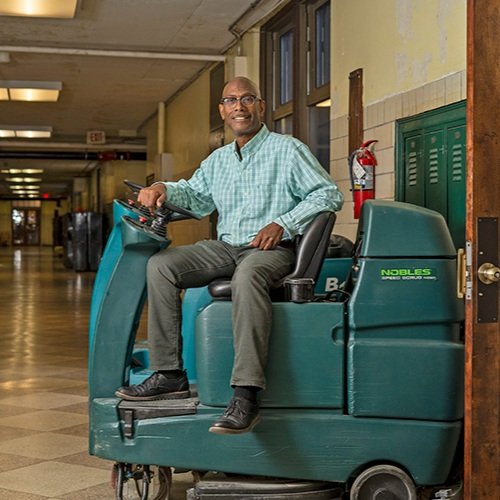

In a former municipal building on Rising Sun Avenue in Northeast Philadelphia, cycling enthusiast Rudi Saldia is doing something he never imagined: working at a desk.

It was a long and winding road—well, often a straight road on a grid—that led him to Bennett Compost’s Lawncrest headquarters.

Before the days of DoorDash and Grubhub, he was doing deliveries for restaurants. He was a messenger and courier with Sparrow Cycling. He even rode a pedicab for a while.

“Working on my bicycle has always been a passion of mine,” says Saldia.

When he was recruited by Bennett Compost to pick up organic waste by bicycle, the position almost seemed too good to be true.

“This was the first job [I’d seen] that offered cyclists full-time benefits and salary, which is pretty much unheard of,” says Saldia.

He was hired by Jen Mastalerz, a cyclist herself, who had just recently become a partner at the company. She has a long history in organic waste, first working for the Mount Airy-based Philly Compost and then starting her own business, City Sprouts, in Fishtown where she lived, picking up organic waste by bicycle at neighborhood restaurants, including Johnny Brenda’s and La Colombe.

“This was the first job [I’d seen] that offered cyclists full-time benefits and salary, which is pretty much unheard of.”

— Rudi Saldia, manager at Bennett Compost

On a small scale, she was able to make bicycle pickups work. “I found it very enjoyable and easy, weather permitting. And I had backup—a Honda Fit,” Mastalerz recalls.

But when she bought into Bennett Compost in 2018, she had a vision to push this model further.

“I really saw an opportunity with Philly being flat,” says Mastalerz.

Her business partner, founder Tim Bennett, however, was skeptical.

“I thought there was no way this could possibly work,” he remembers.

Mastalerz set out to prove him wrong. Through a grant from The Merchants Fund, Mastalerz had acquired a trike with a sizable bin in the front designed to transport a person in a wheelchair. When she rode it for her first Bennett Compost route, her optimism was tested. It took 13 hours to complete a route of 100 customers.

“Not efficient,” she says with a laugh. “It was a terrible day.”

Despite the inauspicious start, Mastalerz was undeterred. She was still pondering how to make bicycle pickups work when JT Look, the owner of the now-closed bike repair shop Fishtown Bikes-N-Beans, suggested Saldia as a hire.

Saldia proved to be exactly what Bennett Compost needed to launch the bicycle pickup service. His idea of fun was doing bike deliveries all week and then going for 100-mile rides on the weekend.

With his help, what once seemed like impossible bike routes became routine.

“Jen and I would regularly have conversations about whether this would be feasible without Rudi,” Bennett says.

The problem that they were facing was that, superhuman cycling aside, they didn’t have the density necessary to support pickup by bicycle.

“That route Jen did was a sprawling route that went from probably almost Port Richmond all the way down to the end of Northern Liberties … We now have five routes over two days [in that area],” Bennett says.

E-bikes are also part of the operation now. Tern GSD e-bikes (purchased from Firth & Wilson Transport Cycles in Fishtown) are outfitted with trailers, making hauling much easier.

But the key to their success has really been building customer density. Twelve years into business, Bennett Compost now has over 5,500 customers, and picks up organic waste from over 2,200 of those customers by bicycle. This has resulted in employment for three full-time cyclists.

“We’ve taken pride in our ability as we’ve grown to offer better employment opportunities.”

—Tim Bennett, founder of Bennett Compost

Saldia, who has been promoted to a management position, is not one of them. He will still fill in for a shift when necessary, but he no longer does pickups on a daily basis.

“On one hand, I miss riding my bike for work,” Saldia says. “But on the other hand, I now get to help grow the bike division of Bennett. I went from being the only full-time cyclist at Bennett to now managing a crew of three full-time cyclists. So even though I don’t ride my bike for work everyday, I still get to work with the bikers and keep this part of Bennett Compost rolling forward.”

A Business is Born

Twelve years ago, Tim Bennett was living in a second floor apartment in South Philly when he began looking at ways to reduce his impact on the environment and learned about composting.

Composting is a natural process. It’s the decaying of organic matter, and when it’s complete, the result is rich soil ideal for growing food. But managing that process can be tricky, especially if you don’t have access to outdoor space.

“[Composting] seem[ed] like something I should be doing, but I didn’t have a way to do it easily in my apartment in South Philly,“ he recalls. So he looked around for a place that could take his compost but didn’t find any good options. It occurred to him that others might feel the same way.

At the time, Bennett was working at Temple University’s Small Business Development Center, doing “very boring office management type work.”

