The table was set, powerful people already gathered round and talking about the future, when Carol Kazeem walked in about 15 minutes late and popped the balloon.

Kazeem, a first-term Pennsylvania state representative from Chester’s 159th district, has had a whirlwind of a year. When the former trauma outreach specialist and 31-year-old mother of three upset incumbent Brian Kirkland for the position last year, despite the Delaware County Democratic Committee and other established political machinery backing him, it signaled political winds shifting in Chester toward more grassroots-oriented leaders.

“It was never going to be easy because this is a machine almost 40 years in, longer than I’ve even been alive,” Kazeem told the Delco Times.

Her fortitude was quickly tested again.

Just a month after her upset in the primary, StateImpact Pennsylvania published a blockbuster story reporting that an energy company called Penn America Energy Holdings LLC had “quietly been shopping plans for a massive liquefied natural gas facility and export terminal in Chester along the Delaware River” to a slew of politicians, including Gov. Tom Wolf, Chester Mayor Thaddeus Kirkland (uncle of Kazeem’s ousted opponent) and other local powerbrokers.

At the same time, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was raging, sending European nations into a panic over the security of both their physical borders and energy supplies. With the majority of the continent’s natural gas previously emanating from Russia, many Europeans were suddenly left to wonder where their next kilowatt-hour was going to come from.

Some industry and political voices posited that the United States, the world’s largest natural gas producer, could act as an energy savior. But only if it exported higher volumes of its copious supplies of natural gas. To do so, the nation would need to build more facilities capable of super-cooling gas to negative 260 degrees Fahrenheit, thus liquifying it for easier transport by ship across the Atlantic.

State Rep. Martina White, Philadelphia’s lone Republican representative to Harrisburg hailing from the far Northeast, was on board. Legislation she introduced — passed by the General Assembly in April 2022 and signed into law by Wolf — created a Philadelphia Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Export Task Force to study the “economic feasibility, financial impact and the security necessities” of siting an LNG export facility in the Delaware Valley.

Now it wasn’t just the U.S. who could help save the day, White argued in a press release, but Pennsylvania “that can make a tremendous difference” with its vast natural gas fields.

In the LNG task force’s first meeting this spring at the Navy Yard, much of the focus wound up outside the meeting room, after longtime Chester-based activist Zulene Mayfield and other opponents were blocked from entering and attracted press attention.

