The sound of trees being cut down woke Fred H. Cartwright on the morning of February 23.

“Saw, crackle, then boom. Then a minute later, saw, crackle, boom. It had us all out of the house looking to see, ‘What is that noise?’” recalls Cartwright.

Cartwright lives on Wyndale Avenue, a well-kept one-block street of two-story brick row houses in the Overbrook Park North neighborhood of West Philadelphia. The block of Wyndale runs northeast to southwest and then makes a 90-degree turn at the edge of Cobbs Creek Park to become 77th Street.

Up until that morning, the end of the block looked out on about 30 acres of woods at the northern edge of the Cobbs Creek Golf Course. The columnar trunks of tulip trees, red oak and other hardwood trees climbed to a canopy more than 100 feet above. Judging by the rings on trees that have been cut down, these woods were there for about 100 years.

India DiValerio lives on the end of Wyndale by the woods, and the noise woke her up as well. “When I heard all the clunking … I didn’t know what was going on. Seven o’clock in the morning, boom, boom, boom. You couldn’t sleep. It was nonstop all day.”

Seventeen years ago, Cartwright and his wife were looking for a larger house, but Wyndale caught their attention. “It’s eye-catching when you drive on the block,” he says. “We said, ‘Man, it is small,’ [but] we looked out and saw this beautiful woodland. We said, ‘Man, it’s nice.’”

DiValerio has lived on the block for 25 years. “The reason I moved onto this block was because it was a quiet tree-lined street, a one way,” she says. “That land over there was one of the reasons.”

Neither Cartwright nor DiValerio knew about the tree cutting ahead of time.

Development for whom?

Project advocates have touted that the Cobbs Creek Golf Course, which opened in 1916, stood out in its early history as having been an integrated, women-friendly course during segregation, when most private clubs and the PGA were open to white men only.

Today, the residents of the West Philadelphia neighborhoods around the Cobbs Creek and Karakung golf courses don’t resemble the golfing public.

The population of the 19151 zip code, which includes Wyndale, is 89% Black. It has a median household income of just under $50,000 and a per capita income of $25,000, according to 2019 U.S. Census statistics 20.3% percent of residents live below the poverty line, and 55% are female.

By contrast, 80% of golfers are white and 77% are men, according to a recent article in Ebony Magazine about efforts to diversify the sport. Benchcraft, a company that sells advertising on golf supplies, signs and benches, claims that the average golfer’s household income is more than $100,000.

Golf is also an expensive sport. The cheapest set of clubs at Dick’s Sporting Goods is about $300 (on sale), and a single round of 18 holes at the Cobbs Creek Golf Course will set a Philadelphian back $68 on a weekday and $78 on a weekend, according to an exhibit in the lease that the Cobbs Creek Foundation signed with the city. The nine-hole Karakung course will cost Philadelphians $30 on weekdays and $35 on weekends.

“I don’t golf. I don’t know anyone that golfs,” DiValerio says.

Cartwright says he once tried hitting balls on a driving range but hasn’t golfed since.

