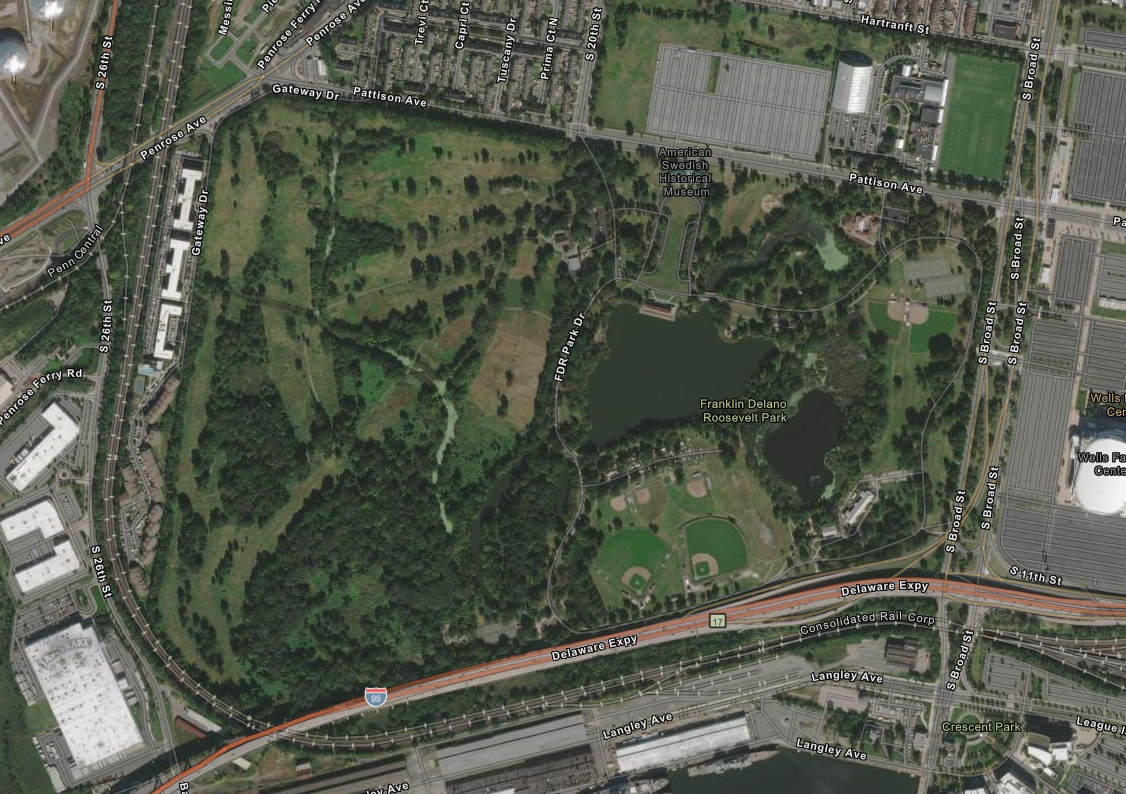

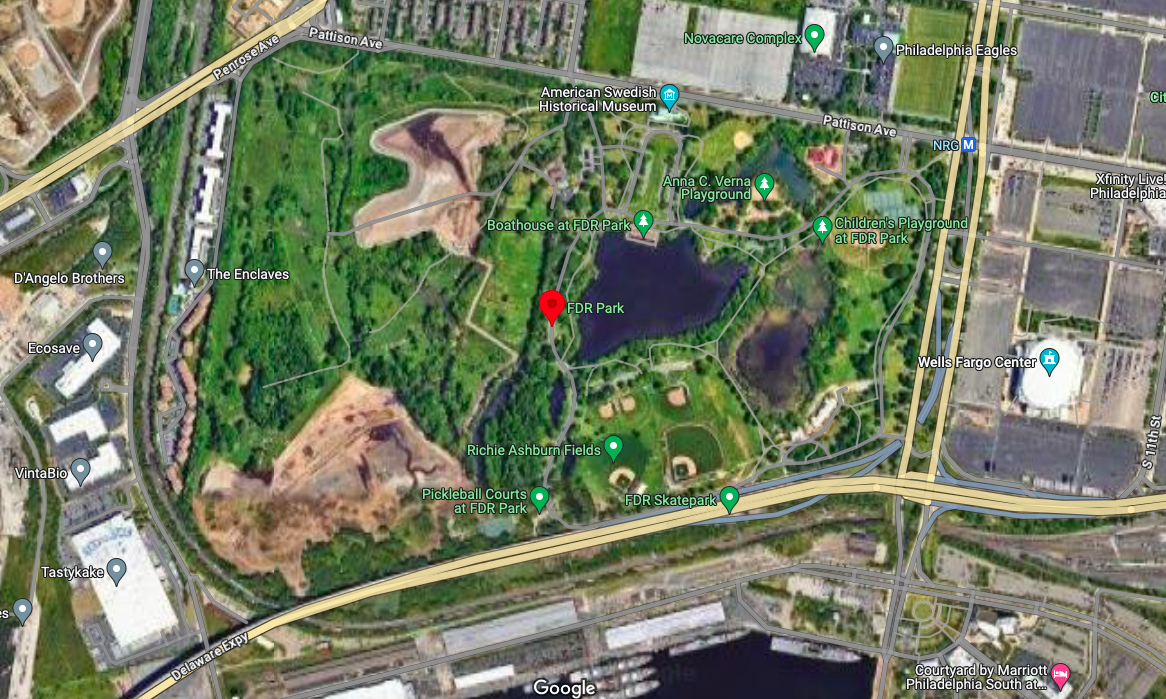

I am standing in the Meadows, at the southwest corner of FDR Park, in a 33-acre mud pit roughly the size of eleven city blocks. Where once stood a mature woodland, now stands a vast strip of nothing—with an unimpeded view of I-95. The pit is prickled with hundreds of almost indiscernible, twiggy saplings. I squat to inspect their plastic yellow tags, still attached from the nursery. Standing beside me is Scott Quitel, professor of ecology and founder of the LandHealth Institute. We are in the heart of the so-called “wetland restoration” project, the centerpiece of what the Fairmount Park Conservancy has been advertising as the “ecological core” of their plan for the park. Quitel takes a panorama shot of the massive mud pit with his phone, then shakes his head. “This is embarrassing. This is shameful. If they’re calling this some kind of ecological zone, that’s just flat out wrong.”

He looks behind him to where two wooden swings once dangled on the branch of a grand heritage pine, and then back to the hole in the landscape. This was funded by the Philadelphia Airport after it was required to replace wetlands it bulldozed southwest of here. “It’s bad enough that they do something bad [like clearcutting heritage trees], but then on top of that … they say, ‘it’s really for your own good’ … it’s insulting.” Even if it succeeds, Quitel says, in decades, “when we’re both dead,” and some of the trees have grown back to the size of the trees that once stood here, “it won’t be worth it, because of what was lost.”

