On a Sunday afternoon in early June, Jorge Oliveras and Jackie Colon packed up their beach chairs, filled a cooler with snacks and brought their children out to Devil’s Pool. They sat amid a loose constellation of rocks at the confluence of Wissahickon and Cresheim creeks, watching their kids swim and splash around, basking in the sun, water and forest that surrounded them.

The warm weather had brought nearly 100 visitors to the site that afternoon to dip and dive into Philadelphia’s most notorious swimming hole and its neighboring waters. Some had started small fires on the creeks’ banks or in portable grills balanced among the rocks to cook a meal fit for the scenery. Teenagers and twenty-somethings leapt off 15-foot-high cliffs into Devil’s Pool, the sound of their screams colliding with the music bouncing around the valley walls that have made this location a gathering place for centuries. Nearby, a man encouraged his dog to swim.

The crowds that flock to Devil’s Pool each summer are a testament to its unique status in the region as an outdoors destination that offers something no public pool ever could.

“There’s a connection with nature,” Oliveras said. “If you’re going to a swimming pool, you don’t feel that connection — that you’re close to the trees and the water and the fishes, being out in the sun and having fun.”

That connection has made visiting Devil’s Pool a generational affair. Like many who spend time there, Oliveras first came with his family when he was young. But the natural and elemental beauty that brings crowds to Devil’s Pool exists in contrast to Philadelphia’s prohibition against swimming in the city’s waterways, in part to protect nature and in part to protect visitors. Just 48 hours earlier, a man had drowned in a different section of Wissahickon Creek. Two weeks later, another drowned in Devil’s Pool itself.

