At Houston Meadow it’s easy to forget the city. Grasses and wildflowers cover the hillside that slopes into the wooded ravine of the Wissahickon Creek below. Bees and butterflies dance across the flowers. Over at Three Springs Hollow in Pennypack Park hikers can walk beneath towering oak and tulip trees while wood thrushes serenade them. It all might look natural and wild, but in the forests, meadows and waterways of the Fairmount Park system, nature needs a hand. Philadelphia Parks & Recreation’s Natural Lands team works to restore and maintain habitats like these for human visitors and wild residents.

Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park system was assembled by the City from the mid–1800s to the early 1900s. Workers mowed lawns and tended shade trees, but up until the end of the 20th century, the forests, meadows, marshes and streams were more or less on their own. Trees sprouted and raced for the sky across thousands of acres. In other areas, what had been meadows maintained by grazing livestock gradually shrank as the forest encroached on their borders.

By the end of the 1900s much of the unmanicured land of the Fairmount Park system wasn’t in great shape. Deer proliferated in green spaces where no one hunted them. They devoured new trees and shrubs before they could find their place in the forest. Exotic plants that deer don’t like to eat, such as Amur honeysuckle, Japanese knotweed and garlic mustard, filled the empty spaces.

Help arrived with a $26 million grant to the City from the William Penn Foundation, celebrating its 50th anniversary in 1995. The money was intended to fund ecological restoration, expanded environmental education programming and volunteer stewardship capacity. Thus was born the Natural Lands Restoration and Environmental Education Program (NLREEP).

If we want to have wild woods, we are going to have to maintain it.”

