decades-old urban renewal principles are dictating development in 2012. “If the intent of the area is going to change [from single-family homes to apartments], then it should [not] happen with the 1957 planning principles that were used to develop the original plan. The proposed plan does not reflect current planning principles or public policy regarding, for example, early community engagement, sustainable development [and] stormwater management,” says Cahn. “Let’s talk about how we engage in planning in other neighborhoods. How does development happen elsewhere? Does a 50-year-old purchase agreement obviate the need to abide by our current planning principles or policy mandates?”

For Korman, the decision to rezone the land is solely economic. “The single family [home] market has been basically dry in this part of the city—and basically everywhere in the city,” explains Peter Kelsen, the attorney representing Korman. “[Development] can’t be done in the conventional, single-family configuration. There’s just no economic basis for it and no real market for it.”

Korman first approached Councilman Johnson about their plan in February 2012. During the meeting, the Councilman recommended that the developers talk with the Refuge as well as residents about their intentions. “I think how the project probably got off to a bad start is there was some surveying … from the Korman group, which they have the right to do, technically, but some of the community folk got riled up and thought the project was a done deal,” says the Councilman. After that, he continues, there was misinformation on both sides.

Korman disagrees, and insists they’ve been transparent with the community. “[I]t is patently untrue that the residents were not courted,” says Kelsen. “We went to the designated individuals we were told had stakeholder status so that we could begin the informational process.”

When pressed, Kelsen wouldn’t name the specific stakeholders, although he claimed meetings were held as early as March. Residents cite their first meeting as April. Kelsen was equally evasive when City Council asked him during the zoning hearing for evidence of the meetings. In the hearing transcript Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown asks for record of Korman’s meetings with the community, to which Kelsen responded: “I could provide that. I don’t have it immediately but within a few—within a few moments I could give you that.” Kelsen never provided the follow-up information.

Members of the Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition: (left to right) Mariatu Kalokoh, Monique Holland, Debbie Beers and Carol SimmonsKorman’s Second Attempt

Members of the Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition: (left to right) Mariatu Kalokoh, Monique Holland, Debbie Beers and Carol SimmonsKorman’s Second Attempt

Korman’s plan would build 722 apartments and 1,034 parking spaces to accommodate up to 1,000 additional residents. Compared with other apartment complexes Korman has already built in Eastwick, this one would occupy only 20 percent of the land, leaving room for green space. The development would be surrounded by a buffer of trees, and there’s open space designated for a community garden and dog park. The apartments themselves will have a more modern, sustainable design that includes non-VOC paints, energy efficient appliances, and recycled and renewable materials. Although the buffer will be made of native tree species—a solution discussed with the Refuge—the apartments will still share a backyard with current Eastwick residents. Monique Holland lives with her father in one of those homes. “Whatever happens,” she says, “we would be boxed in.”

Residents are also concerned that the new development would exacerbate flooding problems in the area. Eastwick is built on what the Federal Emergency Management Agency identifies as a 100-year floodplain. This means extreme floods have a one percent chance of occurring in any given year; Hurricanes Floyd and Irene both caused massive flooding.

Since Korman is still in the early planning stages, no formal stormwater management plan has been proposed, but Kelsen assures that this is a priority. For a development of this size, “the Water Department has stormwater regulations that kick in, and very specific engineering solutions need to be provided by the developer to make sure there are no negative impacts of stormwater in the area,” explains Gary Jastzrab, executive director at the Philadelphia City Planning Commission. The Water Department is also asking residents to complete a survey that will help determine if flooding is related to city piping or creek overflow. These problems will be further discussed at a hearing with the Water Department on October 9.

Korman has completed traffic and economic studies, but since the project is only in the rezoning phase, no official environmental impact assessments have been done.

An Alternative Plan

The coalition has enlisted the help of 4Ward Planning, a consulting company that considers social, environmental and fiscal interests in development plans, to do their own environmental and economic studies. The sustainable land use planning firm is also helping residents formalize their vision for the 128 acres.

“The goal is to provide an option to City Council to say, ‘Hey, Korman is one option right here on this land, [but] there is a lot more, greater, bigger, broader things that can be done with the whole community of Eastwick,’” says Debbie Beer, secretary for the Coalition. “In our plan, we’ll embrace Mayor Nutter’s pledge to make Philadelphia the greenest city in America.”

The Coalition’s position is bold. “The Korman Development proposal would compound the injustice inflicted on the Eastwick community, opening a new chapter in the shameful history of mistreatment already suffered by the hands of the city,” reads their website.

