A year ago, advocates of solar energy across Pennsylvania were flying high. Democratic state Rep. Elizabeth Fiedler, whose South Philly district stretches from Pat’s King of Steaks to Lincoln Financial Field, had just pulled off a political Hail Mary: successfully shepherding a clean energy bill through the gridlocked State Capitol. Titled Solar for Schools, the legislation promised to provide $25 million dollars for schools to install solar arrays across the commonwealth.

A year later, the sentiment is decidedly mixed. In a state budget bill approved by lawmakers in November — after an impasse that spanned more than four months — Solar for Schools was renewed for another $25 million. That appears to be a vote of confidence by lawmakers after a successful first year. Environmental nonprofit PennEnvironment calculates that the program received 88 applications to install solar at schools, totaling $88 million in requested funds, more than three times what it was equipped to pay out. Ultimately, 73 applicants across 24 counties received about $23 million, including about $2.3 million for projects at seven schools in Philadelphia, with additional projects in the suburbs.

The ability of a school to generate their own electricity, to provide them with that energy, freedom and independence, and also that return on investment, is really exciting for me as a parent and lawmaker.”

— Elizabeth Fiedler, State Representative

“I’m proud of the first year,” Fiedler, who chairs the state House Energy Committee, said in a late October interview. “The ability of a school to generate their own electricity, to provide them with that energy, freedom and independence, and also that return on investment, is really exciting for me as a parent and lawmaker.”

This year’s state budget also cleared the way for the state to use $156 million in federal Solar for All funding, which would install rooftop solar in low-income areas in Pennsylvania — another apparent boost for heliophiles in the state and city.

But upon closer inspection, the outlook isn’t quite as sunny. Renewable energy advocates say the Solar for Schools funding is only a sliver of a silver lining in the increasingly dark clouds gathering over Pennsylvania’s state solar policies. Flora Cardoni, deputy director of PennEnvironment, says that the funding for the twin solar programs was overshadowed by Democratic leadership’s decision to pull Pennsylvania out of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), an interstate carbon cap-and-trade program. That initiative could have provided more than a billion dollars of clean energy funding, Cardoni says, while pushing the state’s energy mix away from fossil fuels and toward renewables.

“We would need to get a lot of policies like [the solar bills] to make up for RGGI in terms of carbon reduction,” Cardoni says.

Adding to the headwinds are changes at the federal level. Passed earlier this year, President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill took a wrecking ball to former President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and initiated steep rollbacks of federal incentives for renewables. Advocates say that many Pennsylvania school districts receiving Solar for Schools grant money had also planned to use federal incentives to pay for as much as 30% to 50% of the costs of their projects, stacking incentives to make solar as affordable as possible. But the sunsetting of those provisions has impacted the calculus.

Ron Celentano, president of the Pennsylvania Solar & Storage Industries Association, lives just outside Philadelphia and acts as a consultant to several school districts. He says he has yet to hear of any district scrapping its solar plans. But he says some have begun asking questions, and he predicts it may happen. Schools have until July 4 to begin construction in order to get a four-year runway to finish projects and obtain federal credits. But that’s a tight timeline to go through design, permitting and securing the services of a contractor when a statewide rush to start construction is underway. Miss the July 4 deadline, and they’ll need to fully complete construction by the end of 2027 to qualify.

“There’s a little bit of concern to some of these schools: Are we going to make it?” Celentano says.

The issue has ramifications in Philadelphia, where four School District of Philadelphia buildings were awarded grants in the first year: Andrew Hamilton School, Murrell Dobbins Career and Technical Education High School, Northeast Community Propel Academy and W. B. Saul High School. The Community College of Philadelphia also received a pair of grants, along with one for the Universal Audenried Charter High School. Altogether, the grants were valued at $2.28 million, with about half going to the district.

Whether or not the district has recalculated its plans or holds concerns about the looming deadlines is unclear. Brett Schaeffer, special director of policy in the Office of the Superintendent, is the district’s point person on the program. He referred Grid to a May 2025 press release, published prior to passage of the Big Beautiful Bill, that stated Solar for Schools funding will cover “up to 50 percent of construction costs for solar energy projects” at the district buildings.

“Clean energy rebates and incentives will further discount project installation costs, with District funds covering the remainder,” it added.

But asked in early November about the current status, Shaeffer said only that “the projects won’t begin until the spring.” Principals of several of the recipient schools also did not respond to requests for information. The district did not respond to inquiries about the specifics of how it’s navigating the changes.

“The School District is continuing its work on the four solar projects it received state grant funding for, and is excited that the state recently reauthorized the Solar for Schools grant program for a second year,” spokesperson Christina Clark wrote in a brief email.

The $156 million in Solar for All funding faces the same challenges, and then some. Although state lawmakers have now approved use of the Biden-era federal funding, the actual money remains tied up in the court system after the Trump administration attempted to cancel it.

“An important tool”

Katie Bartolotta, vice president of policy and strategic partnerships for the Philadelphia Energy Authority (PEA), a quasi-governmental entity working on clean energy development, presents an optimistic outlook. She says the PEA consulted with the district on its Solar for Schools applications as part of a long-running relationship between her group and the City. She believes meeting the construction deadlines for federal incentives is “completely doable.”

Ben Block, communications manager for PEA, adds that the school district has a “long track record of implementing successful clean energy projects,” pointing toward what it calculates is about $250 million in energy efficiency upgrades at 24 schools in recent years.

