In July 2020, after spending several months of the pandemic wondering whether her trash and recycling would be picked up, Sarah Ausprich was frustrated. When it was collected, Ausprich, a resident of Philly’s East Passyunk neighborhood, watched sanitation crews repeatedly combine her trash and recycling in the same truck. Disillusioned by curbside collection, she decided she would hold onto her recycling and take it to one of the city’s six sanitation convenience centers every few weeks.

Her first trip went smoothly, and the center had two separate trucks on site for trash and recycling. On her second trip, though, she encountered only one truck — a trash truck. The worker staffing the center insisted that her recyclables were dirty and therefore trash, even though she had been storing them in her clean and dry basement. With no other option, she begrudgingly tossed her recyclables into the truck and left feeling dejected — and determined to make sure it didn’t happen again.

I don’t recycle through the City at all anymore.”

— Sarah Ausprich, Philadelphia resident and dedicated recycler

Thus began Ausprich’s journey to cobble together recycling alternatives that didn’t rely on the Streets Department or the blue bin. She takes her glass to Bottle Underground in the Bok Building. Aluminum cans go to a scrapyard in Northeast Philly. Rabbit Recycling takes her plastics, paper goes to a middle school near her sister’s house in Delaware County and she finds people to donate her cardboard boxes to through neighborhood Buy Nothing Facebook groups.

“I don’t recycle through the City at all anymore,” says Ausprich. “I don’t trust that it won’t end up contaminated or mixed in with trash. It’s really disheartening.”

Ausprich isn’t alone in her sentiments. Other residents, like Fishtown’s Kate Zmich, have opted out of recycling through the City.

Zmich takes glass to Bottle Underground, and she uses Rabbit Recycling for many other recyclables. In addition to losing faith that the City would manage recycling properly, she was motivated by a desire to lighten the load for sanitation workers, whom she began to feel were not being adequately supported by the Streets Department during the pandemic.

“It came from knowing recycling in Philly is a mess, and it came from the mismanagement of the workers, and knowing that leadership doesn’t prioritize it, and not wanting to burden the workers with these materials,” says Zmich.

After making substantial gains in recycling during the Nutter administration, Philadelphia has backslid over the course of the Kenney administration to the point where recycling statistics are now almost to the level they were in 2007 under Mayor John Street — before the Nutter administration rolled out single-stream recycling and boosted the city’s recycling rate from 7% to a high of 21% in 2015. Once again, Philadelphia’s recycling rate is 8%: almost a decade’s worth of progress — erased.

“The Streets Department is reverting back to a waste collection agency, and it’s putting everything in the trash,” says Maurice Sampson, Eastern Pennsylvania director for Clean Water Action and the City’s first recycling coordinator from 1985 to 1987. “We have a department whose mentality is disposal and not recovery.”

Grid asked what the plan is to increase the recycling rate to recapture the losses of the last several years, but a Streets Department spokesperson had not yet responded at press time.

How did Philadelphia get here after almost a decade of steady progress on recycling and better waste management?

At the beginning of the Kenney administration, it looked like the City was poised to build upon the gains of the Nutter administration and propel Philadelphia to an ambitious goal of zero waste by 2035. Kenney established the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet (ZWLC), led by director Nic Esposito out of the Managing Director’s Office. (Esposito is director of operations at Grid, and cofounded Circular Philadelphia with the author.) His office was to take a holistic approach to addressing thorny waste issues that require cross-government collaboration, like litter and illegal dumping.

Prior to the establishment of the ZWLC, recycling and waste concerns were largely within the purview of the Streets Department. (The City’s Recycling Office was subsumed into the department in 1998.) Since then, there have been extended periods of time when the recycling for Philadelphia, a city of 1.5 million people, has had a dedicated staff of one or two people.

Despite this, the Nutter administration made hefty gains in the city’s recycling rate, attributable to the rollout of single-stream recycling and the Recycling Rewards program, which incentivized residents to recycle. The Streets Department regularly shared recycling rates, and outreach and education was targeted to neighborhoods where rates were lower.

Under former Streets Commissioner David Perri, the Nutter administration began to approach waste management holistically to improve efficiency and promote alternatives to disposal. The department started looking at the possibility of franchising commercial waste collection, like in New York City, to reduce the number of trucks crisscrossing the city daily to collect waste from businesses. It also began investigating how to eliminate dumpsters from city sidewalks and alleys, an act that would most likely boost waste reduction and recycling as businesses sought alternatives to throwing things away while making our streets cleaner and the air less foul.

After the ZWLC was created, the City supercharged its use of data to create the citywide litter index and focus scarce resources for anti-litter, cleaning and illegal dumping where they were needed most, like Kensington and Southwest Philadelphia. Perhaps even more importantly, the ZWLC set waste and litter reduction goals for the city and published regular reports to the public that showed the progress the city was making, backed up by data.