How it began

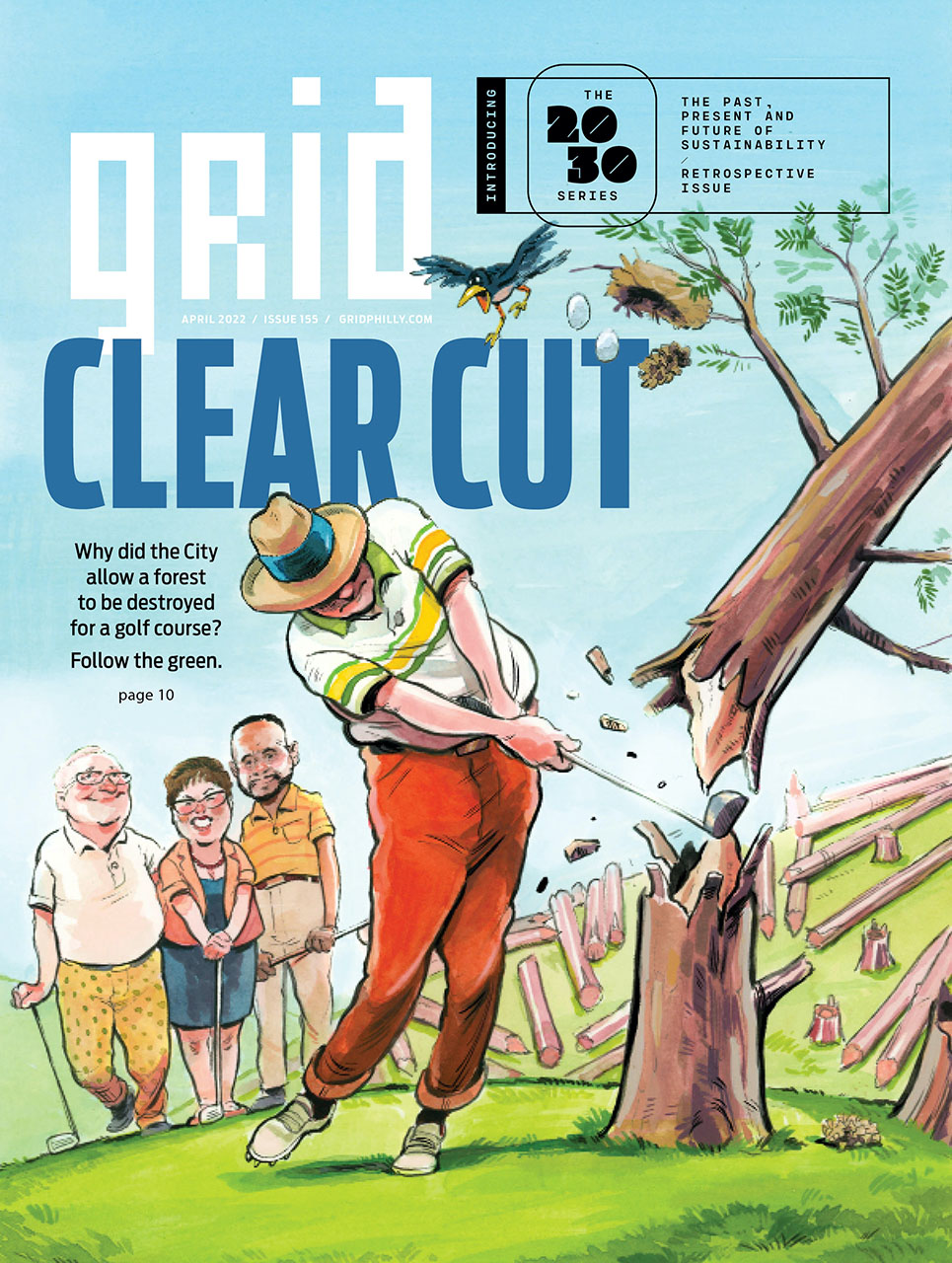

Not surprisingly, the idea to overhaul the golf courses, and cut down more than 100 acres of trees in the process, did not arise from the demands of the golf courses’ neighbors, or, for that matter, from anyone in West Philadelphia.

It began in 2007 with a group of golf course design enthusiasts who met on an online forum called Golf Club Atlas. Led by Mike Cirba, a technology officer from the Lehigh Valley, they dug into the history of Cobbs Creek and Karakung golf courses and realized that the Cobbs Creek course, in particular, had once been one of the gems of the golfing world. A Cold War redesign to accommodate anti-aircraft missile launchers, decades of deferred maintenance, as well as chronic flooding from the creek, had left both courses in rough shape.

They launched a blog, printed a spiral-bound book with historical photos of the course and formed a group called Friends of Cobbs Creek Golf Course. With some encouragement from the Fairmount Park Commission (a predecessor to Parks & Recreation), they began planning and fundraising.

In a pair of YouTube videos from 2013, Cirba and Joseph Bausch, a chemistry professor at Villanova University, talk about their vision for the course while referring to paper plans for the renovation. (The maps in their hands look virtually identical to those currently being shared by the foundation, nearly nine years later.) They speak about their desire to involve the community and to keep the golf course affordable. In one video Cirba says: “Some trees will be removed, some trees will be planted in other areas,” but that they intend the project to have a net environmental benefit.

A group of golf course design buffs weren’t able to carry out a multi-million-dollar golf course renovation on their own. That took golf enthusiasts with a lot more money, and much better connections.

Chris Lange, a commercial real estate broker and competitive amateur golfer got involved in 2010, and by 2016 they had lined up support from the family of insurance magnate James Maguire Sr. In 2018 the Philadelphia City Council passed legislation authorizing Parks & Recreation (PPR) to enter into negotiations to lease the golf course, and the Cobbs Creek Restoration and Community Foundation (aka the Cobbs Creek Foundation, or CCF) was formed. On December 28, 2021, the foundation signed a 30-year lease, paying $1 to rent 350 acres of city property assessed at over $92 million.

Since 2017, Curtis Jones’ campaign has received at least $22,000 from individuals or organizations connected with the Cobbs Creek Foundation.

A family affair

Who are the people from the Cobbs Creek Foundation? A James Maguire is listed as a director, and the chairman is Chris Maguire, who also serves as a director of the Maguire Foundation, a major funder of the Cobbs Creek Foundation. Megan Maguire Nicolleti, also listed as a director, is the President and CEO of the Maguire Foundation, and a fourth Maguire, Lucy, serves as the vice president of development.

