In one of the world’s most polluted urban watersheds, in the shadow of shuttered refineries, stands FDR Park, a miraculous sliver of natural topography. The City intends to use it as something of a retaining wall supporting vast elevated terraces topped with artificial turf fields.

When development projects are proposed on City-owned land, the City is supposed to conduct a cultural resource assay. Plans to develop FDR Park, then, prompt the question: Is anything there worth saving for cultural reasons? The answer, it turns out, is a resounding yes: On the South Philly golf course that has become the beloved South Philly Meadows, just west of the fairway and green of the 15th hole, the world-famous Seckel pear was born.

“…the finest pear of this or any other country” is born

The turf fields will obliterate what was known in the 18th century as Mason’s Hill, a slight rise overlooking where Shedbrook Creek once met Hollander Creek. It was land that—dry amidst the marsh—would have likely attracted Lenape and Swedish habitation. Using your mind’s eye to disappear the interstate and the Navy Yard, you can imagine this hill affording fine views of Hollander Creek flowing to the back channel.

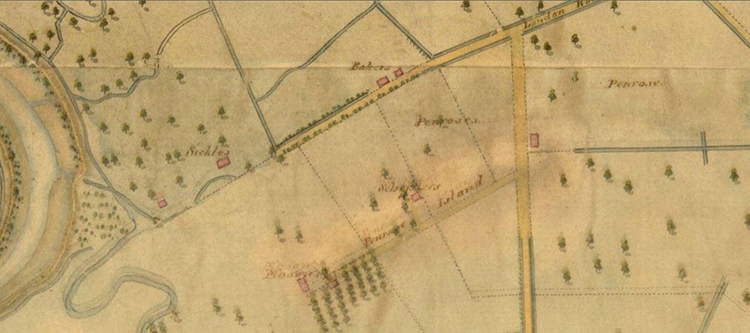

By the 1760s, two German families lived on the banks of Hollander Creek, taking advantage of the excellent farming on the small marginal uplands bathed by the tides. On the southwest flank of Mason’s Hill lived Lorenz Seckel. On the eastern side of Hollander lived Jacob Weiss. In the mid-18th century, Weiss was growing—and guarding—a stash of new pear trees, which he carefully distributed to friends and family. It is surmised that Weiss shared these pears with his countryman, but Seckel was less discriminating in his distribution, and the delicious new variety was soon being marketed under his name.

[The Seckel is] the finest pear of this or any other country.”

— William Coxe, 19th century New Jersey pomologist

The fruit had garnered such acclaim by 1817 that the noted New Jersey pomologist William Coxe was already asserting in “A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees” that the Seckel pear “is in the general estimation of amateurs of fine fruit, both natives and foreigners, the finest pear of this or any other country.”

In 1819 Alexander Hamilton’s attending physician and botanist David Hosack sent specimens of the Seckel to the Horticultural Society of London, noting its Philadelphia origin. English pomologists declared it “one of the best fall-ripening pears,” and the fruit fast became an emblem of national pride.

The fruit’s image was further burnished by a high-profile endorsement: the noted landscape architectural tastemaker Andrew Jackson Downing praised the pear’s fine flavor and touted its suitability for domestic gardens. In an extended footnote in “The Fruits and Fruit Trees of America” Downing relates that on “a fine strip of land near the Delaware” Jacob Weiss first grew a pear of “high flavour … as yet unsurpassed, in this respect by any European sort,” proving “the natural congeniality of the climate of the northern states to this fruit.” Downing further notes that Stephen Girard, an industrious agronomist who managed a plethora of properties in Passyunk Township, likely recognized the parcel’s historic value, and purchased it. “The original tree still exists (or did a few years ago), vigorous and fruitful,” reports Downing, further noting to its longevity that “specimens of its pears, were quite lately, exhibited at the annual shows of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society.”

Girard snapped up Lawrence Seckel’s 108 acres and 70 parcels, comprising an area known as “Schuylkill Point meadows,” at a sheriff’s sale in 1832. As

Downing mentions, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society found Girard’s orchard management superb with “universal health among the trees” noted during a tour. Girard’s property, “situated on the Neck between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers” also contained “the original Seckel pear tree, from which has been propagated the most luscious pear in existence.”

The old Seckel farmstead, occupied by a tenant of the Girard estate, became the site of many a pomological pilgrimage in the 19th century. In 1849, the year the American Congress of Fruit Growers unanimously affirmed that the Seckel was “worthy of general cultivation,” the horticulturalist Dr. W. D. Brinckle reported in “The Cultivator” that “the original tree still stands on the banks of the Delaware, three and a half miles below Philadelphia.” Dr. Brinckle described the tree as about 30 feet tall, about two feet in circumference, and “hollow and decayed on one side.”