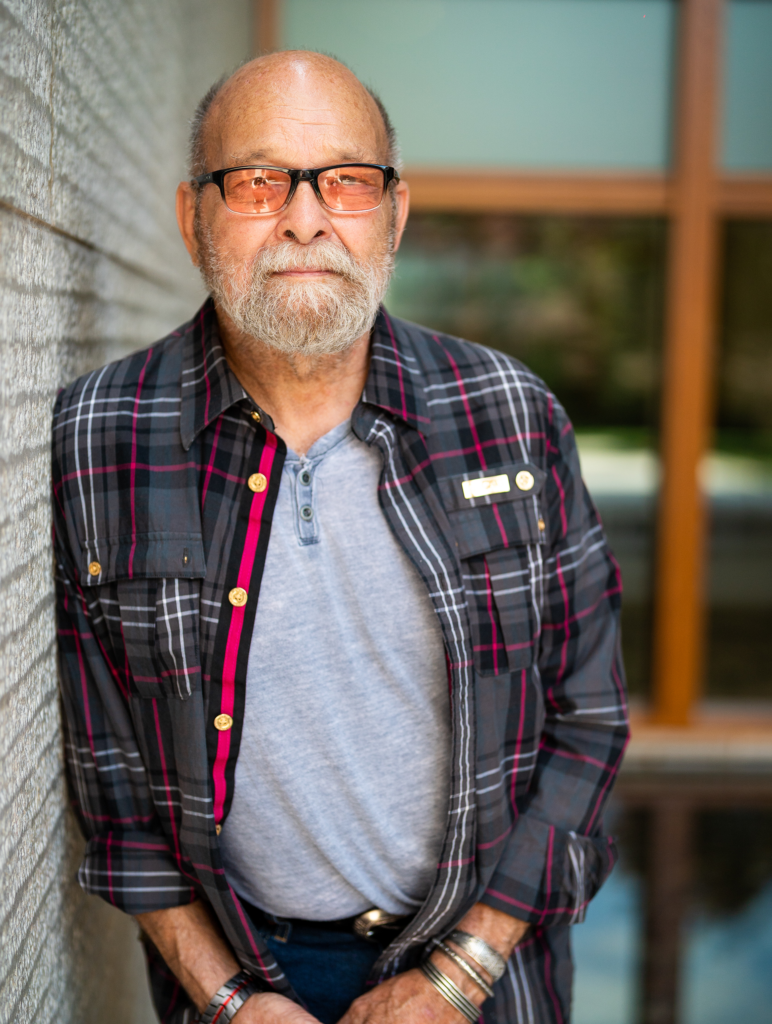

– Tom Dougherty, Philadelphia Parks & Recreation ecological restoration, retired

“What people would often say to me is, ‘Doesn’t the woods take care of itself?’” says Tom Dougherty, who worked for NLREEP in volunteer stewardship and then ecological restoration before retiring in 2020. “The answer is it may have at a different time, but now in the 21st century urban forest is kind of a contradiction in terms. If we want to have wild woods, we are going to have to maintain it.”

“The purpose of the $26 million to the park was to develop a plan to restore natural areas,” says Nancy Goldenberg, the first director of the program and currently president and CEO of Laurel Hill cemetery. Goldenberg says that when she came on board “there was nothing. We didn’t have an office. ‘Here is $26 million. Figure it out.’ I had to hire staff, do an organizational chart and put a budget together.”

Before they could figure out what to restore, the new unit had to figure out what was growing and living in the parks in the first place. “We hired the Academy of Natural Sciences to do the inventory,” Goldenberg says. “You have to know what’s there before you can restore it. It was a dream team, and the data we got was extraordinary.”

NLREEP initiated pilot projects as well, realizing that they couldn’t wait until the inventory, which took four years instead of the one year that had been planned, was complete to start restoring habitat. “The first thing we did was a hillside in the Wissahickon that was at the Walnut Lane Golf Course, where it comes down to Forbidden Drive,” Goldenberg says. “The sign is still there. [With] everything we did, we wanted to educate people on what we did and why. We tried to marry education and civic engagement with the actual work.”

The program initially planned to expand existing nature centers and add new ones in FDR Park and in Fairmount Park East in the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood. “The only one that got done was the expansion of the Pennypack Environmental Center,” Goldenberg says.

It was clear that the scale of the work dwarfed the resources. “$26 million gets you a lot of leverage, but nowhere near enough,” says Dougherty.

Over the years the restoration strategy evolved to reflect real-world limitations. Joan Blaustein, the park system’s former director of urban forestry and ecosystem management, started in 2006. “From when I was there until 2010 we continued working from the master plan that had been done by William Penn Foundation funding. Then in 2010 we got a little bit of funding to redo the … forest management plan,” Blaustein says. “We took a hard look at what our capabilities were and what our challenges were, which were enormous. We determined we couldn’t restore areas and walk away from them, due to deer and invasive species. That was an exercise in futility. We decided we would change our approach, that we would do large-scale restorations only if we could install a deer fence. Otherwise we weren’t going to do it.” Parks & Recreation’s urban forestry initiative launched in 2013, and new projects under the initiative kicked off in 2015.

The philosophy of restoration changed as well, moving away from thinking historically and trying to recreate the past. “That became impossible because you could never recreate it, not with the pressure of insects, deer and climate change,” Blaustein says. “We had to think of what the new structure of forests would be and how we could manage and preserve what we could.”

The organizational landscape was shifting as well. In 2010 the Fairmount Park system merged with the City’s Recreation Department, creating the current Parks & Recreation Department. The environmental education and volunteer stewardship functions of NLREEP were split off under the new bureaucracy, leaving six full-time staff working on natural lands restoration.

The reduced unit has further atrophied in recent years, with positions such as the operations manager going unfilled after retirements. According to the City’s 2023 Tree Plan, “currently, there are only three full-time Philadelphia Parks & Recreation staff members and two full-time Fairmount Park Conservancy staff members in the Natural Lands team responsible for managing and protecting 5,600 acres of forest, meadows, and streams.”

The unit could be poised for a turnaround. Cherelle Parker, the Democratic candidate for mayor, has called for doubling Parks & Recreation’s operations budget.