Looking beyond the Maguires, Chris Lange is the founding CEO, and Chris Lange Jr. is vice president. A director named Amara Briggs is a banking executive from Bala Cynwyd. Charlie Pizzi, chair of the Independence Health Group (owner of Independence Blue Cross), and Carl Jones Jr., a Comcast executive, are also directors.

Philadelphians might recognize other directors such as Harold T. Epps, the city’s former director of commerce, and U.S. Circuit Court Judge Marjorie Rendell, ex-wife of former Philadelphia mayor and Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell.

The people behind the foundation are wealthy and well connected.

In 2017 Councilmember Curtis Jones Jr., whose fourth district includes the courses and the surrounding Philadelphia neighborhoods, introduced the legislation to allow the city to negotiate the lease. Since then, his campaign has received at least $22,000 from individuals or organizations connected with the Cobbs Creek Foundation.

In an eight-day period in September 2021, several individuals connected with the foundation, as well as the foundation itself, made donations totaling $7,000.

The foundation’s donation of $2,500 is illegal due to its status as a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, which are barred from taking part in political campaigns.

After Grid revealed the donation on March 2, foundation communications representative Michael Rodriguez told Grid the donation was an “error” and they are working with Jones’ campaign to have it returned. These donations occurred while the foundation had zoning permit applications pending for clearing trees on the golf course and was still negotiating the lease.

At the end of December 2021 the lease was signed, and two permits for clearing trees on most of the site were approved. Two other permits for clearing on steep slopes were denied, though the foundation appealed. As of March 13, the appeals have been withdrawn.

DiValerio had not been aware that Jones had received campaign contributions from he foundation as well as individuals connected with it until asked for her comment.

“The next time he goes to run, I’m going to make it my business to make sure he doesn’t win,” DiValerio says. “You work for the people who got you in office, not the people who put money in your pockets.”

An engaged community?

Grid asked the foundation for details about its community outreach process. Rodriguez’s emailed response neglected to provide information about what groups they met with, when or where: “Since 2019, CCF has held multiple meetings with civic leaders, religious leaders, residents, community organizations and others … In total, CCF met with more than 100 community members.”

More than 33,000 people live in zip code 19151.

Clearly, the community outreach process began well after Cirba and the other organizers had decided on the design for the course (which was no later than 2013), and a year after the city passed the legislation authorizing PPR to begin negotiating the lease in 2018.

Unsubstantiated claims

When Grid questioned PPR and the foundation about why so much deforestation was necessary, they said that the existing trees were actually a problem.

“The rampant spread of invasive species and overgrowth along with creek deterioration and heavy flooding create an unstable environment for any natural landscape to thrive,” according to Maita Soukup, communications director for PPR.

“We do not take the removal of trees or vegetation lightly,” Rodriguez wrote. “However, much of the vegetation throughout the property is of poor ecological value and impenetrable due to the overgrowth and the presence of invasive shrubs and vines.”

When asked for supporting documentation, Rodriguez replied with a general statement about their landscape planning process, but did not provide documentation to back up their assessment of the forest. PPR’s Soukup referred Grid to the foundation for documentation.

On March 6, I accompanied arborist Jacelyn Blank as well as a colleague of hers who prefers to remain anonymous. The two tree experts and I scrambled over downed trunks of tulip trees, beeches and white and red oaks. We waded through thickets of twigs that until recently had been more than 100 feet up in the canopy.

“Many of them are native species that are really mature,” Blank says. Some had obvious patches of rot that might have made them vulnerable to fall over in a storm, the sort of weakness that could prompt a landowner to cut down a tree. In the middle of the woods, however, the only thing a falling tree would hit would be other trees.

I asked the foundation about how tree removal was communicated to the public. According to Rodriguez, “the public response throughout the engagement process has been overwhelmingly positive, with widespread support for revitalization efforts.”

Rodriguez specifically mentioned a January 2022 town hall meeting, “during which time the Foundation shared site preparation plans, including removal of invasive species and trees.” The phrasing is important here. Who wouldn’t support removing invasive species and trees?

Ripple effects

While the community outreach, limited though it may be, has been focused on the neighborhoods directly surrounding the golf course, the impacts of the tree clearing will be felt downstream.

Cobbs Creek flows into Darby Creek at the western edge of the flood-prone Eastwick neighborhood, which has been the site of environmental justice organizing by residents.

“No one from the foundation reached out to the Eastwick Community to discuss the clearing of the trees,” Carolyn Moseley, President of Eastwick United, wrote by email. “I only learned of it by word of mouth and an article that was published. It is my hope that someone will reach out to us to discuss this matter as there is a potential for adverse impact on the Eastwick community.”