“To use data as an integral part of the actual operation with a mandate to engage the community in the process to listen and learn and act and build a citizen-institutional

coalition could really go beyond what had been done with waste management in the city,” says Mike DiBerardinis, former managing director for Mayor Kenney. “To move from a reactive position to a proactive position was an important shift.”

Daniel Lawson, sustainability and quality control manager for Philadelphia Parks & Recreation at the time, also saw the value of using a data-driven approach to manage waste within the City’s own operations.

“I saw the power of the data,” says Lawson. “Having someone on the ground to visit rec centers and do inventories on recycling and to generate diversion rates and contamination rates was my primary tool to bring together leaders in the department and show them why we need to continue to do this.”

But this push to create goals, use data and report progress didn’t appeal to everyone in government. Even though the Streets Department was the “anchor organization” for the ZWLC because of their role in carrying out the work needed to meet goals set by the cabinet, they weren’t completely on board.

“The idea was to give Streets a roadmap that they helped create that they would use for the journey,” says DiBerardinis. “They were very resistant.”

Still, it appeared as though the City was making real progress towards its zero waste goal, and then the Streets Department, under the leadership of current Streets Commissioner Carlton Williams, allowed the City’s recycling contract to expire, resulting in the incineration of half of the city’s recyclables for a period of six months beginning in October 2018.

When the pandemic hit, Mayor Kenney abolished the ZWLC due to “budgetary concerns,” and sanitation operations fell apart, partly due to high rates of sanitation worker absence due to COVID-19 and fear of getting sick. “During the pandemic, morale was [historically low]. Nobody wanted to come to work,” recalls Terrill Haigler, a former sanitation worker who rose to fame as “Ya Fav Trashman” during the pandemic due to his frank, daily dispatches on Instagram that let Philadelphians know what was happening with trash and recycling collection. “There was no clear-cut communication from Streets on what was going on.”

