Mulch, compost and wood chips are piled high on the concrete grounds of the Fairmount Park Organic Recycling Center in West Fairmount Park.

On a typical day at the center, city residents fill out the sign-in sheet and waiver form and collect whatever organic materials they need from the scattered piles with shovels and buckets brought from home. Residents in need of firewood can bring a chainsaw and splitter to cut the available assortment of logs, all of which come from trees harvested from parks and playgrounds managed by Philadelphia Parks & Recreation (PPR).

The center had 3,894 visits in 2020. The new Urban Wood Design Competition seeks to improve those numbers.

A partnership between PPR, the city’s Rebuild initiative and the Center for Architecture and Design, the competition was first envisioned as a way to highlight possible uses for urban wood while supporting Rebuild projects. Rebuild, which is funded by the Philadelphia Beverage Tax, invests in improving parks, recreation centers and libraries throughout the city.

Extreme weather, invasive species and aging forests have contributed to PPR’s increased wood inventory, which typically includes ash, tulip, poplar, cherry, and red and white oak.

“This is a great way of getting our wood out there to various markets.”

— Marc Wilken, Director of Business and Event Development, Philadelphia Parks & Recreation

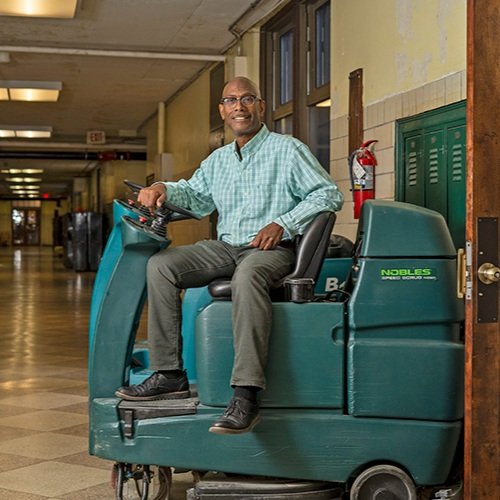

“Parks and Recreation is the hub for all wood that comes from city projects,” explains Marc Wilken, director of business and event development at PPR. “Whether it comes from the Philadelphia Streets Department, the Philadelphia Water Department or Parks and Recreation, we are responsible for managing it.”

PPR has always turned wood into mulch and wood chips, but in recent years has begun milling wood into dimensional lumber for various city projects. Between 2016 and 2017, PPR worked with a local sawyer to generate more than 1,700 board feet of lumber. This lumber has been used for garden beds and bridges, as well as cubbies and bookshelves for recreation centers.

“We’re averaging about 1,000 tons of logs coming in per year. It certainly is more than what it was a few years ago,” Wilken says.

PPR first approached Rebuild to brainstorm a way to make use of the extra wood. After some discussion, they brought in the Center for Architecture and Design to manage a competition and interact directly with designers. The partnering groups have centered the competition around the pool at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Recreation Center, which is in need of new furniture.

Wilken’s hand on a tree trunk.

“We said, ‘Where are some Rebuild sites that aren’t getting a total renovation?’ We ended up going with pool furniture because many pools are looking for additional amenities. MLK has a large pool deck, so it can accommodate furniture. It was also open this year, so our designers can observe the pool and talk with community members,” says Rebecca Johnson, executive director of the Center for Architecture and Design.

PPR staff were inspired by the Baltimore Wood Project, and participated in the Urban Wood Academy, held in Baltimore in 2018, that brought together 18 participants from 10 states. The academy offered discussions and advice for other municipalities interested in creating local economies from urban wood, either fresh-cut from felled trees or from deconstructed buildings.

PPR also recently issued a request for proposal to have a private firm operate a lumberyard out of the organic recycling center. A lumberyard would prepare, sort and sell the wood; sales would help support the urban forests of Philadelphia.

“The idea with the lumberyard, or any wood we sell, is about putting some of the proceeds into our forest management and natural lands,” Wilken says.

“The decision to go from a dumpyard to a sort yard is a huge strategic difference. If those materials could be put in a place where they could be aggregated and sorted, [there] wouldn’t be wasted materials. People who buy these materials can come in and say, ‘I want white oak.’ If you don’t have those sorted, it’s just a big pile of sticks,” says Mike Galvin, registered consulting arborist at SavATree Consulting Group.

The Urban Wood Design Competition was launched in July with a call for submissions for designs or fabrication using wood from the organic recycling center. Participants can be an individual, team or firm.

“This initiative doesn’t just add a fantastic asset to one of our project sites. It also energizes Philly’s local designers and fabricators,” Raymond Smeriglio, director of communications at Rebuild, says.

Participants’ designs must be predominantly wood, last outdoors in all weather, fit community and outdoor pool deck facility needs and have reasonable production costs so the model can be replicated.

“The wood will have to be treated. They’ll have to think about joinery, [which] allows wood to expand and contract. They’ll have to explain how this [furniture] can live outside,” Johnson explains.

Final submissions will be due November 1. Finalists will be chosen by November 30. In 2022, a sawyer will mill for all prototypes at the organic recycling center, and they’ll be exhibited at the recreation center pool through the summer of 2022. A winner will be announced in September 2022.

“This is a great way of getting our wood out there to various markets,” says Wilken. “Raising awareness of it to the local design and architecture community and inspiring folks to think about our wood at different scales.”