Chris Deatrick’s girlfriend called him early in the morning on Thursday, September 2, 2021, pleading with him to leave his apartment at the Apex on Venice Island in Manayunk.

Deatrick didn’t think about safety issues when he first moved to the Apex, because on most days the Schuylkill River is slow, muddy and meandering, and the Manayunk Canal on the other side is still and shallow. “It’s a river,” he says. “You don’t think about it.”

In the first days of September 2021, however, the remnants of Hurricane Ida were just passing through Philadelphia, and the Schuylkill was rising rapidly. The day before, Deatrick and other Apex residents had received an email from JRK Property Holdings, the building’s management company, with a rather mild warning. “They just sent an email and told us it might be a good idea to move our cars,” he says.

McKayla McLaughlin and Quinte Scott got the same email. In June they and their dog had moved into one of the town houses managed by the same company, just downstream from the apartment building. Two weeks before Ida hit, McLaughlin had given birth to their son. Scott moved their two cars up the island a bit. He says the email did not make clear the need to move cars to higher ground on the mainland. They didn’t realize how vulnerable their new home was to flooding.

Deatrick was reluctant to leave at first. “How could it be as bad as last time?” he recalls asking, alluding to Tropical Storm Isaias, which had flooded the apartments the year before. But his girlfriend kept calling until he had packed a bag and left for her place, nearby but on much higher ground.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June through November, and it peaks in early September.

Hurricane Ida first made landfall in Louisiana as a dangerous Category 4 hurricane on August 29, 2021, on the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic landfall 16 years prior. It continued its journey northeastward, eventually joining forces with another low-pressure system moving through the Ohio Valley and crippling parts of the Mid-Atlantic and New England with heavy rain and tornadoes. Over a foot of rain fell in under 12 hours in some parts of the Schuylkill watershed, and several river monitoring stations in and around Philadelphia recorded their highest ever measurements.

Apex residents reported that, aside from the message to move cars, building management issued no additional warnings as the Schuylkill rose. Unsuspecting residents went to sleep that Wednesday night with no inkling that they’d be trapped by the following morning.