I myself thought this wetland restoration was going to be “the good part” of the FDR Park Plan — that perhaps invasive plants would be individually, painstakingly removed and other native plants put in their place. I even described the project as “admirable” in my 2022 piece on the Meadows, but when the cutting commenced along I-95, it was immediately clear that nothing would be saved — not the tulip poplars, the maples or the bald cypresses … not even the row of heritage pines. When I saw the dust bowl the bulldozers left behind, I realized the ecological claims behind the plan were as hollow as the scar they had produced.

“You can’t turn a hamburger back into a cow,” Kyla Bennett tells me. Bennett is the science policy advisor for Public Employers for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), and she worked as an EPA wetland permit reviewer for ten years. “It makes no sense to take an intact upland system and turn it into wetland … if they’re getting rid of the native species as well, that’s just stupid.”

The Fairmount Park Conservancy, who is overseeing the project, will use the soil scooped out of the airport mitigation project to raise the ground level and install infrastructure along the edges of the park. Allison Schapker, chief projects officer at the conservancy, calls this piling of soil along the urban perimeter “thickening the bathtub edge.” The conservancy claims this excavation and remolding of the landscape will address water issues. The park lies within the 100-year floodplain and frequently floods. She defended the 2022 clearcutting in a webinar for the Consortium for Climate Risk in the Urban Northeast, saying: “The addition of 7,000 native trees on a site that was full of construction debris and Siberian elm, that’s a net gain.” Schapker failed to mention that the wetland mitigation feasibility study identified fourteen native species of trees in the mature forest that the airport felled, and that many of those trees were among the largest and oldest in the entire park.

