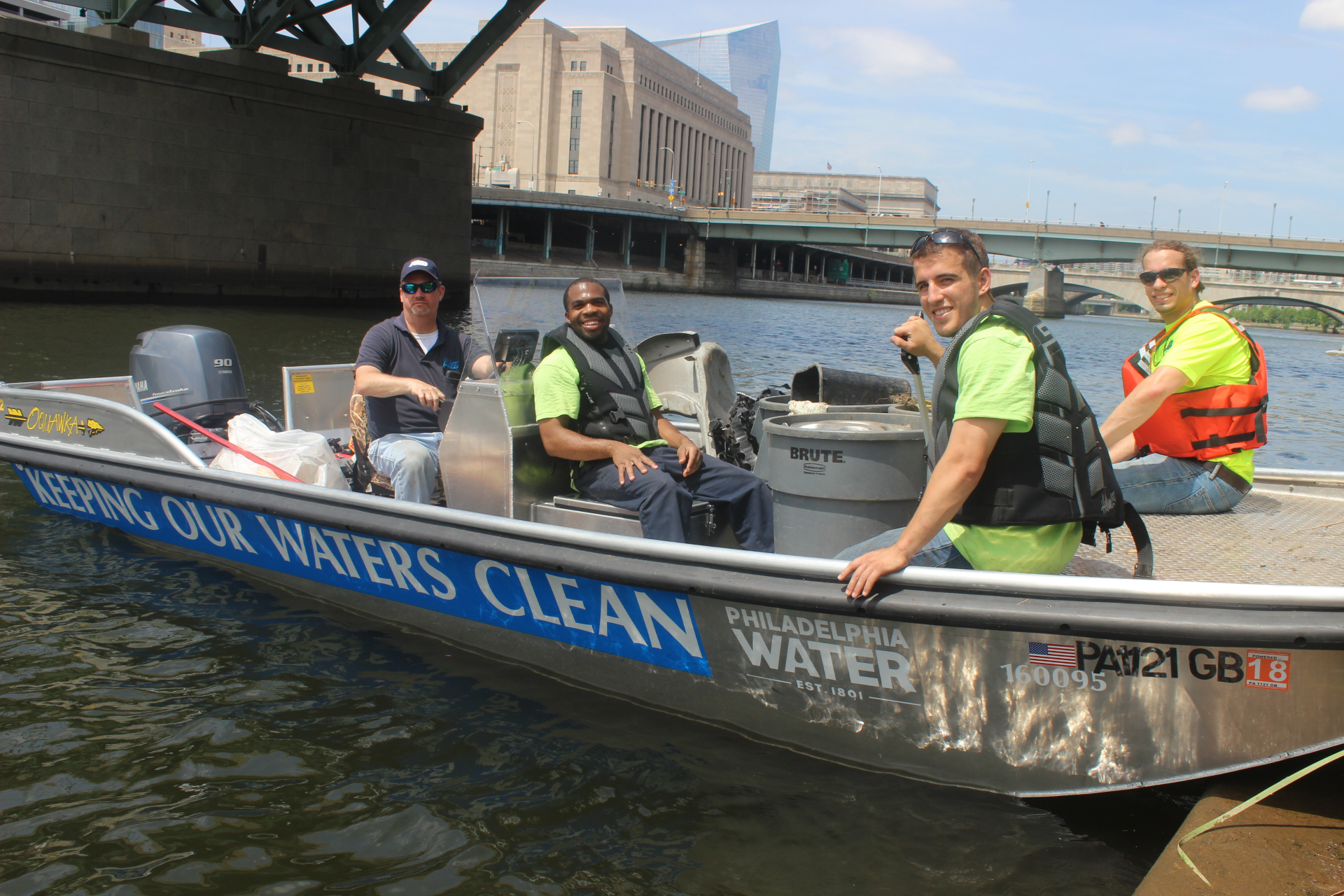

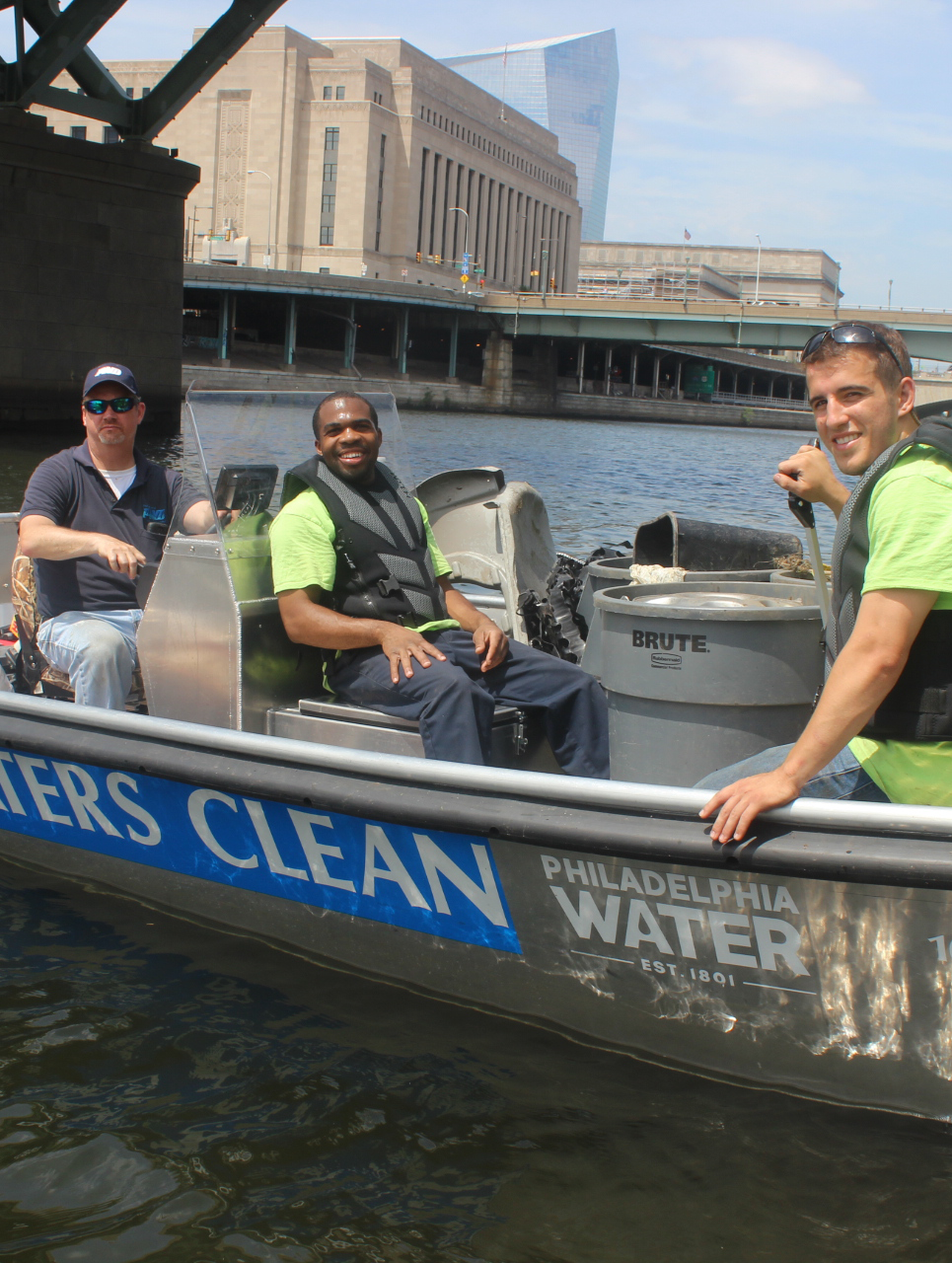

Three Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) trash skimming boats ply the waters of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, floating goalkeepers trying to prevent plastic debris from reaching the ocean.

The current circulating around the North Atlantic leaves a quiet section of ocean in the middle called a gyre. A patch of plastic garbage hundreds of miles across floats in the North Atlantic Gyre, and more than a few plastic bottles from the streets of Philadelphia rise and fall with the waves. Gradually they break down into smaller pieces under the force of waves and solar radiation. The plastic bits then sink lower in the water column, eventually landing in the stomachs of sea creatures or the sediments at the bottom.

Until a ban on single-use containers is enacted, there will be nothing new about the best ways to keep Philly plastic out of the ocean: reduce, reuse, recycle. This summer the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University sponsored 10 works of art to encourage Philadelphians to consume less plastic by using reusable water bottles instead of buying bottled water. Silas McDonough’s Waterline exhibit, viewable at the academy through January 8, portrays three large plastic jugs, themselves made out of recycled plastic.

Sadly, bottled water and other single-use plastics are still available for sale in Philadelphia. And some of that single-use plastic lands on the sidewalks and streets, where it is eventually washed into the curb-level openings of storm sewers. There the plastic enters the domain of PWD.

Every day, PWD crews clean grit, leaves, sticks and trash out of the storm sewer inlets. So far in 2022 they have pulled about 5,000 tons of debris, all of which can clog inlets, forcing stormwater into the streets and exacerbating neighborhood flooding. This makes removing the debris a disaster preparedness measure, but it also keeps the plastics from escaping into our waterways.

It’s hard work, but rewarding to get litter and trash from those hard-to-reach areas.”

— Brian Rademaekers, Water Department spokesperson