Dispatches on the tree’s health continued to flow to horticultural journals. The correspondent Jafet, admitting that information regarding the tree’s existence from an old “Necker” “began to haunt” him, wrote of his visit to the ancient tree in the September 1880 edition of the “Gardener’s Monthly.” Coming upon the telltale markers he was told to expect — “the old stone house, the sloping meadow and the ditch” — he encountered a Mr. Bastian, tenant farmer current custodian of the declining pear tree. “The fraction of all that remains of the old stormbeaten, ancestral Seckel Pear is 26 feet in height,” Jafet reported. Publisher of Gardener’s Monthly Charles H. Marot also sold photographs of the tree, urging readers in advertisements to “secure something more than a mere tradition.”

The archaeologist’s quest to document the famous tree

When Dr. Henry Mercer, the noted archaeologist, artist and preservationist, set off in search of the Seckel in 1909, he was embarking on another sortie in his lifelong rearguard action against the leveling effect of industrial modernity. Like Jafet, Dr. Mercer was moved to explore Philadelphia’s low country, and with historian Anthony Hance he visited the Seckel pear’s stump several times in 1909. Bounding amidst sodden “land being reclaimed from river silt by man’s genius and mastery of engineering,” they still found ancient references to guide them. Hance told Mercer about the venerable Cannonball House then standing on the other side of the Schuylkill, so named because it bore the ballistic remains of the British violence wrought during the siege of Fort Mifflin in 1777. It was demolished by the City in the 1990s.

A year before Hance and Mercer’s adventure, pomologist H. P. Gould of the U.S. Department of Agriculture had visited the site. Learning that the tree had been dealt a final, deadly blow by a storm in 1905, Gould photographed the old Seckel homestead and the location of the stump in 1908. He erected a whitewashed marker at the site of the submerged stump; this allowed Mercer and Hance to remove a relic of the tree to the Bucks County Historical Society.

Mercer and Hance returned in April 1909 — with the permission of the Girard Estate — to take 12 grafts from the nearest living relative of the old progenitor, some of which made their way back to Mercer’s Fonthill estate. With the anthropogenic mud rising, Mercer was observing above-ground cultural artifacts slowly become archaeology in real time. So they wisely triangulated “the old tree between 24th and 25th streets on 42nd avenue in the 36th Ward” on a 1909 map.

With our access to digital cartographic resources, 21st-century Seckel seekers can now determine that the likely location of the Seckel homestead was the green of the old 15th hole, with the first Seckel pear growing near the fairway of the 14th hole.

Most of these spaces will be excavated and filled to the height of Mason’s Hill, forming a broad plateau of artificial turf fields terminating abruptly at an inaccessible 45-acre wetland.

Contrary to the belief of park master planners, the small knob of neck land called Mason’s Hill remained unchanged for most of the 20th century. Philadelphia-based Curtis Publishing Company’s “Farm Journal” urged visitors to the sesquicentennial to “walk or drive” to the corner of League Island Park to tread the ground that bore the first Seckel pear. Portions of Mason’s farm were incorporated into the League Island Golf Course itself, preserving this space for nearly three centuries. But the way the official League Island Historic District is delineated, nothing west of 20th Street has ever been surveyed for historic or archaeological resources. This despite the fact that the U.S. Navy recognized the Seckel pear’s origins nearby in their 1988 Environmental Impact Statement for a proposed trash-to-steam plant at Girard Point.

Like islands in the marsh, the story of Philadelphia’s own indisputably homegrown fruit gets concealed but always reemerges. The FDR Park plan’s failure to identify and draw strength from this foundational story of urban agriculture is a loss. One no less grievous than the destruction of an 18th-century pastoral landscape tucked away for 300 years. The Seckel pear is South Philly born and raised, no matter whether the landscape of its birth is marred by mitigation wetlands and artificial turf.

Nearly every seeker of the Seckel has opined as to why this plot of earth gave rise to the fruit, and it all comes down to the delicate interplay of land and water — of seeds caught in tidal surges and deposited on the sides of our fertile hillock. Encoded in that seed’s journey, too, is the true way forward for the design of this park: islands of permaculture in the meadows.

For ten years, Christopher R. Dougherty worked for the Fairmount Park Commission as a Historic Preservation Specialist, with Philadelphia Parks & Recreation as a Park Manager and the Fairmount Park Conservancy as project manager working in cultural resource and capital project management throughout the 12,000 acres of Philadelphia’s parks. Before leaving the Fairmount Park Conservancy in 2017 he managed the project scoping and design consultant selection for the FDR Park Master Plan. He has an MS in City & Regional Planning from Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture.

Hello there! I was just reading your article about the meadows at FDR and was wondering if you had any more info or know any organizations to team up with and help preserve them.

Thanks for your time!

Take care.

Jacob-

Please join People’s Plan for FDR! We’re working to stop this horrible plan as the destruction looms.

Here’s the website: https://www.pp4fdr.org/

Hit the ‘join the coalition’ button to get involved!