The conservancy’s 33-acre wetland project signifies a net loss for Philadelphia’s green spaces. The airport deal, which was promoted as “the single greatest addition to the park’s water bodies since the original lakes and lagoons were constructed,” enabled the airport to demolish 120 acres in their surrounding floodplain, which could increase flooding in Eastwick. And regardless of how native or non-native the forest once was along the highway, even 33 acres of non-natives would be preferable to what exists today. A non-native forest would, at the very least, filter the pollution and noise coming from the highway, sequester carbon, mitigate stormwater runoff, and give us shade and air to breathe. And though I hope that the new plants succeed and one day supply some relief for the inhabitants of the airport wetland that was destroyed, at the moment, the new FDR “wetland” has nothing to offer but heartbreak.

This empty basin along I-95 is just the beginning of the clearcutting scheduled for FDR Park. According to the bid drawings for the next phase of the plan, an additional 432 trees will be cut, including 63 heritage trees. This does not include the phases that will follow.

At a moment when existing athletic fields across the city are in need of repair, the conservancy’s master plan would plough $100 million into a suite of new, artificial turf fields in South Philadelphia. Where the heritage maples and river birches once stood at the entrance to the Meadows, plastic grass will be installed. “The plan doesn’t seem to have any ecological sensitivity to what is there,” says Kat Kendon, co-founder of a new organization called EnviroPhilly. “The designers perceive the land as a completely blank slate that they can terraform to their will.” But in fact the remaining land is not a blank slate. It is teeming with life and full of value, including wetlands along the park’s tidal creeks. Wetlands are second only to coral reefs in terms of their biodiversity value. They support 40% of the world’s plant and animal species — including us.

As a forest therapy guide, I have been leading group walks in the Meadows since the pandemic. As I take people through the remaining trails to survey what the current plan will erase, I find myself enthralled by the beauty of the wildlife that has found a home in this abandoned golf course, and equally horrified at the rapidity with which it is being destroyed. So often, I have paused to gasp at a blue heron so close I could count the toes on his feet; at the tail of a hawk made ruddier by the melting sun; at a bald eagle startled from his perch — an eagle that will only nest in the tallest trees.

“When a two hundred acre golf course closes, you’ve basically been given the biggest gift ever,” says Quitel. “It should have been returned to the park and been made into passive recreational space.”

Philadelphia is one of the poorest big cities in the country. Is spending $100 million on a set of plastic fields precariously perched on the “bathtub edge” wise? Shouldn’t the money be spent on maintaining and upgrading the fields that we already have? If we need more fields, shouldn’t we put them in neighborhoods that are already “high and dry” — neighborhoods where kids live, not a 15 minute hike from the last stop on the Broad Street line? If we care about our kids, shouldn’t our fields be free of carcinogens and endocrine disruptors, not carpeted with toxic plastic that has been continually cited as an environmental and public health hazard?

The Fairmount Park Conservancy claims they can source permeable, PFAS-free turf, but when I spoke to former wetland permitter Bennett, she said, this product does not exist. Bennett was the first scientist to discover PFAS in artificial turf in 2019 — the same year the master plan was released. It’s likely PFAS was not considered a cause for concern during the development of the plan, Bennett informed me, but now they should know better. (Micro-plastic pollution in the waterways should have always been a concern.)

“There are no brands [of artificial turf] that are PFAS-free. That is just a lie. And you can call it that, you can quote me on that. It is a lie. They do not exist.” In addition, “you’re talking about 16 fields, that’s an awful lot of PFAS … And that includes PFOS and PFOA, which are gonna be regulated any day now by the EPA. So, they’re really setting themselves up for a big problem,” such as lawsuits. This “massive contamination will cost millions and millions of dollars to clean up.”