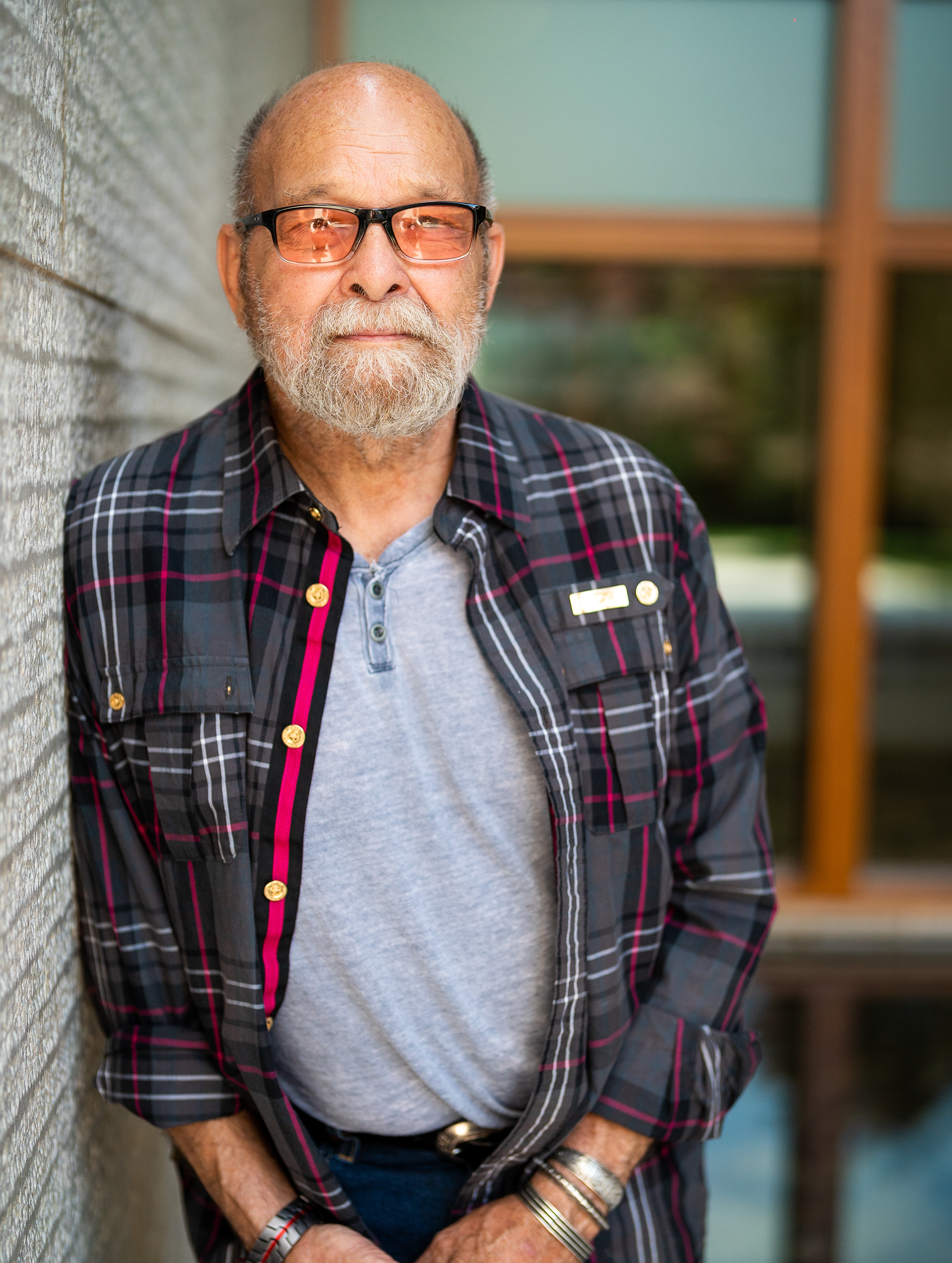

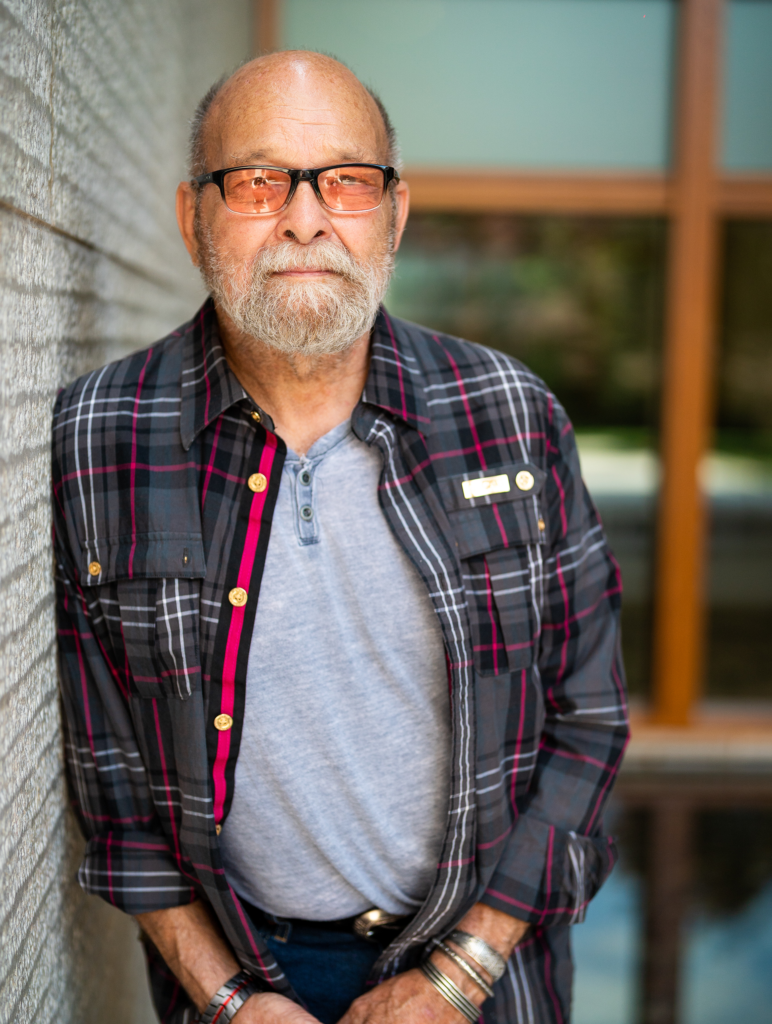

But Kazeem was invited to speak at a second meeting in May at the Steamfitters Local 420 headquarters in the Northeast, White’s home turf. Kazeem was undeterred from offering opposition, citing a long legacy of environmental justice concerns in communities adjoining Chester’s industrial waterfront.

What did we get? A 27% childhood asthma rate, an increase in health risks and illness amongst our seniors, decreasing jobs and companies.”

— Carol Kazeem, Pennsylvania State Representative, 159th District

“What we are witnessing right now is history trying to repeat itself. My community, where I reside with my children, has been promised economic salvation each time an industrial plant is proposed,” Kazeem said, citing local paper milling and trash incineration. “And what did we get? A 27% childhood asthma rate, an increase in health risks and illness amongst our seniors, decreasing jobs and companies.”

Watching Kazeem speak from across the table was task force member Toby Z. Rice. The millennial CEO of EQT Corporation, a Pittsburgh-based energy company, Rice has also had a pretty good run in recent years. A former college baseball player turned natural gas tycoon, Rice and his brothers sold a family-built energy company to EQT for $6.7 billion in 2017, then went ahead and executed a hostile takeover of the company two years later.

The company has since turned record profits and joined the S&P 500 as the country’s largest natural gas producer. Rice has also become a gas evangelist of sorts, spreading the gospel of what American-

produced natural gas supplies could do for the world. This led to profiles in the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal; the former features a picture of Rice sitting at a desk in EQT’s hipster-esque Pittsburgh offices, his white collared shirt unbuttoned, sleeves rolled up, and a neon sign in the backdrop reminding him to “stay shaley.”

But could Rice win over Kazeem?

“First off, love the passion,” Rice told her, smiling. “I think we share something in common. We both want to bring opportunities to this side of the state.”