“The nice thing about it was it exposed me to all these people who would come through the office who were trying to find ways to start various businesses. It was a great way to learn,” Bennett says.

He put $100 in a bank account to make the business official and hung flyers at coffee shops.

“A couple days later someone called me,” he says. “I was shocked.”

Throughout the summer of 2009, Bennett continued to hang flyers until he’d converted about 10 customers. By that point, he’d had built a relationship with a community garden where the organic waste could go.

Bennett did not own a vehicle, but he noticed there were low rental rates for pickup trucks, especially in the middle of the night, through the now defunct PhillyCarShare.

In early September 2009, Bennett took most of the money he had made, and signed up for Greenfest Philly, the annual festival of all things sustainable held in Society Hill. A novice to the scene, Bennett hung a sign around his neck that said “composting.” After the event, he looked in astonishment at the email signup sheet, and the 125 emails in his inbox the next day.

The demand for composting in Philadelphia was budding.

At that same Greenfest, Bennett met Alex Mulcahy, Grid’s publisher. The two forged a friendship, and before long they became partners in the business.

Eleven months after Greenfest, Bennett decided the time was right to make the leap and go full time.

“Alex’s belief in me, and the growth of people subscribing to the residential pickup, gave me the confidence to go all in.”

In 2020, fueled by a surge during the pandemic, Bennett Compost signed up their 5,000th customer.

Composting Not Permitted

Their current location on Rising Sun Avenue is Bennett Compost’s third address. The first place they rented was a narrow garage on North 21st Street near Cecil B. Moore that was only 1,000 square feet. It was a modest beginning, there was no heat or hot water, but they did have cold water to clean buckets.

Next, their operations moved to Share Food Program’s headquarters on West Hunting Park Avenue in the Allegheny West neighborhood of North Philly. There they had ample indoor and outdoor space, which allowed them to do some on-site composting. The operation never got too large because, surprising as it may sound, composting is largely illegal in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania.

Before you panic and disable your tumbler full of leaves and food scraps, there are places in Pennsylvania where you are allowed to compost, and your backyard is one. You can also apply for a permit to compost if you own a farm, or have access to a rock quarry, or if you are a business or institution that is composting material generated on site. But, as it stands right now, there’s no permit for composting residential pickups.

This situation came to the attention of Nic Esposito, who was the sustainability manager at Philadelphia Parks & Recreation (PPR), when he was serving on the Solid Waste and Recycling Advisory Committee’s Organics Subcommittee.

“This was the first I had heard that [there was a] major hindrance to growth because Pennsylvania lacked an urban composting permit,” Esposito says. “Basically compost operations like [Bennett’s] were being regulated almost as if they were landfills, which is impossible to satisfy in the city.”

According to Bennett, “[Pennsylvania] doesn’t distinguish between someone who wants to do 500 tons a year … and 500 tons a day.”

Esposito began working with Marc Wilken from PPR, who had gotten the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to grant a permit for the Fairmount Park Organic Recycling Center. When he approached the DEP about getting a permit for a business like Bennett Compost, they said that they would need a test site.

Esposito realized that, given the upfront costs associated with outfitting a location for composting, this scenario would be untenable. Who would make the investments knowing that, if the permit failed to happen, you could be forced to move?

Esposito then had a unique idea. What if they could limit a company’s cost by making a trade? Esposito approached Molly Riordan, the city’s Good Food Purchasing Coordinator, and she helped him put together a contract for a cashless exchange.

The deal that was offered was free rent and the ability to compost on site in exchange for picking up organic waste from the city’s 256 recreation centers.

A request for proposal was posted, and Bennett Compost won the bid, largely because they were the right combination of big and small.

“The processing is on a small scale,” Bennett says. “So it’s not interesting to a larger company. But the collection is on a very large scale because you go to 156 locations spread all throughout the city.”

The project was derailed by the pandemic, and the loss of Nic Esposito, who was promoted to lead the Zero Litter and Waste Cabinet, only to have the position eliminated by the city’s budgetary cuts. However, the EPA has stepped in with some funding to cover the city’s shortfall, and pickups began in September at 25 recreation centers.

A Fair Deal

Bennett Compost’s mission is to make composting easy to do, but Bennett says that just as important has been their commitment to their employees.

The company now employs 16 people, 15 of which are full time. “We’ve offered opportunities for people to grow internally into more leadership roles,” Bennett says.

Take for instance, Mr. Saldia.

“Rudi is a special person. Had we hired a less competent person it might not have worked.”

When the pandemic hit, Bennett Compost offered hazard pay, raising workers’ rate from $15 per hour to $18, and they’ve made that rate stick. They also offer their employees, 85% of whom have no more than a high school diploma, healthcare and a 401K.

“We’ve taken pride in our ability as we’ve grown to offer better employment opportunities,” Bennett says. “We’ve hired people who are returning citizens [from incarceration] and who might have difficulty getting a job.”

After a dozen years in the business, Tim Bennett is no less enthusiastic than ever.

“I still think the work we do is meaningful. It’s part of what I found so attractive about it when I was starting. Not just that it was a business opportunity, but it was an opportunity to do something that I thought could have an impact in our city and in the world.

“But I also enjoy it because it’s fun to figure things out. The challenge helps me get out of bed every day and work on it.”

Just signed up with Bennett’s. It has been great.