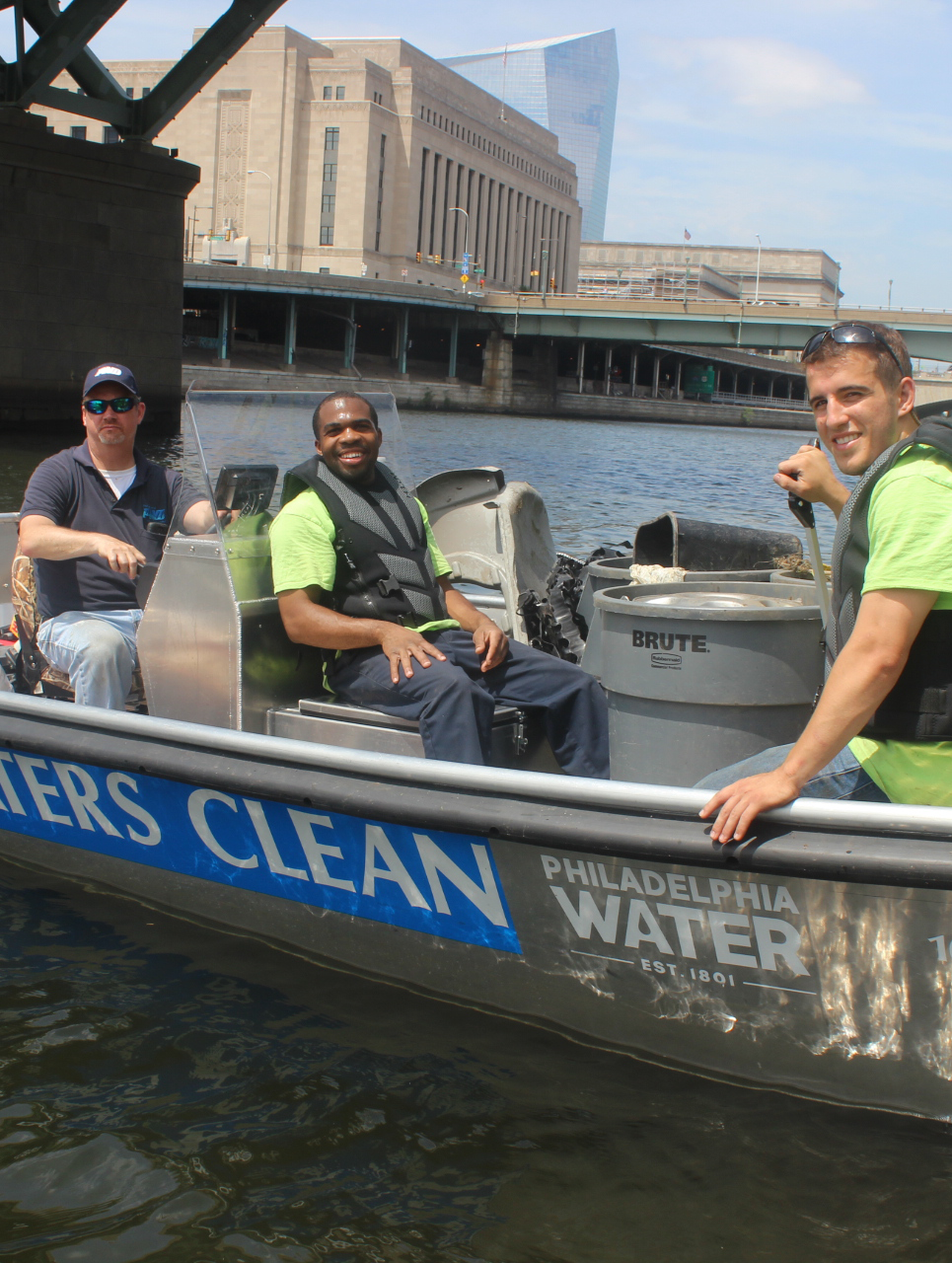

The Streets Department was unprepared for a high worker absence rate and the increase in residential trash and recycling due to Philadelphians being stuck at home. This resulted in trash and recycling going uncollected in some neighborhoods for weeks at a time during the summer of 2020. The Streets Department repeatedly assured residents at the time that pickups were back to normal, and that trash and recycling were no longer being combined, but residents reported seeing trash and recycling being emptied into the same truck for two years after the pandemic began, according to reporting by Billy Penn. As a result, the Streets Department destroyed what little trust residents had left in their ability to manage materials properly after the recycling incineration fiasco of 2018.

“The last excuse I heard was that they are dumping recyclables and trash into the same trucks and then sorting the recyclables at a proper facility,” says Kathryn Nalley, a Kensington resident. “Am I actually supposed to believe that? I already assumed that most of the stuff in my recycling bin wasn’t being recycled, so I certainly don’t think anything recyclable is actually being recycled after being mixed with garbage.”

“You can’t BS the public,” says Perri. “Eventually they’ll find out.”

With no ZWLC left to drive the City’s zero waste goals, communicate with residents and broker the intra-departmental collaboration needed to tackle the city’s litter and dumping issues, many of the responsibilities fell to a Streets Department with little interest in carrying on the work, no pressure from the mayor to do so and no credibility in the eyes of Philadelphians.

One of the best things that [Mayor] Kenney did was set up the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet, and the worst thing he did was dismantle it.”

— David Perri, former Streets Department commissioner

“Without the executive authority and the resources, you’re done,” explains DiBerardinis. “You can continue doing the day-to-day, but if you’re going to impact the big environmental issues of today and tomorrow in the city, you need the blessing of the executive and the commitment down the line from the commissioners to carry out this work.”

“One of the best things that Kenney did was set up the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet, and the worst thing he did was dismantle it,” says Perri.

“Where we are is predictable,” says Sampson. “As long as the mayor wanted this, it happened. Once he didn’t, it didn’t happen.”

It’s not entirely clear why Mayor Kenney seems to have lost interest in ensuring Philadelphia makes it to that 2035 zero waste goal that his own administration set. But the current state of the waste industry may offer a clue.

Currently, almost all recycling in the United States is handled by the four largest waste companies, including Waste Management, who holds Philadelphia’s recycling contract. These companies all own and operate landfills, and the margins on tipping fees at landfills in the Northeast are much higher than the margins on recycling. To make it worth it for these companies to offer recycling services to cities, they must charge high prices for recycling to compete with the fees they receive for landfilling.

When recycling fees are as high as landfill tipping fees, it creates a disincentive for municipalities to bother with the extra work of separating their waste for recycling. One Philly-area waste management professional with decades of experience in the industry that Grid spoke with for this article predicts that without state regulations that require counties to recycle, a lot of them would stop recycling altogether.

Waste Management’s landfill ownership also means that there’s little reason for them to care about whether recyclables that enter their facility ultimately end up recycled because they don’t have to pay extra to dispose of any materials that fail to find a market for recycling. In Philly, this means that anything that doesn’t get recycled ends up landfilled or incinerated, contributing to climate change and causing health and quality-of-life issues for the low-income communities of color located near these facilities in places like Chester, Delaware County — one of the places where Philadelphia’s trash goes.

The City could mitigate some of these disincentives through better waste and recycling contracting. Philly’s recycling contract expires at the end of June 2025. If the Streets Department was serious about finding alternatives to Waste Management to handle recycling — and possibly add composting — it would start the RFP process in the next six months, according to a Philly-area waste management professional who is familiar with how Philly’s recycling contracts work.

