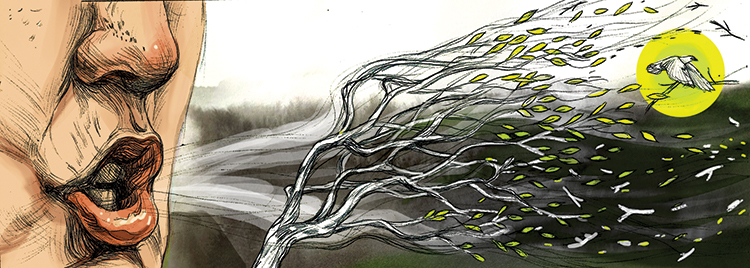

Illustration by Nicholas Massarelli

You Can’t Buy Health

by Jerry Silberman

Question: What does it mean for me to be healthy?

The Right Question: Can I be healthy without a healthy community?

I suspect that we have an inborn ability to recognize good health in another person when we see it—and that our perception of beauty rests substantially on a foundation of recognizing good health. It is precisely that innate ability, rooted in evolution and our tribal history as a species, that should alert us to a critical aspect of health and wellness that we often overlook: our need for community.

But let’s start with good food and clean air and water first.

Initially, access to clean water, fresh air, sunlight and food were our only requirements. And although humans evolved in a subtropical environment, our ability to supplement our inborn temperature regulation (with, initially, the skins of animals unlucky enough to meet the end of our spear points) allowed us to spread over the globe.

In different environments, we developed vastly different diets to get us the same nutrients we needed to promote health. We were exposed daily to competing organisms in our environment and were required to collect the means of our sustenance. Hence, we developed our senses, muscles and immune systems.

In contrast to the conditions that allowed us to flourish, modern, high-tech society presents us with significant challenges.

The mechanization of food and work in general challenges our muscular development and physical health, leading many to resort to working out in gyms rather than leading a generally active life.

The introduction of chemical toxins our bodies have no ability to process—and isolation from the natural microorganisms that stimulate immune system development—challenges our metabolic defenses, and may lie behind the explosion of chronic metabolic and autoimmune diseases.

Our diets have also been compromised. The rise of processed foods, which strip out micronutrients and oversupply elements that stimulate the appetite, has been linked to obesity and any number of chronic conditions including diabetes and heart disease.

Crops have been genetically modified primarily for the purpose of introducing resistance to herbicides. That has contributed to a vast increase in the release of toxins into the environment, most notoriously glyphosate, a probable carcinogen.

These huge structural conditions—industrial agriculture and the processed food industry, widespread pollution and other chemical intrusions—conspire to make us unhealthy.

But the solution, in my view, is not to embrace another commodity, in the form of the latest silver-bullet diet supplements, additional relationships mediated by cash, or a practitioner of some newly invented scheme to rejuvenate my body. (Note: I firmly believe that medical traditions outside the modern industry of Western medicine, such as acupuncture and herbal medicine, have a lot to offer, in the proper context.)

First, we should eat well, paying attention to where and how our food was produced, as well as its composition. Limiting and reducing our load of environmental toxins is clearly possible. Second, let’s keep our tribal roots in mind.

Honoring that structure is crucial to the “mental and social well-being” aspect of health, which the World Health Organization cites in its definition of a healthy human. The feedback loops among mental, social and physical health are real, but only partly understood.

Some researchers in British Medical Journal have recently suggested an even more inclusive and dynamic definition, which includes the concept of resilience. “Health is the level of functional and metabolic efficiency of a living organism. In humans it is the ability of individuals or communities to adapt and self-manage when facing physical, mental or social challenges.”

I like this framework, because it gets at the idea that maintaining good health requires access to the environmental conditions in which we evolved—including community.

While a huge crowd means security for a wildebeest or a caribou, it creates anxiety for a human. At the same time, we are not tigers—solitary creatures except for rare bouts of sex or parenthood.

Unfortunately, many of us—as a matter of defense or survival—tend toward the tiger mode, with few or fleeting serious relations of mutual dependence. These relations of mutual dependence among a diverse group of human beings who meet each other’s needs in distinct but complementary ways is what makes a tribe.

A tribe is a community, and a community a tribe. No matter what you call it, it’s part of our nature, and critical to our well-being.

Once again, our modern society is getting in the way. Overcrowding, alienation from tribal or community structure, and the experience of money mediating much of our human interaction challenges our social and mental well-being on many levels.

So it’s important to embed yourself in a real community; people you need and trust, who will be there for you, as you will be for them. The foundation of this community can be your family, your neighborhood, your religious institution or many others less clearly named. Reduce your consumption of goods and services that mediate between you and others (eating right will take a bigger chunk of your disposable income, and it’s worth it). Shut off the noise of social media and the big screen and read your favorite books out loud to each other on those long winter nights.

Jerry Silberman is a cranky environmentalist and union negotiator who likes to ask the right question and is no stranger to compromise.