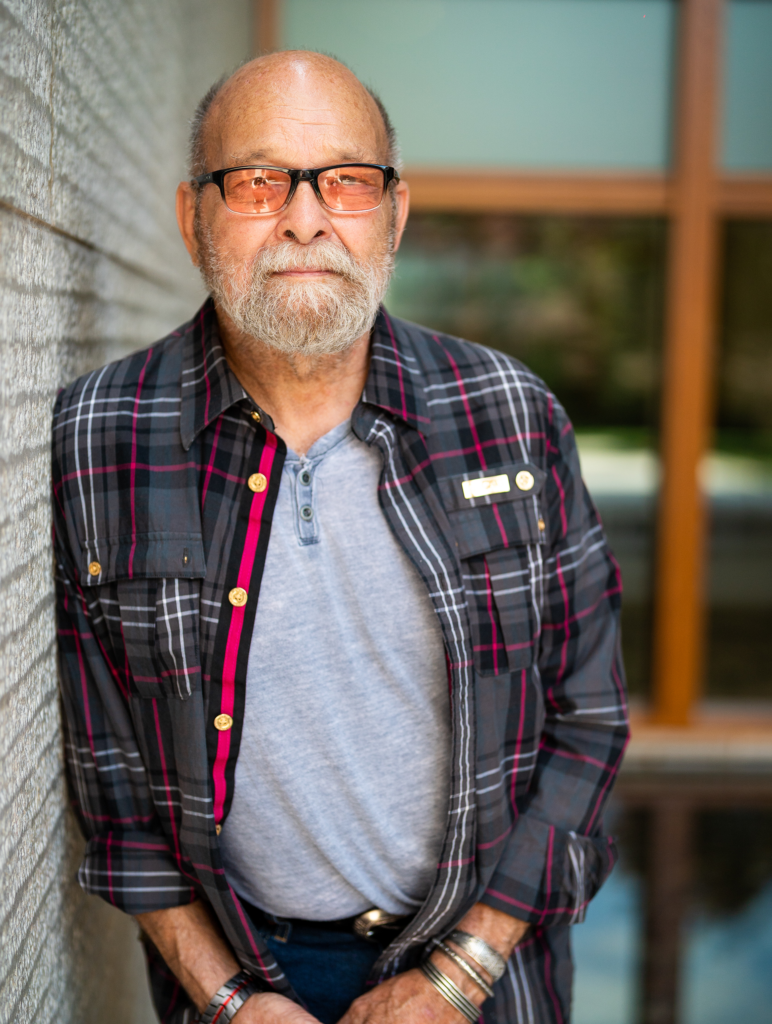

Craig Johnson, who for 11 years has lived in Glen Fern, the 300-year-old stone house at the bottom of Livezey Lane, just a few hundred feet from Devil’s Pool, said a half-dozen accidents at the site each year require emergency attention from first responders. In addition to the risk of injury and drowning, the water can also become polluted after rainfall because of the city’s use of combined sewer overflows. Despite these concerns, Devil’s Pool has remained a special setting for generations of Philadelphians.

“The biophilic benefits of connecting with nature, connecting with natural water and being in that kind of environment in a safe social landscape are enormous,” Johnson said. “I can’t tell you how many happy people and happy families we see coming and going, having one of the best days of the year to get out and be in this kind of an environment that is quite unsupervised.”

The freedom afforded by Devil’s Pool is a significant part of its appeal to Nathan, 16, one of Oliveras and Colon’s children who was enjoying their family outing that Sunday. He appreciates walking over the rocks that have surrounded Devil’s Pool for hundreds of years and seeing fish swim past when he’s in the water.

“When you’re here, nobody can rule you,” he said. “You can be yourself. But with that you’ve got to be careful of certain things. This isn’t a pool, and there’s no lifeguard.”

Among other typical poolside amenities, the location also lacks restrooms and trash cans — an understandable if unfortunate reality for a natural setting that isn’t intended by the City and its park system as the summer hangout it has become.

[W]e are not an enforcement group, so we really are working to engage visitors, educate and hope to spark something in people to at the very least carry out what you carried in.”

– Ruffian Tittmann, Friends of the Wissahickon Executive Director

Ruffian Tittmann, executive director of Friends of the Wissahickon, said her organization has gone “all-in” on its leave-no-trace approach to the park, working to educate visitors about the harm caused by any trash, waste or food they leave behind. The Friends clean up tons of trash from the park each year, including at Devil’s Pool, but “we are not an enforcement group, so we really are working to engage visitors, educate and hope to spark something in people to at the very least carry out what you carried in,” she said.

Having witnessed all aspects of what Devil’s Pool offers and invites over the years, Johnson said he wishes the area had improved signage to give visitors the information they need to enjoy themselves responsibly — both for their own sake and for the park’s.

“I would do more to help visitors understand the cultural and natural history of the site, not just for education purposes, but because they’ll care for it more,” Johnson said.

The City prohibits not just swimming but also wading and sitting in creeks, and “visitors of all ages consider this policy to be unjust, unenforceable and ridiculous,” Johnson said. If the prohibition exists to protect people from the water itself, water quality sensors could be installed to create dynamic indicators that would inform visitors of what to expect when they wade in, he suggested. And if the prohibition is intended to protect the landscape, even the simple presence of trash cans would help.

To Nathan Boon, a senior program officer with the William Penn Foundation, whose aims include improving water quality and recreational access in the Philadelphia region, “traditional parks infrastructure” would go a long way toward improving the Devil’s Pool experience by creating harmony between recreation, safety and preservation. He wants to help the region’s waterways shed their reputation for being unclean so more people can engage with nature.

“There’s a spiritual connection there for folks in the ability to immerse yourself in a natural water body,” Boon said.

Boon has watched as visitors have traveled to the Wissahickon in record numbers in recent years, particularly as Philadelphians sought refuge and relief in nature during the pandemic. Like Oliveras and his family, Boon appreciates the powerful presence of Devil’s Pool as a shining asset in the city’s park system. Its ability to attract so many visitors despite its risks and imperfections — and the City’s desire to keep people out of the water — makes it a site that should be celebrated and supported in all it has to offer.

“You’ve got a phenomenon that is worth accommodating,” Boon said.

Grid reminds readers that, however popular and compelling, swimming at Devil’s Pool remains both against park rules and dangerous.