In a city with a long history of woeful recycling rates, Dyvert is trying to make a difference.

The Philadelphia-based company aims to boost the circular economy by improving the messaging found around waste, recycling and compost bins to make them more effective and efficient. Its products offer public facilities the ability to display commonly used items in an enclosed transparent lid that sits atop waste bins to clearly instruct people where to put their trash and recycling.

At a stadium, for example, water and beer bottles would be displayed around the opening to a recycling bin, while hot dogs, pretzels and paper waste would be shown in the lid to a trash can. By clearly demonstrating what goes where in a site-specific context, Dyvert’s products eliminate the guesswork that often flummoxes people — and the contamination that makes recycling less efficient.

For founder Ben Ditzler, this simple but effective messaging is an important tool to improve the way Philadelphia and the rest of the world recycles.

“It comes down to what I’ve always felt about recycling and waste,” Ditzler says. “It’s really the front door to sustainability.”

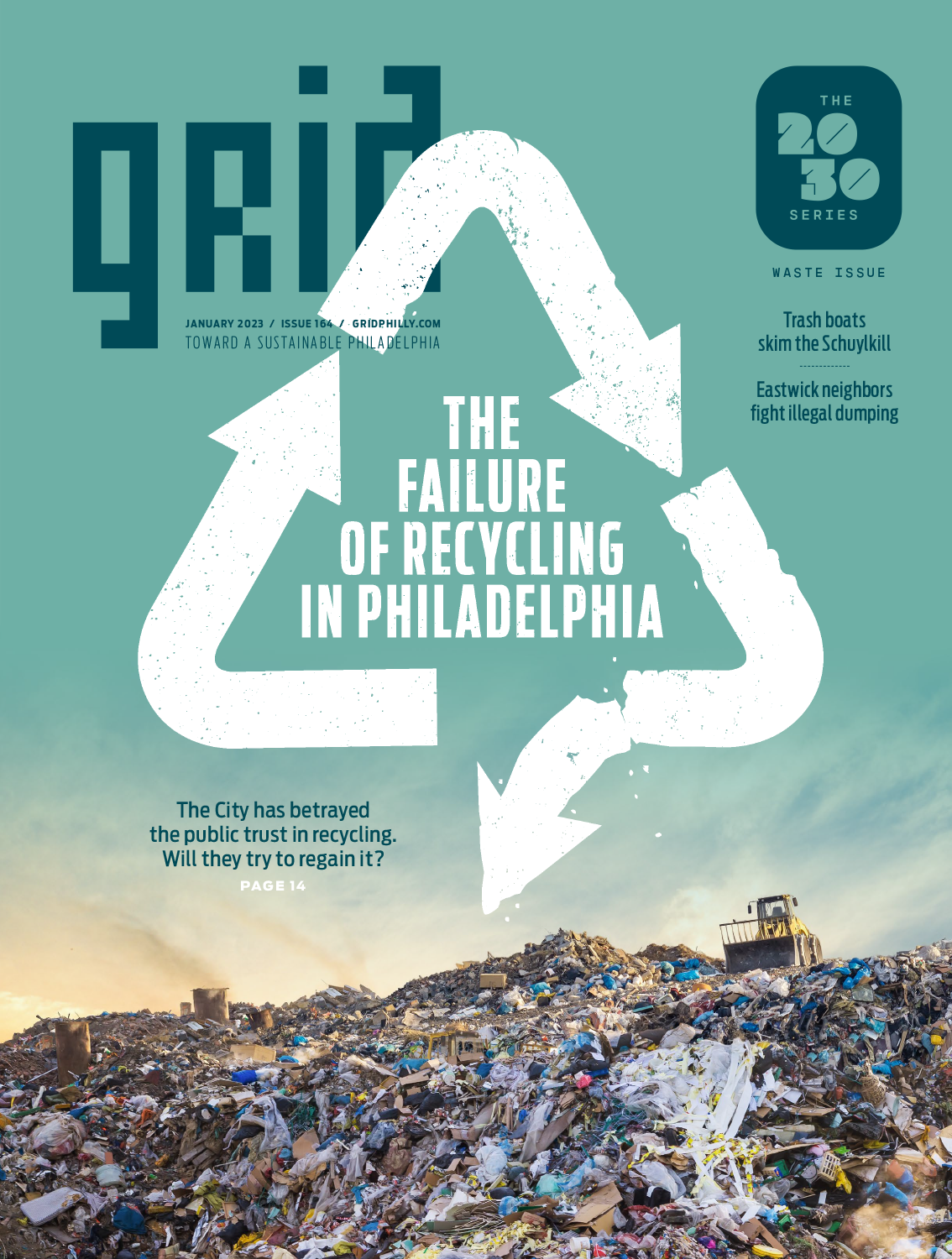

With that in mind, the former civil engineer is hoping Dyvert can be a stepping stone toward broader improvements in Philadelphia’s approach to environmentalism. The city’s recycling rate has dwindled into the single digits since the pandemic and was already significantly behind many major cities before then. Confusion about what to recycle is part of the problem.

In a two-week study at the University of Pennsylvania, Ditzler says, results showed that contamination was nearly cut in half and recycling diversion rates increased significantly when using Dyvert lids, compared with the normal text-and-image messaging that was previously used near waste bins. By cleaning up recycling from the consumer side, Ditzler wants to help fix underwhelming rates and expand sustainable thinking at the same time.

“As people grasp that there’s a small step they can take, they start thinking about bigger steps they can take individually but also collectively as a society,” Ditzler says.

Ditzler’s interest in recycling goes back a long way. He grew up visiting the recycling center in his hometown of Ridgefield, Connecticut, and he helped his neighbors acquire recycling bins after he bought a house in Philadelphia in 2006 and realized that he was the only one on his block recycling. After getting into the sustainability community around that same time, he worked as a recycling consultant and on waste composition studies.

“I actually liked digging through the trash,” he says. “Who would’ve guessed?”

In 2014, he was working on a commercial recycling toolkit for the city when the idea for an improved messaging system struck him while riding the El. He acquired the patents for Dyvert, launched in 2019, and is now beginning to roll the product out to Philadelphia locations, including architecture firm KieranTimberlake and education nonprofit Mighty Writers. Xavier University of Louisiana is about to put 60 of Dyvert’s units on its campus, picking up on Ditzler’s pitch to simplify the work of facility managers.

“Everyone generally understands that recycling is good, but they get a little iffy when it comes to what to recycle,” says Angeliqué Israel, literacy leader in Mighty Writers’ West Philadelphia location, who has used the Dyvert unit to teach the children in her afterschool program about recycling. Thinking more deeply about landfills and recycling centers has led her to find a recyclable option for the single-use cups children use every day across Mighty Writers’ 10 locations.

Dyvert can’t solve all of Philadelphia’s recycling or sustainability problems, but Ditzler wants it to be part of the solution.

“It can be difficult and daunting to think of the big picture,” Ditzler says. “If you can at least start thinking small, start thinking bottles and cans — and we know that’s just the tip of the iceberg — it really opens your eyes to what else is out there.”

Nice article!