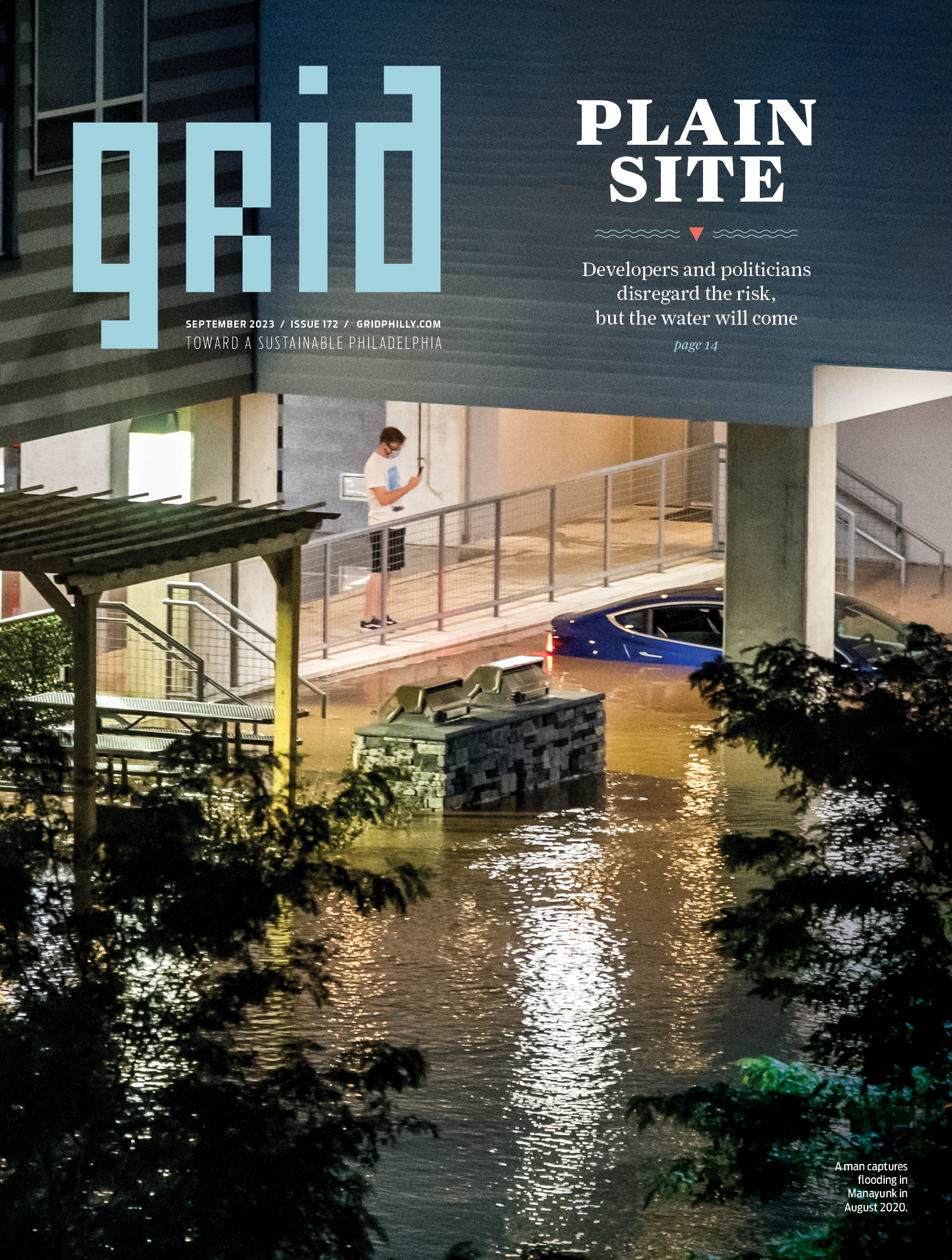

Wesley Cherry, another former resident of the Apex, says that he could see the water rising by the minute on the night of September 1, quickly filling the parking garage and East Flat Rock Road before getting into and eventually fully submerging the complex’s first floor.

In the early hours of the morning, the residents woke up, either from car alarms, panicked phone calls from loved ones or a knock at their door from the fire department. Cherry describes looking out the window at submerged, short-circuiting cars, lights flashing and windshield wipers churning as if they were being operated by ghosts.

Several people who could not get to the emergency exit were rescued by boat, as was the case after Isaias in 2020, after a heavy rainfall in May 2014 and after Tropical Storm Nicole in September 2010.

I had to hand my baby out through the second floor window.”

— Quinte Scott, former Venice Island resident

Scott said water had started seeping into the first floor by around 10 a.m. Three hours later the water had reached the second floor. “We got rescued after the fourth hour. Water was still pouring in, up to our knees on the second floor,” Scott says. The family and their dog were rescued through a window on their second floor. “The baby was two weeks old … I had to hand my baby out through the second floor window. McKayla had had a C-section. This was a sensitive time.”

The apex’s power went out in the middle of the night, and it didn’t come back on for over two weeks. Management provided no guidance or assistance for temporary housing. Once the power returned, management emailed residents to let them know that they could come back, but residents discovered a host of issues. Deatrick found that his apartment, along with around 15 others, had been broken into. No one had received any prior notice of the robberies, and Deatrick had no way to fully close or lock his door until the busted deadbolt was fixed.

The gas in the building wasn’t working either. When Deatrick reached out to management to complain about the break-ins and the non-functional gas, he was basically told that he’d returned to a disaster zone and shouldn’t have expected things to be back to normal after just a couple weeks.

We lost almost everything in this flood.”

— McKayla McLaughlin, former Venice Island resident

At McLaughlin and Scott’s town house, the floodwater ruined everything that they had on the first floor. “We lost almost everything in this flood. All my work stuff,” says McLaughlin, who is an esthetician. “We hadn’t unpacked completely.”

They were able to salvage some clothes but lost furniture, appliances, sneakers and much of their clothing. The floodwater also destroyed gifts from their recent baby shower. “Everything for the baby got ruined,” Scott says.

They also lost their two cars. After the flood a towing company notified them that it had their two cars and would only return them for $6,000. Figuring the cars were ruined by the floodwater, they chose not to pay to recover them.

Scott and McLaughlin reported that the building management offered no help in finding temporary housing immediately after the flood. Rather than stay at a local high school that had been converted into an emergency shelter, they decided to pay out of pocket for a hotel. “I have a newborn,” Scott says. “I’m not sleeping in a gymnasium.” He says ultimately the couple spent about $6,000 on the hotel and a rental car as they sorted out their next steps.