Statewide, advocates have touted Solar for Schools’ potential to break through partisan battle lines in rural counties, where there’s plenty of space for large ground-level arrays. Indeed, one of the program’s most vocal cheerleaders is the Carlisle Area School District, a small town district in a region that went for Trump in 2024.

But Bartolotta says the task to install solar at schools is trickier in Philadelphia, where space is at a premium and City and school district administrators have to take into account aging facilities.

“The one thing [Solar for Schools] didn’t have was funding for enabling upgrades: roof repair, electrical upgrades, anything like that,” Bartolotta says.

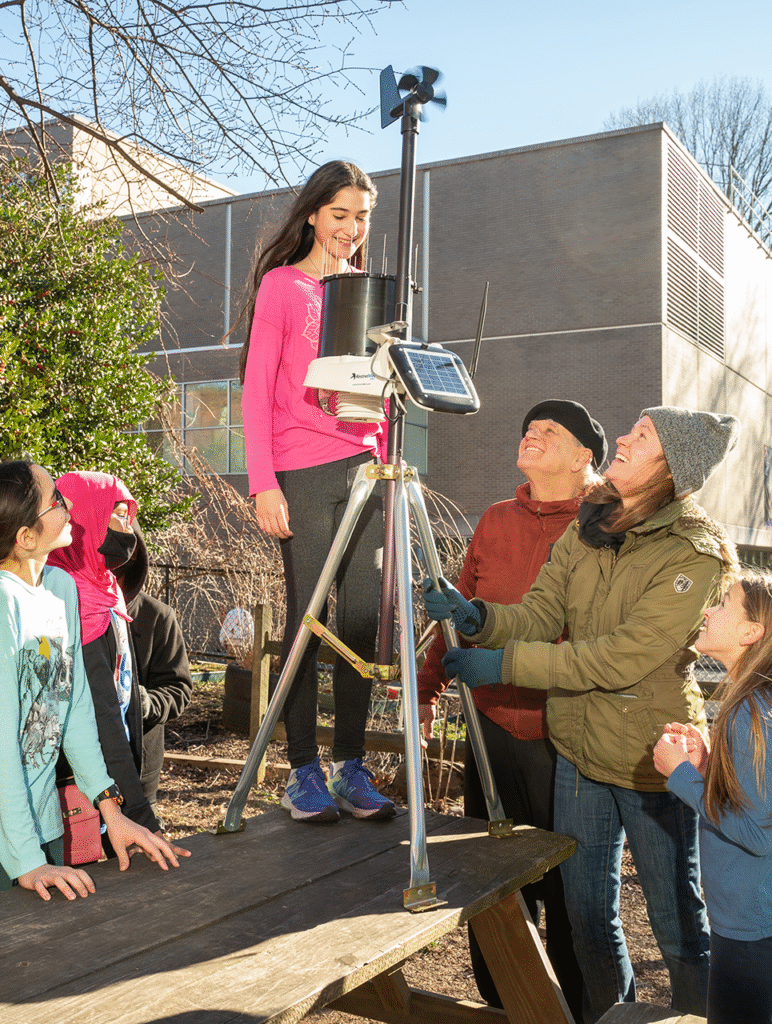

So, planners had to get choosy, identifying buildings that had the spatial and physical capacity for solar. They encountered a few happy accidents along the way, Bartolotta says: Dobbins is a career and technical school in North Philadelphia with a building trades program that could benefit from a first-hand look at solar arrays, and Hamilton, a K-8 in Cobbs Creek, has long been in talks with the University of Pennsylvania on going solar.

Assuming the projects move forward, Bartolotta sees them as a critical step in the district’s efforts to shift to sourcing clean energy. She’s aware of only a handful of buildings in the district’s inventory of more than 300 that already have solar, and saw Solar for Schools as “an important tool” to move the district further along the learning curve, especially if there were to be renewing pots of federal and state money.

“We worked with their capital team to say, ‘Hey, this is just the first round. This is a chance to establish and see what this looks like’,” Bartolotta says. “And once folks start putting their projects into service and start to see the savings they can realize on an annual basis, I imagine support could grow.”

But there’s yet another challenge to schools to bring their systems online quickly enough to realize the expiring federal benefits. Celentano says there are application delays at Pennsylvania electric utilities, such as PECO, for those seeking to connect rooftop solar and other similarly-sized ground arrays to the grid. PECO did not respond to requests for comment, but other utilities across the state, such as PPL, have said their queues can take as long as three years to clear for complex projects, the kind of delay that could risk some Solar for Schools recipients missing federal incentive deadlines.

Pennsylvania Utility Commission spokesperson Nils Hagen-Frederiksen confirmed that applications for some arrays are taking time to process, given cost and safety considerations, along with an application rush ahead of federal deadlines.

“The Commission continues to review interconnection-related issues statewide to ensure that the process remains timely, transparent, and fair for all customers,” Hagen-Frederiksen says.

If the state can fix those things — if they’re willing to — then we can be moving this forward without a lot of other action.”

— Sharon Pilla, Pennsylvania Solar Center

Sharon Pillar, executive director of the nonprofit Pennsylvania Solar Center, says the issue is a focal point for solar advocates who have been disappointed by the legislature and its recent budget deal. In early November, the advocacy group Vote Solar launched a petition asking the PUC to do more to facilitate rooftop solar, such as requiring transparency into utilities’ solar connection queues and creating “clear, enforceable timelines” for applications.

“If the state can fix those things — if they’re willing to — then we can be moving this forward without a lot of other action,” Pillar said.

This story contains reporting that first appeared in Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission.

This special section is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This special section is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit