Philadelphia’s government is replete with plans to make the city more environmentally friendly. From climate change resilience, to reducing traffic fatalities, to urban agriculture, the City, its consultants and community stakeholders have spent enormous amounts of time and brainpower contributing to and drafting plans to make this a more sustainable city. It is intoxicating to imagine what the city would look like if all these plans were implemented.

But drafting a plan is just a starting point, and generally a lot easier than effecting change on the ground. Even well-intentioned leaders could run into unforeseen hurdles when it comes time to turn the plan into action.

Plans don’t carry the force of law, and they don’t necessarily translate into the political will to reach their goals. A cynical observer might interpret planning as something City leaders do to placate pesky advocates rather than actually expending the political and financial capital it takes to implement real change.

The new mayoral administration will need to decide what to do with the tall stack of plans it will inherit: which it will ignore, which will receive only lip service and which it will commit to.

Grid counted at least 20 such plans, as well as a couple of important initiatives worth mentioning. Although there are more plans than Grid can explore in one article, let’s take a look at some of the big ones.

Urban Agriculture Plan

What’s the Plan?

In November 2022 the City released a long-awaited urban agriculture plan draft. It was released on the website of Soil Generation, a Black and Brown led coalition of growers tasked with drafting the plan with consulting firm Interface Studio. The first public meeting for the plan had taken place in December 2019. The pandemic and other delays pushed the planning process back, and ultimately what came out toward the end of 2022 was a draft. More public input followed, including a December 3 Zoom meeting to present the draft plan.

The primary problems that the plan focuses on will come as no surprise to anyone involved with growing produce on vacant land in Philadelphia: food insecurity is concentrated in low-income Black and Brown neighborhoods, and growers there generally lack ownership of the land on which they raise crops. Gardens are particularly vulnerable in neighborhoods where gentrification and demand for more housing drives developers to build on the vacant lots that longtime locals have been caring for, sometimes for decades. Growers also need infrastructure (greenhouses, water, electricity, etc.) and struggle with low wages for agricultural work, among other challenges.

How’s It Going?

The draft plan calls for several ambitious actions. There are 25 alone under the land section, such as reducing the loss of growing space on private land sold in sheriff’s sales and creating a City land code specific to agriculture. None are final, though, since the plan is still a draft. A Parks & Recreation spokesperson told Grid that the final report is due in the spring of 2023.

Zero Waste and Litter Action Plan

What’s the Plan?

At the end of 2016 the Kenney administration issued a plan to cut the city’s waste stream down to zero by 2035. The goals went beyond simply picking trash up on time, getting litter off the streets and stopping illegal dumping. Getting to zero waste also meant increasing recycling and composting and coming up with creative solutions to cut back on everything we throw away. The strategy spelled out in the plan focused on waste reduction and diversion in buildings and events, engaging the public in reducing and diverting waste, and developing citywide programs to cut waste, say by establishing an organics collection program for composting.

At the heart of the plan was the creation of the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet, a multi-

departmental team chaired by a staff position (filled by Nic Esposito, until recently Grid’s director of operations) that could set targets for waste reduction and coordinate to solve problems that cut across the city government.

One thorny waste conundrum was how to tackle illegal dumping, a problem whose solutions necessarily involve multiple departments including the Streets Department (which functions as the City’s sanitation department), the police department, the district attorney’s office, and Parks & Recreation, whose parks are where a lot of trash gets dumped. The cabinet studied the problem and worked out how to fight it, for example by having the police department dedicate detectives to environmental crimes and ensuring that the DA’s office devoted attention to prosecuting the cases once the police had finished their investigations.

How’s It Going?