Manayunk is one of the most flood-prone neighborhoods in Philadelphia, and that flooding has been exacerbated by both climate change and local and upstream development.

Venice Island sits between the Schuylkill River and the Manayunk Canal, and residential development of the island was long prohibited due to its positioning in the floodway of the Schuylkill.

Sooner or later somebody is going to die down there.”

— Stephen Miller, swift water rescue expert

“No one should sleep in a floodway,” says Dr. Sally Willig, a geologist who was involved in the opposition to the initial residential development on Venice Island over 20 years ago. Willig is one of the experts who testified on behalf of the Manayunk Neighborhood Council and the Friends of the Manayunk Canal in the series of zoning cases and appeals. The floodway refers to the part of the flood zone with the deepest and fastest moving water. Experts feared that residents would have to rely on swift water rescue teams to transport them to the mainland in a severe flood. Pairing this with people’s inclination to shelter in place during a disaster can have catastrophic consequences.

“Sooner or later somebody is going to die down there,” swift water rescue expert Stephen Miller said in the initial zoning case. Miller was one of several experts who also raised grave concerns about emergency management and evacuation plans for the island. Nonetheless, development proposals were ultimately allowed to move forward after a variance allowing construction in the floodway was granted by the Philadelphia Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) in 1999 with support from then-Councilmember Michael Nutter. A lawsuit from the Manayunk Neighborhood Council to contest that variance went all the way to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, which ruled against the neighborhood group. In 2008 developers submitted data to convince FEMA to reclassify the island as a flood zone rather than a floodway, facilitating construction.

Apex Manayunk, then named Venice Lofts, was one of those first two developments on Venice Island at the site of the old Namico soap factory at 4601 East Flat Rock Road. The irony of one of the most flood-prone apartment buildings in the city being named Apex is hard to ignore, and Kevin Smith, the president of the Manayunk Neighborhood Council, suspects that the name change was an effort to avoid the negative publicity associated with the old name. According to Smith, information from zoning hearings and flooding photos on the council’s website were at one point the second result that appeared in a Google search for “Venice Lofts.”

Geoff Goll, the president of Princeton Hydro, a Princeton-based engineering and design firm, imagined these scenarios when conducting hydrologic and hydraulic analyses of the island in 1999 on behalf of those opposing the development. The research predicted that floodwaters on Venice Island would rise extremely quickly, trapping residents on the island with little advance notice and potentially rendering swift water rescues unsafe in severe floods.

In Princeton Hydro’s analysis, they warned that Venice Island could be subject to currents over five miles per hour and flood waters 10 feet or higher in a severe flood, and that the river could rise to flood stage on Venice Island in the course of just a few hours, putting residents at extreme risk.

During Hurricane Floyd in September 1999, Venice Island was already underwater by the time the first official flood warning was issued by the National Weather Service.

Residential development plans on Venice Island were well underway when Floyd passed over the Philadelphia region, and the devastating flooding provided fleeting hope for Smith and the neighborhood council that those plans might be squashed or reconsidered. Instead, the recent reminder of flood risks to the island and its prospective residents were ignored just three months later when the ZBA allowed development to move forward.

Flooding on Venice Island is nothing new, with 21 severe floods reported since 1821, or about one flood every nine and a half years.

Princeton Hydro’s analysis suggests that flooding on Venice Island would be expected to recur about once every seven years. In different terms, there is about a 15% chance of a flood each year. Their report states: “In light of both Philadelphia and FEMA’s extensive regulatory efforts to protect people and property from flooding from even a 100-year flood (which has on average only a 1 percent chance of occurring each year), construction of residential developments that would face a 15 times greater risk of flooding must be considered contrary to sound floodplain management and public safety principles.”

Dranoff Properties is the development company that received the initial permit for what is now the Apex, but Smith explains that the developers generally don’t stick around for long. Their primary goal is to build and then sell the complex, and any flood precautions mentioned in the initial zoning case fall to future owners and property managers to implement.

When developers appealed the 2001 Courts of Common Pleas reversal of the ZBA ruling, they proposed several precautionary measures to mitigate impacts of housing people in a floodway, including “locat[ing] all apartment units 14 feet above the 100-year flood level, erect[ing] additions on columns constructed to resist lateral forces from flood waters, hav[ing] no first floor apartments in any building, erect[ing] a pedestrian footbridge at the second story level of the residential complex which would connect the apartment complex to the mainland and would only be used to evacuate residents in case of emergency, install[ing] an emergency alarm and speaker system, and enclos[ing] a copy of the emergency evacuation plan with each resident’s lease.”