States and municipalities are already issuing bans. The mayor of Boston has banned any new installation of sythetic turf, and last year the California legislature attempted to ban it as well. Though the conservancy insists that they have identified next-generation plastic turf for the project, they have yet to provide a verifiable lab report from a PFAS-free vendor. And let us remember that PFAS-free does not mean toxin-free. The turf companies are scrambling for a new recipe to outpace the bans, and they will turn to untested novel compounds — chemicals which should not be tested on children. When BPA was found to be a potent endocrine disruptor, some companies switched over to BPS, which was then found to have similar effects. The only toxic-free turf you can depend upon is grass.

Setting aside the issue of toxic turf, there remains another, equally-compelling reason why the plan should be paused. FDR Park is wedged right between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers in a snaky tangle of streams. The only reason the park is not a marsh is because the tidal gate blocks the river at high tide and because it’s been filled in several times over the last few centuries. The Fairmount Park Conservancy and the City are trying to engineer what wants to be a freshwater estuary into “high and dry” athletic fields. The plan argues that hundreds of trees need to be cut down to do this engineering. The conservancy can fill it in and raise the level again now, but we should know that in time we’ll be right back where we started. It’s an urban estuary that will continue to return to its alluvial origins, to sink and settle, to respond to the pull of the ocean, and sooner or later the water will win. Instead of fighting the land, what if we surrendered? What if we embraced this land for what it is — a historical wetland — rather than trying to wrench it into what we’d like it to be? It might be too wet in the Meadows to play golf or soccer, but with some boardwalks installed it wouldn’t be too wet to serve as a recreational area for hiking and biking. “You don’t expect intelligent people to think about putting soccer fields in a wetland. It’s a non-starter,” says Quitel, “and chances are this place is gonna get walloped; it doesn’t matter how much infrastructure they put in.”

I reached out to Philadelphia Parks & Recreation to say that I understood clearcutting was being partially justified on the basis of sea level rise and to ask how many feet exactly the master plan was adjusting for. Communications director Charlotte Merrick responded: “There has not been any clearcutting at FDR Park. Trees have been selectively removed to complete ecological restoration projects, remove invasive species, or provide high-quality recreational amenities desperately needed by South Philadelphia’s young people.”

Future sea level rise may be debatable, but the clearcutting at FDR is not.

Selective removal? How can the tree removal qualify as selective when not one tree was saved or selected for in the 50 acres that were cleared, including heritage-sized trees of native origin?

Philadelphia suffered severe ecological degradation at Cobbs Creek in February 2022. Bethany Tiegen, Philadelphia Mycology Club founder and member of the Cobbs Creek Ambassadors, recounts how massive cutting was sold to the neighborhood under the guise of wetland restoration, without any clear communication about what the so-called restoration would destroy. “At no point was anyone talking about the fact that they were going to be cutting down a large number of trees.” People woke up in the morning to the sound of saws, and they looked out of their windows in horror as one tree after another fell to the ground. Teigen maintains that Parks & Rec is what ties the loss of these two tree canopies together. “The golfing foundation can only do this to the city one time, but the City is allowing this to happen all over the city.”

In 2022, City Councilmember Katherine Gilmore Richardson sponsored a new tree bill. It was an attempt to strengthen existing protections and stave off further tree loss in Philly, where the canopy shrunk by 6% between the years 2008 and 2018, “the equivalent of 1,000 football fields of trees.” In the case of the Meadows it will literally be football fields standing where the trees once stood. Now anyone who wants to chop down trees in Philly will have to notify an environmental advisory board and engage with an RCO (registered community organization). If the developers can demonstrate to the community and the board that keeping the trees on site is “impracticable” they will now be required to pay into a tree fund or plant new trees equal to the total DBH of trunks they remove. For example, ten little trees to replace one big tree.

“Katherine Gilmore Richardson meant well,” says Keith Russell, of Audubon Mid-Atlantic, about the tree replacement stipulations in the plan, “but what they’re doing is a non-equivalency. It’s like saying a person who is sixty years old is the equivalent of six ten-year-olds.” Even though a stated goal of the new Philly Tree Plan is to “protect the existing urban forest,” the removal of our existing canopy continues to be allowed. When I asked Erica Smith Fichman, acting manager of urban forestry at Parks & Rec if this means that the tree bill has no teeth, and needs to be strengthened, she answered: “This is the first of what I hope will be many tree bills … this is a first step.”