Up until 2019, it was going pretty well. Successes included developing plans for a city composting pilot, working with City Council to pass legislation to better regulate the tire waste stream (tires are often dumped illegally), and working with City building managers to identify barriers to recycling for City staff and for the public at their facilities. Then the pandemic hit, and the Kenney administration, citing budget constraints, cut the staff position coordinating the cabinet and the plan, thereby effectively dissolving the Zero Waste Cabinet. Reporting on progress toward the zero waste and litter goals ceased, making it hard to evaluate progress, and it appears that the cabinet’s initiatives have largely fallen by the wayside. Recycling in the city has declined to 2007 rates, and although the Streets Department has touted a recent civil prosecution of an illegal dumper, consequences for dumping remain rare.

Climate Action Playbook

What’s the Plan?

The Climate Action Playbook collects action items from other City plans that have something to do with climate change, making it a compendium of plans rather than a plan on its own.

Climate change is the biggest environmental challenge facing Philadelphia and its residents, and it’s hitting the city from all sides. As a warming climate drives more moisture and energy into the atmosphere, storms are growing more intense, bringing extra rain in heavy doses to a landscape with flooding and stormwater drainage problems. Sea level rise will increase flooding along Philly rivers: the Delaware is tidal along its entire course in Philadelphia, as is the Schuylkill up to the Fairmount Dam. Rising water levels will exacerbate storm surges pushed upriver by hurricanes.

No natural disaster kills more Philadelphians than heat. As the city warms, heat waves could claim more lives, particularly in neighborhoods with less tree canopy, disproportionately inhabited by Black and Brown Philadelphians.

As a compendium of plans, the playbook contains many wide-ranging action items that it divides into three categories: reducing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the use of nature to soak up carbon and adapting to the changing climate.

When it comes to resilience, the City places businesses and residents in the path of future disasters.

How’s It Going?

The City has some small successes to point to in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, though many of these consist of further planning, benchmark setting and strategizing. For example, one success is the release of a clean fleet plan that aims to shift the City’s fleet of 6,400 motor vehicles to electric, but it remains to be seen how quickly the City will actually shift to an electric fleet. In the meantime, the City lacks a plan to encourage private electric vehicle ownership. The city government has seen more success in reducing emissions from its built environment. The 2022 Municipal Energy Master Plan update reported that electricity and heat consumption and greenhouse gas emissions are dropping in government buildings.

In the meantime, other City initiatives march forward that increase greenhouse gas emissions with apparently little thought of climate impact. For example, the City-owned Philadelphia Gas Works continues to work to expand the use of fossil gas in the city, and the airport is expanding its cargo facilities, thus promoting the most carbon-intensive way to ship.

When it comes to using nature to soak up carbon, the City strives to increase the tree canopy, but it fails to protect existing canopy, even in its own parks (see the March 23 Tree Plan release article at gridphilly.com).

When it comes to resilience, the City places businesses and residents in the path of future disasters, most glaringly in the rapidly developing Navy Yard and on Venice Island. Meanwhile environmental justice neighborhoods like Eastwick have found themselves further exposed to future flooding as tree canopy upstream in the Darby-Cobbs watershed is cleared for City golf course renovation. In recreation sites, heat-absorbing grass fields are increasingly replaced by artificial turf that instead reflects heat right back out, turning playing fields from oases into ovens.

The City’s 2017 All Hazard Mitigation Plan, which aims to reduce the impact of disasters, included an objective to “integrate hazard and risk information into land use planning mechanisms” that was basically repeated in the 2022 update: “integrate hazard and risk information into land use planning decisions.” Nonetheless it is hard to find a development project that has been halted by climate resilience concerns, calling into question the will of City leaders to sincerely follow through on any plans in the playbook.(In a rare example, in 2012 Eastwick residents successfully fought off development plans in their flood-prone neighborhood.)

Vision Zero

What’s the Plan?

Vision Zero seeks to eliminate traffic deaths through a systems approach. Motorists, pedestrians and cyclists sometimes make mistakes, but a properly designed system will minimize and account for those errors and prevent accidents. The movement got started in Europe but has gained momentum in the United States. In Philadelphia, Vision Zero seeks to eliminate traffic deaths by 2030.