For the bottles (and half-deflated basketballs, baby doll heads and other floating plastic) that make it into the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, PWD’s trash-skimming boats take over the effort, removing 10 to 20 tons per year.

Plastic washing into Philly waterways is a big problem, says Maria Horowitz, an environmental engineer with PWD. “Unfortunately we could always do a better job of dealing with it. Skimming boats are the last line of defense.”

PWD depends upon a 20-foot boat, a 25-foot landing craft with a drawbridge that facilitates loading debris and unloading equipment and the 38-foot R. E. Roy trash skimmer.

The R. E. Roy, operated by a contractor, “has a suction functionality and a clam shell. It can go and grab things,” says Horowitz. As a larger boat, it sticks to the center channels of the Delaware and the Schuylkill.

The smaller boats bring cleanup efforts closer to the banks. “You can get into places like the dam at the Art Museum, picking up trash you might not be able to reach otherwise,” says Brian Rademaekers, a PWD spokesperson. “It’s hard work, but rewarding to get litter and trash from those hard-to-reach areas.”

For more than 20 years PWD senior scientist Lance Butler has captained department vessels for trash cleanup efforts as well as for research, infrastructure inspection and public outreach. Although Philadelphians still use a lot of single-use plastic, Butler believes that less of it has been making it into the rivers.

“One of the misconceptions [of Philly river water] is that it’s filthy. Yes there are debris and floatables, but compared to 20 to 25 years ago the rivers are much cleaner. It was hard to navigate in the late ’90s or 2000s on a good day,” Butler says. Back then he often ran into logs, plastic barrels or “marine debris” such as floating chunks of marinas. “I have recollections of … large trash islands coming down the Delaware River or in some instances in the tidal Schuylkill, but I do not see that anymore.”

Even as the overall volume of trash in the rivers has decreased, one thing has remained the same. Most of that volume is plastic, Butler says. “It’s something that not just the City of Philadelphia but the nation as a whole has to get a handle on.”