On a walk along Cobbs Creek in West Philadelphia I inspected some old ruins. On the opposite side of the creek I could see the tall earth bank interrupted by a stone block wall, covered in some parts by crumbling concrete.

I walked to the water and found I was standing on a matching surface.

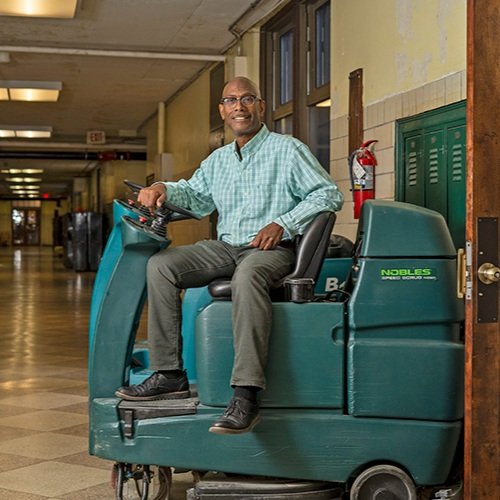

The author explores the remnants of a mill in present-day Cobbs Creek Park. Photograph by Rachael Warriner.

Obviously some structure had straddled the waterway, likely part of a mill. Looking around at the forest—dominated by box elder and silver maple on the floodplain close to the creek channel and towering oaks on the valley’s slope—it was hard to imagine a factory there.

But that wild forest is a new development, compared to the centuries of industry along the creek.

“You can make some pretty nice things that look amazing, have some benefits and do some ecosystem functions better than they are presently.”

— Dorothy Merritts, Professor of Geoscience at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster

In 1642, decades before William Penn drew up the plans for Philadelphia, Swedish colonists built a mill on Karakung, the Lenape name for Cobbs Creek, at what is now Woodland Avenue. Over the following centuries the land was cleared and dozens of mills along the creek harnessed the water’s force to run machinery that ground wheat into flour and ran saws to cut logs.

“When settlers came from Europe and arrived in this Mid-Atlantic region, they saw a landscape they were familiar with,” explains Dorothy Merritts, professor of geoscience at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster. Faced with hills and creek valleys just like in Europe, they applied the same farming and industrial techniques their people had used for centuries.

“As soon as they arrived they began building dams and mills,” she says.

The basic template for a mill includes a dam to raise the surface of the water well above the natural water level and create a pond. From there, water running out of the pond through a channel, called a “mill race,” turns a large wheel, which in turn drives the machinery.

In the early aughts, when Merritts and geochemist Robert Walter started examining creek beds in central Pennsylvania, they realized that these dams, multiplied up and down the length of creeks, had altered the valleys themselves. Left exposed by deforestation and farming, soil had washed into creeks. When that flowing water stopped at a dam, the suspended sediment dropped out. Over the centuries this sediment pollution, or “siltation,” filled in the ponds behind the mill dams.

Eventually the power that drove industry shifted to coal and then to electricity. Trees reached for the sky along the creek valleys, and mills crumbled into ruins.

Whenever the persistent force of the water breaches a dam, the liberated creek slices down through the sediments upstream until it reaches the downstream water level. Thus the landscape we see at Cobbs Creek Park—a creek cutting a deep channel through a forested floodplain—is the legacy of centuries of water-powered industry.

Every remaining dam is a time bomb. When they fail, the current carries centuries of stored silt and pollutants downstream. On Chiques Creek in Lancaster County, Merritts and Walter have been documenting the upstream effects of a 2015 dam removal.

“The channel has cut deeply down so it has about 12-foot-high banks along much of its length for almost two kilometers. It’s eroding the banks rapidly and trees are falling in,” Merritts says.

When Merritts and Walter dug down into legacy sediments built up by the old dams, they found evidence of a different world buried underneath. Instead of flat floodplains with a single deep channel, they found marshy valley floors. In these pre-colonial creeks the water spread out, meandering through multiple shallow channels.

To see what would happen if a waterway was freed from its legacy sediment, in 2011 Merritts and Walter turned back the clock at Big Spring Run in Lancaster County. Working with a large team of researchers, ecological restoration specialists and the landscape engineering firm LandStudies, they restored 3,000 feet of the stream, removing 20,000 tons of sediment.

At a cost of about $1 million per 800 meters, it wasn’t cheap, but the results were profound, with marsh-loving species such as bog turtles flourishing. The project inspired other restorations, and over the years researchers have found that the resulting marshy creeks are also more flood resilient. After heavy rain the stormwater spreads out and slows down rather than scouring the valley.

For a creek like Cobbs, Merritts notes that we can’t undo history completely. Uphill forests and fields have been replaced by our grid of streets and houses, and in the valleys other constraints such as bridges, golf courses and cemeteries limit how much area can be restored.

Nonetheless, she points to the ecosystem services (e.g. flood resilience, pollution control and wildlife habitat) provided by the marshier creeks after restoration.

“You can make some pretty nice things that look amazing, have some benefits and do some ecosystem functions better than they are presently,” Merritts says.

There is a lot more to imagine now when I walk along Cobbs Creek. I picture the area two hundred years ago, with naked hills and a valley busy with turning water wheels and the traffic of wagons hauling grain and logs in and flour and boards out.

But further back in time I can picture a quieter scene: a gentle braid of streams running through a marsh, bristling with sedges and flanked by willow and alder thickets. Maybe I’ll live to see that again.