Philadelphia has a high rate of traffic deaths compared to peer cities (6.3 per 100,000 residents — twice as high as that of New York City). Vision Zero seeks to take that number down to zero by slowing cars, designing roads to be predictable for all users, promoting the use of safer vehicles and using quality data to identify dangerous roads. It particularly targets the 12% of Philly roadways responsible for 80% of traffic deaths (the “high injury network”) with improvements such as head start walk signals, protected bike lanes and speed cameras. It also emphasizes technologies such as red light cameras to enforce traffic laws rather than active policing, given the racist application of traffic laws and increased risk of police violence for drivers of color.

How’s It Going?

Vision Zero had a positive impact on traffic deaths (not including those on interstate highways), which dropped from 98 in 2016 to 83 in 2019. Then the pandemic happened, and, as anyone living in Philadelphia for the past three years knows, pandemonium ensued. Traffic deaths spiked to 156 in 2020. Including on the interstates, traffic deaths went from 91 in 2019 to 166 in 2020, according to a Bicycle Coalition report. They’ve been dropping since then, with 125 in 2022. Other troubling trends have emerged, however, with increasing numbers of drivers leaving the scene of fatal accidents.

Green City Clean Waters

What’s the Plan?

In 2011 the Philadelphia Water Department adopted a plan, Green City Clean Waters, to reduce the amount of sewage that flows into waterways. Most of the city’s water management needs are met by a system that combines stormwater and sewage. Heavy rains overwhelm the system, forcing combined stormwater and sewage to be released into creeks and rivers — about 14 billion gallons per year before Green City Clean Waters. Green City Clean Waters uses “green” infrastructure — trees and other vegetation — to soak up or slow rainwater, since reducing the volume of stormwater entering the drainage network should cut the combined sewage overflows. The green infrastructure supplements “gray” infrastructure fixes to pipes, treatment plants and other structures that the City is also making.

How’s It Going?

The Philadelphia Water Department celebrated the 10-year anniversary of Green City Clean Waters in 2021, and its 10-year progress report (submitted in May 2022 after an extension granted due to the COVID-19 pandemic) to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and the United States EPA shows that the city is on target in reducing the volume of the stormwater-sewage soup that pours into local waterways, so far cutting it by about 3 billion gallons. Grid asked the Water Department how much of that reduction can be attributed to the green infrastructure. According to a spokesperson, it is nearly impossible to separate the impact of the green infrastructure from the gray. To be clear, greening a city provides more benefits than just stormwater capture. More trees and rain gardens using native species help support local biodiversity and provide beauty and cooling shade to neighborhoods across the city.