However, if it waits until six months before the contract expires as it has in the past, Waste Management will likely be the only bidder. This means they can set whatever conditions and price they want, and it will most likely cost the City more.

So where does Philadelphia go from here? To have any chance of moving towards a low-waste, circular economy that is so critical to the future of our city and planet, Philly must first get the basics right.

“I believe it’s not recycling that’s broken. Waste management is broken,” says Sampson. “We have mechanisms to make the waste management system work, but we don’t put them together.” Sampson suggests that the next mayor needs to recognize that the system is broken and needs to be fixed, and then he or she needs to install the right leadership to do it.

“We need to hire professionals and allow them to run the Streets Department,” insists Sampson.

With the way the Streets Department is currently structured — being responsible for both streets engineering and sanitation — an outsized amount of the city’s quality-of-life issues, like picking up trash and recycling, cleaning litter and dumping, and filling potholes, fall on the department to manage. It’s too much for one department to handle, and the City’s most recent former sustainability director, Christine Knapp, believes that breaking the department into two parts that can focus separately on roadways, traffic and public right of ways and sanitation and solid waste makes more sense. It would allow each department to do a better job addressing these issues.

“If you have two separate departments, you’re more likely to have commissioners and staff with more specialized expertise,” says Knapp. Professionals, like Sampson advocates for, rarely have expertise in both streets and sanitation. While some Streets Department commissioners prior to Williams have been engineers, there’s still been a steep learning curve to make the entirety of the department function well.

Creating a separate sanitation department may also solve an issue that others have indicated: planning—which doesn’t really exist now within the Streets Department but could be incorporated into a new department—needs to have influence over operations.

“You can’t have a planning department without two things: they need to have money (or budgetary authority) and they need to have formal reporting authority from Streets,” says DiBerardinis.

Former Streets Commissioner Perri suggests that there also needs to be someone at the deputy mayor level in charge of cross-departmental waste-related issues, similar to the position of the former ZWLC director. Lawson also supports this solution.

“A very simple thing to do would be to reinstate the functions of the ZWLC. Those functions that existed have not been effectively picked up by another entity,” says Lawson. “That cabinet was getting some real work done and making some real progress. Reinstating that will elevate this waste diversion work as a priority.”

Then there are a host of improvements the City could make when it comes to how it collects waste and recycling. Both Perri and Sampson agree that to help curb illegal dumping, the City should bring back collection of bulk items, like refrigerators and couches, that are frequently found in dumped piles of trash.

Haigler believes the City should explore automated collection in some neighborhoods, as it would reduce the toll that collecting trash takes on sanitation workers’ bodies. This could be combined with improving how the Streets Department routes trucks by employing GPS to make collection more efficient and able to adapt to changing route conditions.

“What I saw from the beginning was a lack of a systematic flow,” explains Haigler. “Sometimes in the middle of the day, they’d switch the route. Or you’d almost be done and they’d be like, ‘You need to get nine more blocks.’”

Repairing the trust has to come from transparency.”

— Terrill Haigler, former sanitation worker and City Council candidate

And how to get Philadelphians’ trust back? Residents say that can only come from transparency and open communication.

Sabrina Murphy, another Fishtown resident, says the City could regain her trust with “a communication campaign to explain and address the rightful uncertainty with how they have been handling recyclable waste, what their plan is now and if they cannot commit to actually recycling our recyclables, what are the suggested alternatives to ensure citizens can still do the right thing.” She adds, “I believe most people want to do the right thing but they want/need direction and transparency.”

Haigler, who is running for City Council, agrees. “Repairing the trust has to come from transparency,” he says. “And then the openness to hear suggestions and to shift and do things different from how you’ve always done them.”

Making these changes may seem like a tall order, but they are necessary if the next mayor wants to make serious progress on mitigating Philadelphia’s contributions to climate change, improving quality of life for all Philadelphians and winning back the trust of residents.

“When you think small, you necessarily act small,” says DiBerardinis. “ When you think big, you don’t necessarily win, but your chances go way up.”

This is an excellent, and much needed, article. I see that Terrill Haigler is running for City Council…he has my vote! I believe that most Philadelphians will do the small bit of extra work to properly separate their trash from recyclables. I am so sick of the nickname Philthydelphia but it is justified…so many neighborhoods have trash dumping imposed on them and I regularly observe trash being thrown out of car windows, all over the city. Disgusting habit!

Thank you so much for sharing. I have to say that here in Miami, it’s the same issue, even openly expressed. The County doesn’t care about trash segregation. They collect everything in the same truck. In Doral, the odor is terrible on 74th Ave. I have big concerns about people’s health and future consequences. Creating an environment-friendly culture in companies is really hard when you have this type of issue with Waste Management. We need to start educating people so we can push and pressure the system. I would like to contact Sarah Ausprich and share ideas to implement them here in the Sunshine State!