A version of this story originally appeared in Hidden City in 2024 and is shared courtesy of that publication.

For nearly two centuries, humans and Mother Nature have tangoed on League Island, the most southeasterly expanse of land in Philadelphia, known today as the Navy Yard. For the most part, humans have gotten the better of it. Over the centuries, engineers, sailors and industrialists turned what was once a low-lying island at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers into a 1,500-acre piece of modern urbanity, replete with giant shipyards and commerce of all types. But as the Navy Yard moves into its next chapter of human habitation — residential living — does it risk the tides turning in favor of Mother Nature?

This is a question that is swiftly moving beyond the theoretical and into the practical. In 2023, vertical construction began on two large apartment buildings at the Navy Yard, with a combined 614 units. With the projects on schedule for a late 2025 opening, by the end of this year the area will see its first civilian residents in historical memory.

The projects’ proponents say that’s a great development. After the City largely assumed ownership of League Island from the U.S. Navy in 2000, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) assumed responsibility for its redevelopment. Early master planning was successfully executed: the Navy Yard now houses “15,000 employees and 150 employers who occupy 8 million square feet” across a variety of commercial enterprises, according to its website.

But what has been missing, its development team says, is residential. Due to a smaller, continued presence of the U.S. Navy, as well as a deed restriction, residential development was forbidden until just the past few years. Real estate development firms Ensemble and Mosaic were selected to bring it to fruition in 2019, and in 2023 the residential deed restriction was lifted, clearing the way for a groundbreaking in the fall of that year.

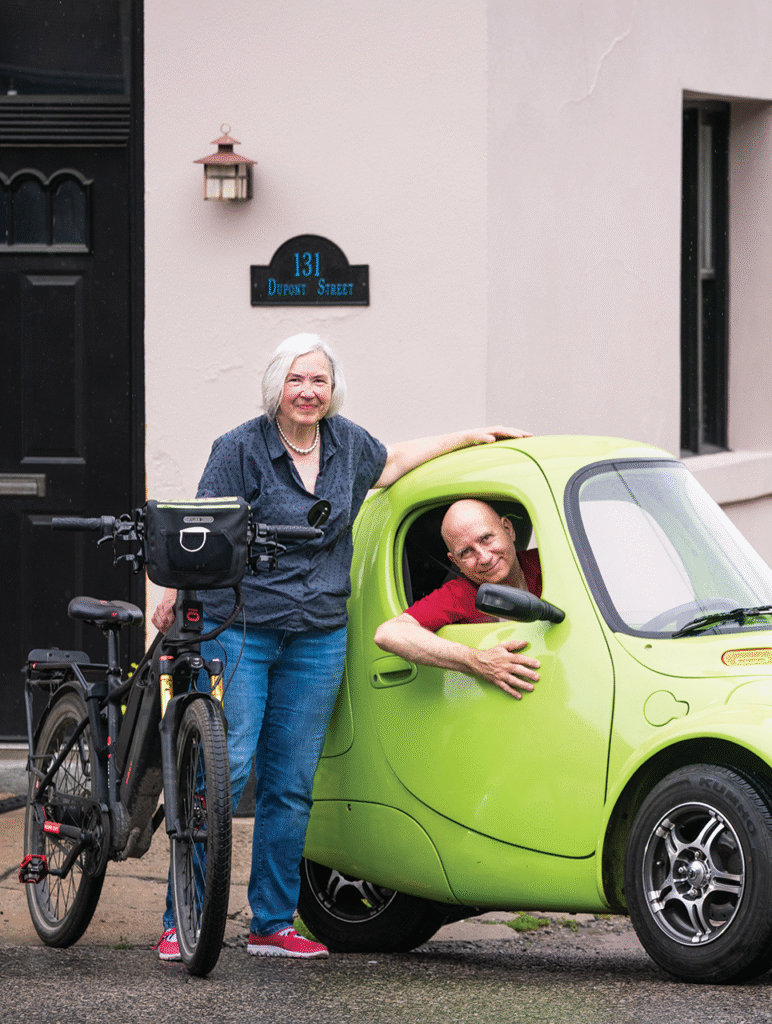

Jeffrey Brown, director of development for Korman Properties, the sub-development firm constructing and managing the new buildings, views his firm as an integral part of the Navy Yard’s ongoing revitalization. Korman’s vision, aligned with PIDC’s, is one of a thriving urban neighborhood where residents can live in close proximity to their places of work, as well as nearby commercial, cultural and recreational amenities.

This was an opportunity for us to really create a new neighborhood for the first time in a generation.”

— Jeffrey Brown, Korman Properties

“This was an opportunity for us to really create a new neighborhood for the first time in a generation,” Brown says. “It’s really providing an opportunity for people of a wide variety of demographics, or socioeconomic status, to live, work and play in one place.”

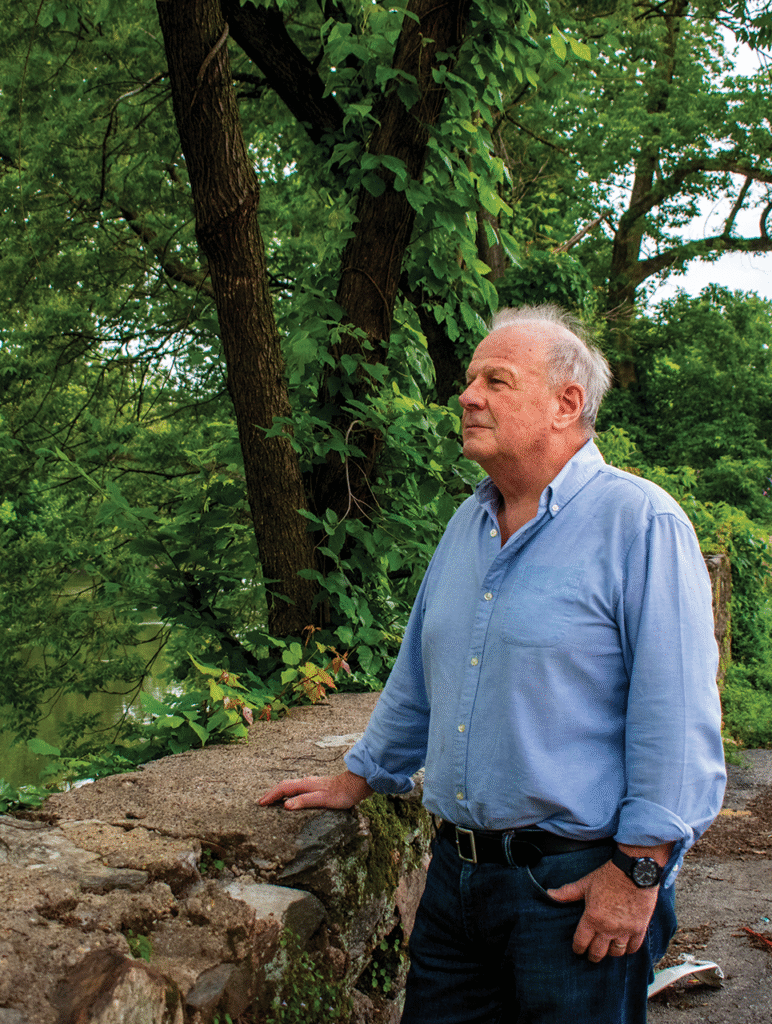

But redevelopment of the Navy Yard is not without opposition. Josh Lippert, a professional floodplain manager and former chair of Philadelphia’s Flood Risk Management Task Force, doesn’t mince words about his concern for residential development at the Navy Yard. Currently, he points out, nearly the entire site exists within the federal government’s designated floodplains. Conditions are expected to only worsen over the coming century as climate change raises sea levels, which, in turn, will push the Delaware River’s tidal waters higher.

Combined with increasingly intense rainfall, as well as the relatively few access points between the Navy Yard and the rest of Philadelphia, the addition of residential units adds significant risk if people become trapped in the buildings by floodwaters, Lippert says. A nine-to-five office use is one thing, but the risk escalates exponentially once people are living on-site and subject to floodwaters rising 24/7, especially as they sleep overnight.

“It’s unsafe. If there is a medical emergency, or any other compounding issue occurring — a fire in the structure — that is going to really increase life safety concerns in those buildings,” Lippert says. “Egress is the biggest issue. There is really only one way out of that site.”

History of an island

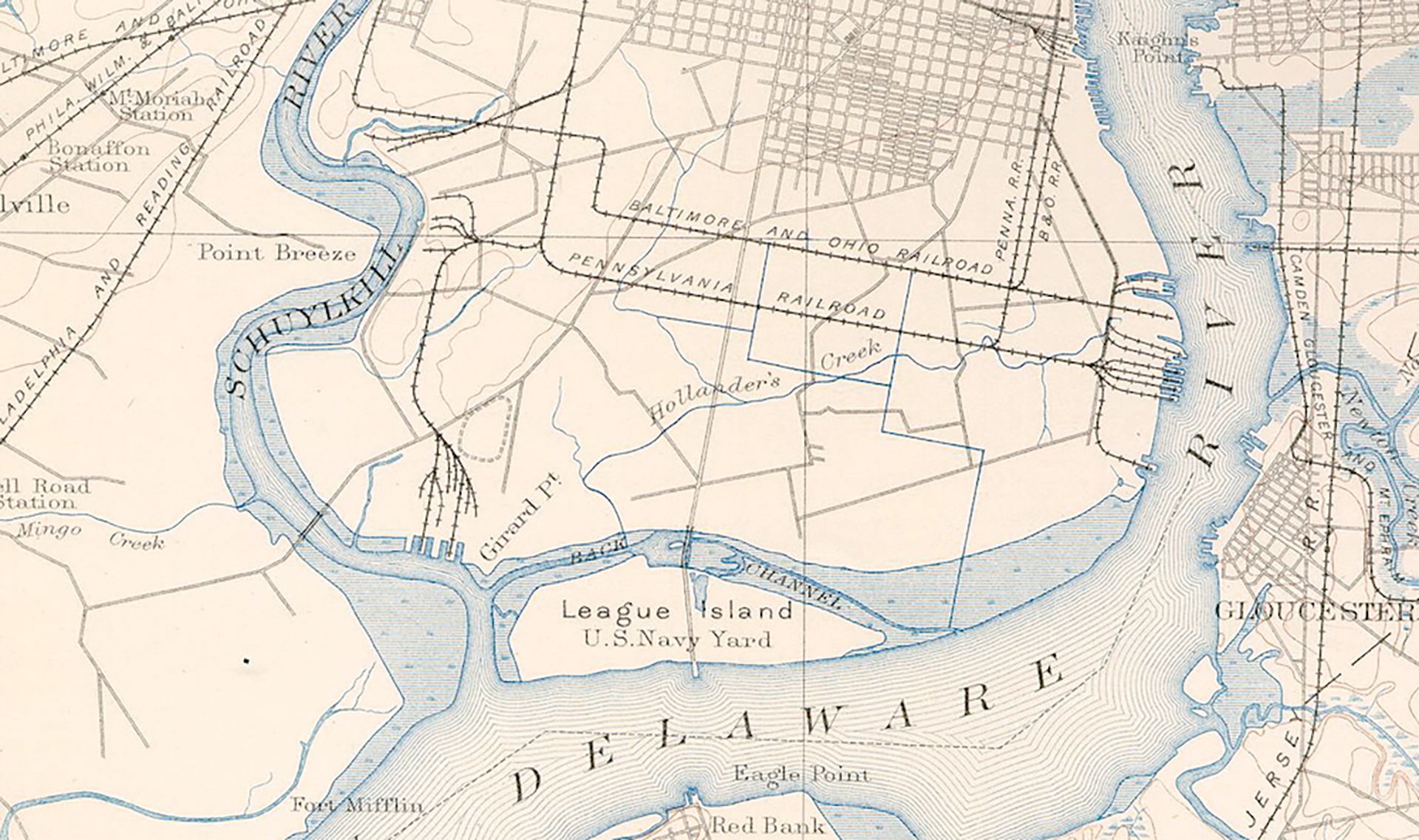

Humans have been eyeing up League Island for some time. According to an 1898 description in The Philadelphia Inquirer, League Island got its name from the eponymous unit of distance, which equates to three miles by land or three-and-a-half nautical miles. Indeed, a satellite measurement of today’s land formation shows a length of just under three miles.