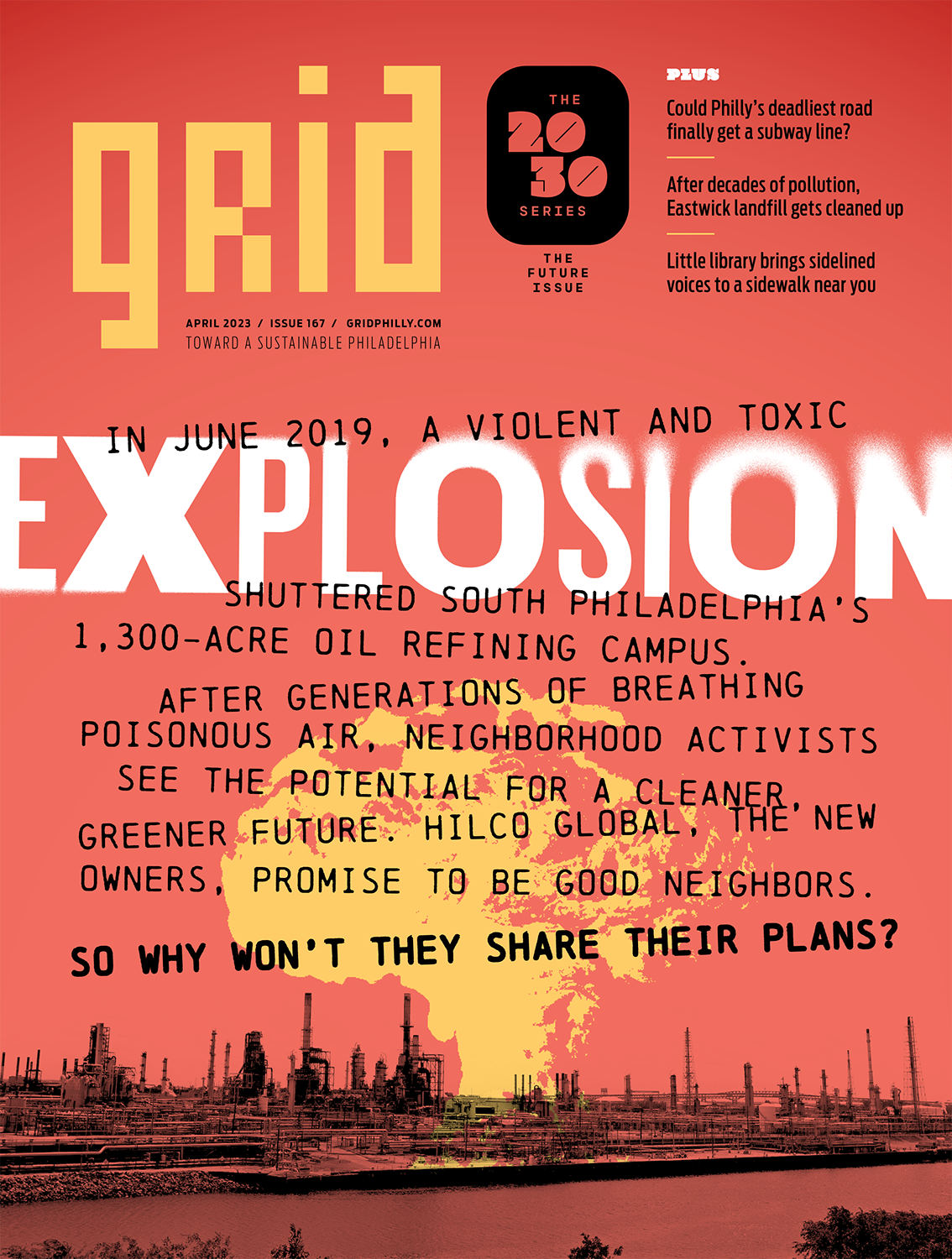

Environmental Justice Advisory Commission

What’s the Plan?

The Environmental Justice Advisory Commission is not really a plan, but as a critical environmental initiative it needs support from the next mayor. The importance should be obvious. The impact of environmental problems such as pollution, flooding and dangerous summer heat, to name a few, fall disproportionately on the shoulders of Black and Brown communities. Prominent examples include Gray’s Ferry residents who have lived next to the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery complex, inhaling everything it pumped out, and residents of Eastwick, who have had to deal with flooding, rampant illegal dumping and pollution from the Clearview landfill. The city government needs to understand and work to address the concerns of environmental justice communities. City legislation created the commission in 2019, and it was launched in February 2022.

How’s It Going?

Although it took a while to get off the ground, the commission is now taking action. As an advisory body it can elevate concerns and solutions, but it cannot force action. Its impact depends on what City leaders do next. Will the next mayor listen?

Rebuild

What’s the Plan?