The Coalition believes the 128 acres, if preserved, could make Eastwick an eco-tourist destination, providing visitors an urban-centric location for hiking, canoeing, fishing and bird watching. “If this area could be protected, this area has huge, huge potential for tourism,” says Gary Stolz, Refuge manager. Each year, the Refuge brings in approximately 140,000 visitors. Stolz believes this number would increase, especially since the Regional Rail has a stop there.

The Refuge was created by the federal government in June 1972 to protect wetland that was proposed for I-95 construction. Located on the Atlantic Flyway, migratory birds use the Refuge as a stopover. The state-endangered, coastal plain leopard frog makes its home in the protected area. The tidal marsh offers flood protection, “filtering toxins and pollutants from our drinking water,” says Stolz. “This is a nursery ground for the Delaware Bay, supporting millions of fish, shrimp, crab and oysters…as well as multimillion [dollar] fishing and recreation industries. The water that flows from here [the Tinicum Marsh] into the Delaware Bay Estuary, is one of the richest ecosystems in the world. It’s a lifeline.”

Environmental education and wildlife-based recreation are important parts of the Refuge as well, and it’s this work that the Coalition feels could be expanded if the 128 acres are left untouched.

Stolz agrees. “It would be phenomenal to provide this benefit for the school kids of Philadelphia, where they could come by mass transit (saving limited school budgets) to the doorstep of their federal public lands,” he says. Stolz has already had several meetings with Korman and has taken the Councilman on a tour of the Refuge. If the development goes forward, there’s talk of adding a path from the train station through the apartment area to the adjacent Refuge. Meanwhile, the Coalition is moving forward with their plan. They’re working to use Pepper Middle School, which is scheduled to close in 2016, as a hub for environmental education.

And then there’s the additional 93 acres, which, if the second bill passes, will be returned to the City for expansion of the Airport. “It could be development associated with the Airport, it could be additional parking, it could be green space that the city maintains for the future,” says Jastzrab. “But there’s no specific reuse of that land being proposed at this time, at least to my knowledge, just for land banking.” Also under threat from the Airport is The Eastwick Community Garden, which has been in operation for more than 40 years. The garden is now in a year-to-year lease agreement with the City. The likely construction plan for the garden: a parking lot.

An Uncertain Future

For the residents, there are still many unanswered questions. “We don’t understand the environmental impacts, we don’t understand the impact on flooding,” says Cahn. “We don’t know what Korman is going to dig up [during construction]. The whole area is filled with river dredge spoils or silt and cinder of unknown environmental quality. What’s going to be unearthed when that starts getting dug up and becoming runoff?”

Cahn’s questions haven’t gone unheard and both the Councilman and Korman have promised better communication in the future. “There will be extensive community outreach,” says Kelsen, “but I’m not prepared to discuss that publicly at this point.”

For Councilman Johnson community involvement is important, but economics are as well. “I always take strongly into consideration the needs and concerns of the immediate communities,” he says. “However, with this particular project, the development will definitely expand our tax base.” Korman is proposing development that won’t require any additional assistance from the City, which makes it especially appealing and viable. “It’s not often you have an opportunity to do development projects in this particular economic climate,” says the Councilman. “It’s very rare.”

The projected economic impacts of the development are impressive. Korman has estimated more than $2 million will be collected in tax revenue. They claim to be interested in working with the community, and wants to address their development-related concerns through a community benefits agreement.

But in response to the Coalition’s vision, Kelsen is blunt. “With all due respect to my friends at the Coalition and to the Friends [of the Refuge] and residents who would like this to be permanent open space, they should work with the City of Philadelphia to find appropriate funding and compensate the developer for it,” he explains. However, Kelsen is suggesting an option that doesn’t seem to be on the table. “That’s not going to happen,” he says, “because no one is going to have the resources in today’s world to acquire this for additional Refuge space. It’s just the reality of the world.”

Despite this, the community isn’t backing down. “I believe that this area represents an incredible opportunity for this city,” says resident Terrence Johnson. “[The Councilman] doesn’t have a clue. He’s going to have a significant fight on his hands.”

For more information on the Coalition and upcoming hearings in October, visit eastwickfriends.wordpress.com

What a delightful, comprehensive overview of the opportunity being presented to the residents and businesses of Eastwick and Southwest Philadelphia!

Hope all the Eastwick community is geared to voice their views to our elected officials – either in person at the City Council hearing on the re-zoning question on October 9 or by mail or email.

Ted Behr

Publisher

Southwest Globe Times.

What a delightful, comprehensive overview of the opportunity being presented to the residents and businesses of Eastwick and Southwest Philadelphia!

Hope all the Eastwick community is geared to voice their views to our elected officials – either in person at the City Council hearing on the re-zoning question on October 9 or by mail or email.

Ted Behr

Publisher

Southwest Globe Times.