The Tree Plan calls for eight additional staff positions to tend the urban wilds, recognizing their importance in the health of the city. (Grid reached out to Parks & Recreation for an update on natural lands staffing but had not heard back as of press time.)

“That’s where the work happens. The work of natural resources happens in the forest,” Blaustein says. “Air is cleaned, water is cleaned. It doesn’t happen in mowed lawn. We need big mature trees, deep roots and soil.”

“They’re sort of the lungs of the city, and they are very important around climate change,” says Michael DiBerardinis, who headed the William Penn Foundation from 2000 to 2002 and with the City oversaw the park system merger in 2010. “They clean the air and provide temperature relief during the increasingly hot summers we’re having. They provide tens of thousands of people with recreational activities adjacent to their neighborhood[s] … They really provide a place for people to enjoy nature beyond their important environmental features.”

Natural Results

Are you a Philly parks fan? Here are five projects for which you can thank the Natural Lands team

1. Three Springs Hollow

The forest canopy soars above Three Springs Hollow on the north side of Pennypack Creek, between Krewstown Road and Bustleton Avenue, but by the early 2010s the forest managers realized that new trees weren’t growing up to replace their elders. After erecting a fence to keep deer (like this young buck found outside) from eating seedlings didn’t do the trick, the unit initiated tree plantings to see what would work to kickstart forest regeneration. The forest in the hollow “was really, really nice to begin with, so we fenced it in, and have since been planting,” says Tom Dougherty, formerly of Parks & Rec. The plantings include hybrid American chestnut trees, a species that once formed a major portion of the region’s hardwood forests but that was wiped out by chestnut blight in the early 1900s.

2. Houston Meadow

Next to the Andorra neighborhood of Northwest Philadelphia 30 acres of meadow spread across the hillsides at the edge of the Wissahickon Valley. After hundreds of years as open agricultural fields and pastures, the land had grown in with trees as part of the park system. Keith Russell, program manager for urban conservation with Audubon Mid-Atlantic, had birded in the meadows in his youth and had watched as they dwindled and grasslands bird species disappeared. In 2007 Russell and the Natural Lands team’s Tom Witmer hatched a plan to restore the meadow, and with funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and other sources they were able to cut the trees back around the edges and re-seed the meadow with native grasses and wildflowers.

3. Haddington Woods

In Haddington Woods, a section of Cobbs Creek Park north of Market Street in West Philadelphia, a deer-proof fence protects what could be the future of urban forestry in Philadelphia. As global warming cranks up the temperature in city forests, some snow-loving species of trees, such as sugar maples, will likely disappear. Their replacements might currently grow to the south, where forests have evolved with the climate that awaits Philadelphia. To get ready, City foresters have planted southern species such as loblolly pines in Haddington Woods.

4. Greenland Nursery

The Greenland Nursery in Fairmount Park West dates back to the late 1800s but launched in its current form in 2009. The nursery staff harvests seeds and cuttings from native plants growing in the park system and uses them to generate more plants for ecological restoration work. “We were not seeing a lot of natural regeneration in the forest, so we’ve had to get involved,” says Max Blaustein, the nursery’s director, quoted in Grid #122 (July 2019).

5. FDR Park South Meadow Lake

Meadow Lake in FDR Park is a great spot for watching winter waterfowl, but up until the early 2000s, the southern portion of Meadow Lake was “a broken-down concrete swimming pool,” says Dougherty. That pool had been built on top of what had originally been part of the lake. “The freshwater lake had been reshaped, filled and armored to facilitate its conversion to a swimming pool,” according to a project summary by Biohabitats, the engineering firm hired to restore it. With the pool in disrepair, NLREEP used a grant from the state’s Growing Greener program to pay for Biohabitats to rip out the concrete (which was used to elevate chronically soggy baseball fields nearby), restore the lake with native vegetation and install a walkway with signage, allowing park visitors to access the site.