Failures in local policy have global consequences. Trees are the architects of our atmosphere, and we are living in an atmospheric crisis of epic proportions. Many activists are calling this the decisive decade—the decade in which we will turn a corner and prevent the worst effects of climate change, or the decade where we will ensure irrevocable consequences. At this stage, clearcutting mature canopy and replacing it with toxic plastic fields should be illegal. If park leaders aren’t even acknowledging clearcutting or defending trees on public land, what kind of precedent does that set for the average Philly developer or private owner?

The United Nations estimates that deforestation and forest degradation accounts for 11% of CO2 emissions globally. All trees remove carbon from the air, but some more than others. If the new replacements survive at FDR Park, it will take decades before the saplings sequester as much carbon as the mature trees they’ve replaced. The average life expectancy of a street tree in Philly is 10 to 20 years. Many trees die in their first year of planting due to transplant shock, lack of watering and poor soil. “Planting new trees is not a direct exchange of carbon,” says land-monitoring expert Adia Bey. “It’s more like a hope or a prayer for equal carbon sequestration in the future.” Can we afford to bet our future on a hope and a prayer?

Our veteran trees have powers that younger trees simply don’t have. Oak trees usually take about thirty years to produce their first acorns. Cavities formed by heart-rot fungi are centuries in the making. These fungi catalyze biodiversity by creating the cavities which woodpeckers, raccoon babies, and owl mothers depend upon. A hole just large enough to support a honey bee nest can take 50 to 100 years to develop. Lichen grow at the extremely slow rate of 1 millimeter per year. Two dangling cicada shells on a heritage maple slated for demolition indicate the existence of nymphs feeding on the roots underground. But if the tree dies, so will they.

Trees, like fine wines, grow more valuable with age. They weave themselves not only into our lives, but a history that expands before and beyond us. In many cultures trees of a certain seniority are revered as deities. A heritage tree is not just an older tree or a bigger tree: it is a community, an entire ecosystem of innumerable, inter-related critters to which the tree is home. If you could look below what appears to be a stand of separate trees, each engaged in their own battle to survive, you would reveal something more akin to a single organism, connected by a vast network of nutrient exchange. A young sapling may have two to six feet of root length, while the root system of a mature oak may be a hundred miles long. In other words, when you cut down a single old tree, you rip up a world.

Only 6% of trees in Philadelphia are designated as heritage trees. There is a congregation of forty of these veterans, all slated for demolition, scattered around the entrance to the Meadows, a rare community. They stand in an area often referred to as “the picnic grove” — a beloved spot for birthday parties, music festivals, family cookouts and holiday celebrations. In an attempt to restore some of the original 1914 design, the master plan will clear away athletic fields bordering Broad Street to create a “great lawn,” while the picnic grove in the Meadows and its existing great lawn will be destroyed to make way for fields. This amounts to an ecologically devastating fidelity to an outdated map.

Those designers are dead, argues Avigail Milder, a frequent visitor to the picnic grove. “Why don’t they keep the fields that exist over there, and leave us our existing great lawn full of great trees?”

Much has been lost, but there is still time to change course. Milder is not the only one who sees room for improvement in the plan. Quitel says the massive hill, formed from the excavation debris, could easily be planted over with drought-resistant native grasses and left as is. The recent snow revealed its potential as a great sledding hill. Philadelphians have lots of constructive ideas if Philly leaders can make space to hear and consider them. Thanks to the tree bill, there are at least two opportunities to speak up this month: a community meeting at City Life Church on February 13 at 6 p.m. and a virtual zoning meeting on February 21 at 2 p.m. We can always write to our Council members. Whether officials will choose to implement what people have to say is another matter entirely. At a pro-fields rally on Jan 27, Mayor Cherelle Parker, flanked by children in sports jerseys, repeated again that she’d made a promise to make the city of Philadelphia “the safest, cleanest, greenest city in the nation” — and then endorsed 16 athletic fields worth of plastic grass.