Rice laid out his best arguments. The burning of coal for energy across the globe is choking the residents of developing nations with particulate matter, he said. Indoors, using wood and other biofuels for cooking is also polluting their lungs. And coal’s carbon emissions are among the worst culprits of climate change. In sum, people all over the globe are gasping for cleaner-burning natural gas.

“Does your community understand we’re not just making LNG, we’re making a product that’s going to help the world?” Rice said.

Kazeem remained unmoved. She had done her homework, she said, and was concerned with the economic uncertainties around future demand for natural gas. She’d prefer for Chester to get some of the white collar industries popping up in wealthier communities, centered around health care. If LNG is so great, why weren’t the Haverfords and Ardmores of the world lining up for a piece of the action? Kazeem wondered.

“I would rather stand for projects that are going to be instrumental moving forward,” Kazeem said. “A project that you can say, ‘I built that, your father built that’ and you can tell your grandchildren that. A legacy that I feel like people want to take on, rather than feeling like you brought something to the community that you will no longer be respected for.”

Up in the air

The unfortunate thing about this debate over the value of LNG exports is that it’s not so simple to score.

In the “opposed” column, a very easy place to start is the essentially consensus understanding among climate experts that if humanity is going to avert the worst outcomes of climate change, we can afford no new coal or gas development. In fact, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change calculates we’re already using enough of these fossil fuels to blow past a critical 1.5 degree Celsius warming target.

Layer on top of that legitimate pollution concerns. Penn America officials have previously issued general promises that “environmental stewardship” would be a top priority for an LNG plant in Chester and told StateImpact that the facility would use electricity instead of on-site gas combustion to power the plant. But the news outlet predicted the facility would still likely emit significant quantities of nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxides, carbon monoxide and particulate matter by comparing it to another proposed liquefaction plant in Northeastern Pennsylvania.