Also according to the article, League Island appeared to originally be attached wholly to what is now Greater Philadelphia before softer soils were eroded by action of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and a channel was formed connecting them, separating a large patch of land from the mainland. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) further notes that League Island was one of just several in the vicinity dating to the Colonial era and earlier and that just offshore from the island were “once sandbars known as the Horseshoe Shoals.”

By the late 1600s, the “peculiarly advantageous position” of League Island was recognized by the land company of London, which built a fort there, the Philadelphia Inquirer piece reported. A century later, in 1783, the island was annexed by Pennsylvania in negotiations with New Jersey, after a delegation from both states agreed to award possession of Delaware River islands based on their proximity to the nearest shoreline.

HSP records that it didn’t take long for development to begin in earnest, in the early 1830s. According to research materials obtained by the organization, “Transcribed and printed letters between Charles Wharton Jr. and Richard Delafield, Captain of U.S. Engineers, and others, concern Wharton’s desire to build a causeway to connect League Island to Philadelphia at Broad Street.”

Wharton, a businessman with interests in the iron industry, wanted to make use of the island for the burgeoning coal trade coming from Pennsylvania’s interior. Delafield approved, explaining to Wharton how he might go about erecting the causeway and piers. Navy Commodore Charles Stewart also approved, HSP noted, as he believed development would also accommodate ice commerce in the winter and provide a safe harbor for ships. Wharton eventually won approval from the state, clearing the way for industrial development.

But the U.S. Navy itself soon had the island in its crosshairs. A brief history featured on the Navy Yard’s website highlights League Island’s role in the “Birthplace of the U.S. Navy,” as a second home for the service in Philadelphia.

“Dating back to the founding of the country in 1776, the Continental Congress leased land along Philadelphia’s Front Street docks to support naval defense,” the article first notes.

By 1794, President George Washington signed the Naval Act to build six frigates for the United States, the first of which was built in a shipyard near Carpenter Street and launched in 1797. That shipyard quickly expanded into an official U.S. Navy facility, the Southwark Yard, which stretched from Federal to Reed streets.

But by the arrival of the Civil War and subsequent ironclad ship technology, the Southwark Yard was in danger of obsolescence compared to piers in Massachusetts and Virginia. The U.S. Navy sought new grounds, and an idea for the Navy Yard at League Island was born. The City purchased the island in 1862 for $310,000, transferred its 923 acres to the U.S. Navy for $1, and construction of a new shipyard began in 1871. Over the next century, 53 warships were constructed and an additional 1,218 were repaired. The land was also further transformed, and League Island became an island no more.

“The eastern portion of the small channel that still separated the island from the mainland was eventually filled in order to make room for a new airfield, Mustin Field, while a western portion of the channel was kept as a reserve basin for ships,” according to HSP.

Yet, by the late 20th century, time was also passing by for the Navy Yard. The last new ship to be built, the Blue Ridge, launched in 1970. A federal decision to close the base arrived in 1991, which officially occurred in 1996, precipitating the City’s redevelopment plans.

Fortified against floods?

League Island has always been a place tied to the water. News reports as far back as 1889 describe storm surges causing the Delaware River to overflow into its meadows. In 1910, a Philadelphia Inquirer piece titled “Storm-swollen rivers invade city streets” described League Island as “practically cut off from the city” for several hours.

“The flood from both rivers widened the back channel and made a broad lake,” the newspaper reported, adding that workers were stranded until the tide went back out.

Egress is the biggest issue. There is really only one way out of that site.”