Operations, including maintenance, is woefully underfunded at Philadelphia Parks & Recreation facilities, and it has been for decades. Little things fall apart and don’t get fixed; big things get patched in temporary ways. It all adds up to what people in government refer to as “deferred maintenance.” For people served by the government, it adds up to broken playground equipment, dank and smelly recreation center bathrooms and environmental centers closed through the winter because there’s no heat. Rebuild, an initiative launched in 2017 as a marquee program of the Kenney administration, promised a solution. A capital program (there is a technical but critical distinction in budgeting here — operations budgets mostly come out of taxes, while capital budgets are generally funded by government debt, i.e. selling bonds) would pay for renovations to run-down park and recreation facilities and libraries. The City would make payments on the bonds with proceeds from the sugary beverage tax. Problem solved! Back when it was launched, Rebuild was budgeted at $500 million, which included $300 million from the bonds plus another $200 million from foundation grants and other fundraising. That would pay for renovations for 150 to 200 facilities.

How’s It Going?

Right out of the gate Rebuild ran into its first hurdle, and it was a big one. Opponents of the sugary beverage tax sued to stop it, and the City banked the sugary beverage tax proceeds for two years until it won the lawsuit, since it didn’t want to be stuck with a whole lot of bonds it couldn’t afford to pay back. In 2018 the City started issuing bonds, and construction got moving, albeit slowly. Then the pandemic hit, and with it an economic roller coaster of supply chain disruptions (remember the spike in lumber prices in 2021?) and inflation. Now it looks like the City will be able to address 72 projects.

But even if Rebuild had met all its initial goals, it was never in its mandate to solve the fundamental underlying problem, which is that the City woefully underfunds the maintenance of its parks and recreation center infrastructure. Back in 2016, the William Penn Foundation (which funds Grid) provided $100 million to Rebuild and funded a strategic plan that sought to improvebParks & Recreation’s maintenance system. As Grid has reported in articles about inequity in parks maintenance, the department still suffers from a massive deficit of funding compared to its needs. Shiny new recreation centers, playgrounds and playing fields will all fall apart without proper maintenance, just like everything else in the parks and recreation system. To give Philadelphians the parks, pools, playgrounds and rec centers that they deserve, now and in the future, the next mayor and City Council will need to fully fund operations and maintenance.

PGW Business Diversification Study

What’s the Plan?

Geothermal could take advantage of PGW’s physical infrastructure and labor force, but the utility hasn’t exactly leapt to the challenge.

The Philadelphia Gas Works is in trouble. As Philadelphians adopt more-efficient appliances and make the switch to electric fuel for cooking and for heating their homes and water, demand for gas is falling. Moreover, emissions from burning methane (the primary fossil gas that PGW sells) are an important part of the greenhouse gas puzzle the City needs to solve, and the necessary reductions in emissions will result in a further erosion of PGW’s business. As revenue falls and fixed costs (such as maintaining the network of pipes that distribute gas) remain the same, the utility is forced to raise the price of methane, motivating consumers to cut back even more, leading to more rate hikes, what could be called a utility death spiral.

In an effort to force PGW to wake up to reality, the Office of Sustainability led the PGW Diversification Study in 2021, which tried to point a way to a sustainable (in environmental and business terms) future for the utility. It presented a set of options, with the most practical one being a shift in PGW’s business model to providing geothermal heating and cooling. Geothermal heating and cooling systems rely on the constant, moderate temperature underground to heat or cool air. Pipes underground carry fluids that pick up heat from the earth, which in winter remains warmer than the air. The warmed fluids are then run through a compressor that conveys the heat to the home or other space in need of warmth. In summer, when the earth is cooler than the hot air above, the system can essentially operate in reverse to provide air conditioning. Since these systems involve laying and maintaining networks of pipes, pumps and wells, PGW should be well equipped to operate them.

How’s It Going?

Geothermal could take advantage of PGW’s physical infrastructure and labor force, but the utility hasn’t exactly leapt to the challenge. PGW continues to pick up new customers, as happened in 2022 when Amtrak opted to switch 30th Street Station from Vicinity’ Energy’s steam loop to gas. Under lobbying pressure from environmental advocates, PGW included $500,000 in its current operating budget to study a shift to providing geothermal heating and cooling. Based on a progress report PGW submitted to its City oversight board, the Philadelphia Gas Commission, the utility has begun the feasibility study.