Chester, identified by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection as an environmental justice community due to its high proportion of minority (85% in the census tract of the proposed LNG facility) and impoverished (36%) residents, is already struggling with air pollution from the Covanta waste incinerator, I-95 traffic and other emitting sources.

And at the end of the day, there’s little to suggest an LNG export facility would even live up to its billing as a European energy savior. Experts told Grid that the capacity of an LNG facility along the Delaware River would likely represent a modest fraction of total U.S. exports (the bulk of which emanate from the Gulf Coast) and an even smaller amount of total European energy demand. Further still, the fungibility of international gas markets means LNG loaded onto a tanker on the Delaware River could just as well wind up in Asia, South America and other ports near and far.

“That LNG is free on board which means it can go wherever it wants to,” said Anna Mikulska, a fellow in energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute. “Just take it wherever the price indicates highest profits.”

But even with all of these issues poking holes in the argument for siting an LNG export facility in the region, it’s difficult to completely write off what the Toby Rices of the world are selling.

The operative word is “volatility,” Mikulska says. Geopolitical events have thrown global energy markets into chaos, and the future is uncertain. While European markets are currently stabilized, that’s significantly due to the continent’s wealth, which enabled it to snatch up global gas supplies.

But that kicked severe gas pinches and energy crises further down the economic ladder in countries like Pakistan, Indonesia and Bangladesh, where officials are now freshly thinking about how to ensure energy reliability in the near future. And if gas is seen as too volatile and renewable energy technologies currently too expensive and unreliable, burning coal often becomes the answer.

“We really have seen the return of coal,” Mikulska said, pointing out that even Germany recently dismantled a wind farm to open a new coal mine. “That’s something to consider, particularly in the developing world.”

In this sense, gas becomes a known quantity, with fewer greenhouse gas emissions than coal but with more affordability and plug-and-play reliability than renewables currently provide, especially for cash-strapped nations trying to scratch climate reparations away from their wealthier counterparts.

Ned Rauch-Mannino, president of consulting firm Portsmouth Limited Company and non-resident senior fellow with the Foreign Policy Research Institute, sees value in both increasing U.S. LNG export and the use of renewable energy sources globally.

But at the moment, Rauch-Mannino says, renewables still have trouble with intermittency and meeting peak demand, energy grids are not equipped for rapid adoption of electrification goals and countries of various economic standings are building more LNG import terminals. He wants American-produced gas to meet this demand for both environmental and geopolitical reasons.

“With renewable energy technology like solar panels, we can’t beat competitors’ production costs right now due to standards and labor,” Rauch-Mannino said. “But we do have that energy and high standards advantage to leverage in gas.”

While he also says an LNG export terminal in Southeastern Pennsylvania wouldn’t secure Europe’s energy markets on its own, he still believes it would help someone, somewhere.

“Greater Philadelphia has an opportunity to have a small but meaningful role in advancing broader security,” he said.

And the proposed project is not without local supporters in Chester. Economics are a major part of Penn America’s pitch, with an estimated “4,000-plus jobs during construction,” along with a boost to city tax revenues in perennially cash-strapped Chester. Opponents argue that the majority of jobs would be temporary and permanent ones would mostly go to non–Chester residents.

But Mark Freeman, president of Laborers Local 413, a building trades union headquartered in Chester, told the task force in May he believed construction of an LNG facility would be good for his members, especially following the 2019 closure of the former Philadelphia Energy Solutions oil refinery in South Philadelphia.

“Members have had to take lesser paying jobs, or work two jobs,” Freeman said. “This [proposed LNG] plant brings opportunities for our members to make living wages and to continue to send their children to college.”

Getting real

These are difficult problems to unravel. Where exactly are the lines between idealism, realism and the whole world is at stake so we must-ism? Even if gas does still have any merit as a “bridge fuel,” shouldn’t polluting infrastructure go somewhere besides communities that have already long borne that burden?

But as far as southeast Pennsylvania is concerned, it probably doesn’t matter, Mikulska says: an export terminal is unlikely to be built.

“If you ask [industry sources or experts], is there going to be an LNG terminal in the East, they’ll say ‘Pssh, no way,’” Mikulska said.