“Our building has like half of one of those things,” said Deatrick, who recently left the building to live with his girlfriend. It’s true that there are no apartment units on the first floor of the building, which is now mostly rebuilt. However, most of the town houses at the Apex, including the one from which McLaughlin and Scott’s family had to be rescued, do include the ground floor and have no access to an emergency exit.

There is an emergency exit onto the Leverington Avenue Bridge from the second floor of the apartments that were added to the old Namico site in the early 2000s, and apartment residents used this exit to evacuate on the night of the flood. According to former resident Jake Heeneke, however, the exit was deadbolted shut and had to be cut open on the night of the flood. Heeneke had also identified another deadbolted emergency exit earlier in the day, but he says that when he asked the front desk to unlock it or cut it open in preparation for the storm, they demurred. Residents report that there is apparently no emergency alarm and speaker system, and no emergency evacuation plan included in anyone’s lease.

McLaughlin and Scott said they did not receive information on flood preparedness when they rented their town house, and they did not get flood insurance on top of their basic renters insurance, which has not reimbursed them for their losses.

A representative from JRK management did not reply to Grid’s request for information about how the property managers prepare residents for flooding.

Residents report challenges dealing with Apex management after the floods.

“After the flood happened they went through four or five different managers. When they were hired they didn’t know what was going on,” Scott says.

Moath Elhady, another Apex resident, was promised a renovated unit when he moved back in, but discovered when he arrived that they had not followed through. He persisted and was ultimately moved to the next available renovated unit, and JRK allowed him to leave soon after Ida without penalties after they mistakenly switched his lease to month-to-month.

Other residents weren’t so lucky: JRK offered to charge Heeneke $10,000 as a buyout to break his lease, even though JRK had violated their own terms on several occasions. Those still living in the Apex in the months after the flood became more and more disillusioned with the place as seemingly simple repairs to things like door locks, stairwell lights and elevators went unaddressed. Apartment tours continued, and Heeneke and Elhady began interrupting those tours to ask probing questions about whether anything about the recent and other past floods had been disclosed. JRK threatened Heeneke with legal action for one of these interruptions. One tour guide explained that they were not allowed to mention flooding on tours, and many tour guides quit after just a week or two.

Heeneke, who had encountered the locked emergency exit doors during the flood, describes a series of interactions with management in which they refused to address fire safety and code violations and took several months to address an issue with damaged carpeting in his apartment. Heeneke says that one staff member told him that the first thing she did each morning was delete any emails she’d received the day prior.

After the flood, residents scattered to nearby relatives, hotels and Airbnbs. They received no reimbursement for their temporary housing, and they reported few updates from management about next steps. They slowly returned to destruction, with ABC Action News and NBC Philadelphia reporting that one Apex town house resident, Natasha Martinez, was given five days’ notice to gather her belongings from her apartment where the floor and walls had been removed.

As many residents tried to find the easiest and cheapest way to leave, JRK slowly rebuilt. Residents report that staff members left and were replaced, the locks were eventually repaired and the gym reopened.

McLaughlin, Scott and their family settled in a house in South Philadelphia he inherited from his grandfather. “It needs a lot of work done,” he says. He also says they would like to pursue legal action against JRK, but they have not been able to find an attorney to take their case. “We are still looking for lawyers. I don’t want to let it go because I lost so much,” Scott says.

Storms capable of causing flooding are growing more frequent due to global warming. Warmer air holds more energy and moisture, which can be released via intense storms. In June 2023, the First Street Foundation released a report updating the precipitation model used to estimate how much rain will fall during storms. The currently used model is based on historic rain totals and does not consider the recent and future effects of climate change. The updated model found that what had been considered a 100-year storm is likely to take place every 29 years. In other words, a storm that previously had been estimated to have a 1% chance of happening every year actually has a 3.4% chance of happening every year. –

As other cities move away from development in floodplains, Philadelphia marches forward. New developments are planned for Venice Island at the old PaperWorks Industries mill site at 5000 East Flat Rock Road and at a site owned by Rock Urban Management at 4436–44 Main Street, a short distance south.