— Josh Lippert, environmental planning professional

So can residential development really be made to live harmoniously in a place with such close proximity to Philadelphia’s two rivers, in a century when the climate is changing and seas are rising? The Navy Yard’s development team believes so.

A 2022 master plan envisions development of 3,900 total residential units at the site, a significant expansion over prior plans. The two Korman properties, part of the company’s AVE portfolio, are the first to break ground. AVE Normandy, at 1200 Normandy Avenue, will have 267 apartment units, including 100 short-term rentals for corporate clients. A second building, AVE Constitution, at 1225 Constitution Avenue, will have 347 units, including 92 units designated for “mixed income” residents making 60-120% of area median income, says Brown.

Normandy will contain one, two and three-bedroom units, while Constitution will include studios, one and two-bedrooms. Extensive planned amenities include a fitness center, elevated pool deck, lounges, co-working and meeting spaces, bike storage, a café and ground floor commercial spaces.

Brown says Korman believes the $285 million development will have three target customers: white-collar workers already employed at the Navy Yard who want to live where they work, Millennial-aged Philadelphians looking to relocate to a less-dense part of the city with a mix of urban and suburban amenities and retirees from the region looking to downsize.

There are not yet official plans for additional residential development beyond the two buildings, but Brown says Korman remains in talks with the development team and that nothing has been “ruled out” for residential, including the potential for home ownership. But what about flooding?

Kevin Lessard, vice president of marketing communications and government affairs for PIDC, says the corporation “acknowledges the importance of addressing flood risk,” and that the 2022 master plan “includes a comprehensive resilience strategy to address flood risk, climate change and sea level rise.”

“This includes both short- and long-term sustainability initiatives and engineering solutions including elevating the land and infrastructure, incorporating innovative stormwater infrastructure including canals and swales along the streets on the east side of the campus to convey stormwater, and using dry ponds, green roofs and resilient landscaping, coordinating with public safety agencies on emergency preparedness, and regulatory compliance including compliance with building codes and zoning regulation,” explains Lessard.

In a comprehensive 2022 article on the issue, WHYY’s Sophia Schmidt polled numerous regional planners and flooding experts about the proposed safeguards, which also include an early alert system for residents to evacuate and an elevated roadway designed to maintain ingress and egress from the Navy Yard even in the event of four feet of sea level rise. Reviews were mixed, although numerous interviewees stated that it appeared the plans were about as thoughtful as one could hope for when it comes to a parcel of land nearly entirely within federal floodplains. Lippert’s viewpoint stood out as the most critical and remains unchanged.

“The major elephant in the room is that this was an island … and it will once again be water in the future,” Lippert says.

He worries about a future event reminiscent of 1955’s Hurricane Diana, which Lippert calls the last major “catastrophic” event in the Delaware River’s history, having wiped out bridges, industry and other infrastructure along the river. With that kind of destruction a distant memory — indeed a Korman spokesperson noted that the Navy Yard has not experienced a “single significant flooding event” in the past 25 years — Lippert is anxious that developers are underappreciating the risk of what’s to come as sea levels rise and another storm of that magnitude lurks.

His biggest concern is trapped residents. The Korman buildings will elevate residential by leaving the first floor purely commercial. But Lippert likens that to a piecemeal approach that raises properties out of the floodplain one “postage stamp” at a time. As is the case with recently developed residences in other flood prone areas of Philadelphia, like Manayunk’s Venice Island, that can still leave residents stranded within their buildings and potentially requiring rescue.

As the Navy Yard currently only has a few access points to Philadelphia, Lippert worries about the complications of emergency response, especially during a major regional event where power can go down and citywide rescues stretch resources thin. If that did come to pass, he places the greatest amount of responsibility not on the building’s developers, but on the City for what he sees as a lack of forward thinking and present-day regulation on development in at-risk areas.

“We don’t want to think about the future. We don’t think out to 2100,” Lippert says. “There’s no long-range planning because, at the end of the day, it’s four-year political cycles. They want the tax base.”