Mikulska says that’s for a variety of reasons. In the U.S., permitting new fossil fuel infrastructure is a difficult process, especially in the more progressive Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions. That’s certainly the case in Chester, where Mayfield, the longtime environmental justice activist, has already geared up for battle, raising hell outside the closed doors of the first LNG task force meeting in April.

If EQT’s Rice liked Kazeem’s passion, Mayfield told Grid in a spirited, expletive-laden interview, “he just gonna love me.”

If I let you know you’re not welcome, you’re a fool to try and come anyway, but that message needs to be sent out.”

— Zulene Mayfield, Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living

Mayfield, founder of Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, says opposition is already organized and her group has plans to also begin attending the meetings of Delaware County–based political entities to pressure local politicians to take a stand.

“If I let you know you’re not welcome, you’re a fool to try and come anyway,” Mayfield said. “But that message needs to be sent out.”

In Chester, the political winds are also still shifting, after first-term City Councilmember Stefan Roots defeated mayoral incumbent Kirkland in this year’s primary, likely clearing his insurgent path to the mayor’s office.

According to his online biography, Roots previously worked for Philadelphia Gas Works and as an industrial operations employee for various companies, including Sunoco. And while Roots told Grid he has not yet studied the issue enough to know where he stands on the LNG proposal, he said he is generally of the philosophy that Chester’s waterfront should be moving away from its industrial past and toward mixed commercial and residential use, which gas opponents say offer longer-term economic and health benefits.

In the greater Philadelphia region, things don’t appear much better. Although the LNG task force on paper is studying any potential site for an LNG facility, all signs are currently pointing to Chester-or-bust.

Democratic State Rep. Joe Hohenstein, whose district incorporates Philadelphia’s River Wards, said he asked to join the task force out of a concern Port Richmond could be targeted for LNG export. But he quickly learned that, for various reasons, the port and others in Philadelphia are likely not a good fit. Hohenstein says he has stayed on the task force out of a general interest in the topic, with his staff hoping to ensure diverse perspectives are included in the final report, due this fall.

And international factors also play a role in limiting the likelihood of a local LNG facility, Mikulska said. New LNG supplies are already coming online, and long-term demand is uncertain. European energy customers are reluctant to sign long-term natural gas contracts. Developing nations are viewed as volatile and a credit risk. This all makes for a difficult pitch when a developer like Penn America tries to raise capital, with the company reportedly seeking between $4 billion and $8 billion in financial backing to build the Chester export facility.

“At least from my experience, it’s going to be very difficult for all those reasons,” Mikulska said.

It’s nothing new, but if you just push long enough and hard enough, get the right politicians in place and in play, and suddenly something starts moving. And that’s the worry here.”

— Maya van Rossum, Delaware Riverkeeper

So why bother creating a task force, when it has no formal powers beyond submitting a final report? White’s office did not make the representative available for an interview or respond to written questions. Sources in Harrisburg told Grid they could only guess at the genesis of her legislation and said generally there does not appear to be any major push by industry to prioritize the siting of an LNG export facility in the Southeast over any other infrastructure.

Still, others remain vigilant. The nonprofit Delaware Riverkeeper Network is heavily involved with other environmental groups in opposing a separate proposal to transport LNG by rail from Northeastern Pennsylvania to Gibbstown, New Jersey, just across the Delaware from the Philadelphia International Airport. From there, the LNG would be shipped overseas.

Maya van Rossum, the Dealware Riverkeeper, says opposition from her organization and other groups has been instrumental in creating a series of setbacks for the Gibbstown proposal. And in the task force and Chester proposals, she sees spokes of the same wheel, necessitating the same level of attention.

“We’re very concerned about the task force,” van Rossum said. “It’s nothing new, but if you just push long enough and hard enough, get the right politicians in place and in play, and suddenly something starts moving. And that’s the worry here.”

I see little attention to the concerns many have of the safety of transporting it once out of the pipeline. Please do a bit more research about spills and fires……about deaths and health. And look at the increasing pressure to invest less in fossil. This is not over.

Stellar journalism. I live and work a few short miles from Chester and have a vested interest in life quality here in Delco.