At a November 12, 2022 Civic Design Review meeting of the City Planning Commission, Jerry K. Roller, founding principal of Rock’s architect firm JKRP Architects, presented the plans for 4436–44 Main Street. These include a bridge to connect the second floor of the building across the Manayunk Canal to the mainland. He said that that portion of Main Street did not flood during Ida, and that City floodplain management officials agree with relying on the bridge for evacuation.

That escape route sits in what is commonly referred to as FEMA’s 500-year floodplain (in any given year it has a one out of 500 chance of flooding), and members of the commission recommended connecting the building to the Manayunk Bridge trail that passes above the site and is reliably drier. Roller said he would look into connecting to that bridge.

“[It is] definitely worth looking into just because of the 500-year floodplain issue and even the 100-year floodplain issue,” said commission member Michael Johns. “We don’t know with climate change what’s going to happen particularly on these rivers.” The commission can only offer suggestions and has no power to force developers to change their plans. As of print date, the development was still going through the design review process with the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

Josh Lippert, former floodplain manager for the City of Philadelphia, says there is little appetite for change. He explains that there are multiple factors preventing meaningful change in how the City handles development in the floodplain. Floodplain maps are outdated and, when they have been updated, it has been at the behest of developers. Proposed safety measures represent the bare minimum and are often not enforced. Most stakeholders either don’t understand or don’t care about good floodplain management.

Lippert argues that, in various projects across the city, disclosures from developers who construct these buildings to the companies that manage them through actual flood events are insufficient, as are the disclosures from building managers to renters. Kevin Smith, of the neighborhood council, refers to the planned site at 4436–44 Main Street as “more of the same,” and he mentions that while there are still several steps in the process before construction can begin, if the past is any indication of the future, it is unlikely that risky development on Venice Island will stop or that this or future buildings will be safely built or competently managed. And as climate change produces storms of increasing frequency and intensity, residents of the new building, along with those of the Apex, will face flooding again.

Grid reached out to the Philadelphia Fire Department to learn more about how past flooding at a site factors into their review of proposed construction. A fire department representative directed Grid to the City’s Department of Licenses and Inspections (L&I). A City representative replied that the permits required for building in a floodplain do involve extra requirements on top of what is usually required for building outside of a floodplain: “The requirements are largely derived from federal FEMA regulations.” L&I inspects buildings during construction, but later code violations (such as the locked exits encountered by Heeneke) should be reported to Philly311 so that L&I can respond with an inspection. As for existing buildings like the Apex, “the City does not have a process in place that requires permanent evacuation of existing, occupied properties due to propensity to flood.”

With L&I not equipped to react, the onus for protecting residents in flood-prone areas (present or future) largely falls on elected officials. They have repeatedly failed in this task. In 1999 Councilmember Nutter pushed through the rezoning that permitted construction of the Venice Lofts. In 2018 the City Planning Commission voted to reject building additional town houses on another parcel of land on the island because they would put residents’ lives at risk during a flood. As an advisory body, however, they had no power to back up their recommendation. In spite of the experts’ safety concerns, City Council unanimously voted to change zoning to permit their construction.

Curtis Jones, the councilmember whose district includes the island, did not respond to Grid’s requests for comment.

These same flooding issues happened at every “luxury” apartment complex built alongside the Schuylkill banks in the past 20 years. I have no ideas how any of these buildings were approved by local governments. What good is a home that gets destroyed every decade? Pure greed!

Adam,

Congratulations for researching and writing your thoughtful, fair and thorough article above.

The Eastwick development, years ago right in the flood plain, should have been the “forever lesson” locally not to build in a flood prone areas. People never learn, do we!

The decades long bicker we all followed about Venice Island should have been decided by wiser people, but money talked, politicians balked and the lovely public park on the Schuylkill River there, that should have been, was lost!

With 330 million people now, more than twice the 140 million in the early 1950’s, more and more people will live in forest fire prone, flood, earthquake, hurricane and all disaster prone lands. Maybe fewer people ought to be our long term goal for a better USA?

Developers have no moral code and people pay little attention to nature. We cannot depend on millionaires and billionaires to be concerned with anything but more money in their greedy pockets. Listen to history, future climate crisis predictions, and the neighbors. The city is negligent in so many ways and nature rules.

At my request, Mr. Lippert agreed to speak to the residents of my development. Despite my multiple entreaties, the HOA declined to accept his assistance.

Maybe everyone should move out?