Although the City of Philadelphia owns the land, a sliver of the golf course to the south of Cobbs Creek is in Delaware County. Parkview Road runs for about half a mile along the golf course in Upper Darby, separated by the easily-crossed tracks of SEPTA’s Norristown High Speed Line.

“I didn’t hear anything via Upper Darby,” says Laura Wentz, vice president of Upper Darby Township Council, who lives on Parkview Road. “I saw them clearing the trees along Haverford Avenue and freaked out. I saw later they were cutting down trees farther into the park, and now they’re doing it behind my house.”

Temwa Wright, a resident of the Cobbs Creek neighborhood and a member of the Cobbs Creek Ambassadors, a group that conducts cleanups and restoration work in the park, was also taken by surprise.

“It’s crazy, so many trees cut down,” Wright says. After being involved with the city’s TreePhilly planning process as well as Rebuild, the city’s program to renovate park and recreation center infrastructure, Wright says she would have expected the city to reach out about extensive tree clearing nearby. “I don’t care about the foundation. I live in the city, and I want to hear from the city government.”

The Impact Center, an organization based in Haverford that connects youth from the Main Line with volunteer opportunities in Philadelphia, has merged with the foundation to conduct outreach and provide educational programming for the golf course, according to documents attached to the golf course lease agreement. The Impact Center representatives have not yet responded to a request from Grid for comment about their outreach activities. From their website, it is unclear whether they have ever led a community outreach process or administered educational or youth development programming in West Philadelphia.

You work for the people who got you in office, not the people who put money in your pockets.”

–India DiValerio, Overbrook Park North resident

The Cobbs Creek Foundation’s website and other outreach materials promote the proposed community impact of the golf course, including golf teams sponsored at local high schools, golf course maintenance training programs for local teenagers, and educational programs offered at schools and at a planned education center on the golf course. In a January 2022 Philadelphia Inquirer article, the foundation says it “will establish robust programming for the Cobbs Creek community” while raising awareness of the course’s past.

An ambitious budget, a declining sport

The educational and community programming planned by the foundation depends on revenue from the golf courses. According to the operating budget included as an exhibit to the lease with the city, the foundation expects the courses to make an annual $1.9 million profit on $9.1 million in total revenue, a margin of roughly 21%. That $1.9 million is what will pay for foundation overhead expenses as well as the educational and other community work.

Of course, the revenue depends on how many people play golf at the courses. The foundation estimates that golfers will play 43,647 rounds per year at the 18-hole Cobbs Creek course and 43,162 at the Karakung course.

According to figures from the National Golf Foundation, in 2019 golfers played 441 million rounds on 16,300 courses, for an average of about 27,000 rounds of golf per course. At two other Philadelphia municipal golf courses, Walnut Lane and John F. Byrne, golfers played 26,078 and 24,234 rounds, respectively, in 2020 (Annual Report, page 15). In Baltimore, which has five municipal golf courses, only one topped 40,000 rounds per year, according to figures from 2013 to 2015 (2016 Request for Solutions, page 7).

Although the pandemic spurred a bump in golfing activity (similar to other outdoor activities), golf has otherwise been losing popularity after a peak in the 1990s. About 30 million Americans golfed in 2006. In 2021 that number had dropped to about 24 million. The rate of course closures has recently slowed, but more courses have closed than have opened every year since 2009. The viability of the foundation’s community and educational programs depends on the new courses bucking long-term national trends.

Golfers only, please

There’s not much you can do on an active golf course besides golf. You can’t ride a mountain bike through the fairways. You can’t walk your dog. You can’t have a picnic on the greens. You can’t walk the trails as you can in other park spaces.

On a December 7, 2021, Zoom meeting about the golf course hosted by Councilmember Jones’ office, William Fraser, transportation project manager with the Clean Air Council, requested that the Cobbs Creek Foundation consider allowing part of a regional multi-use trail (the Forge to Refuge Trail) to run through the course. Enrique Hervada, the foundation’s senior vice president of development, said that flying golf balls would make it unsafe for non-golfers to traverse the course.

Fraser wrote: “It is disappointing that residents and stakeholders were not made aware of the golf course’s plans to remove a large area of trees, which residents enjoy for recreation. The [Clean Air] Council hopes the Cobbs Creek Foundation will pause their construction work to engage with the community and hear residents’ concerns and wishes for this green space, including the potential of a multi-use trail.”

A Philadelphia landscape ecologist familiar with the park system who spoke with Grid anonymously due to the politically-charged nature of the renovation, questioned whether a renovated golf course is a better land use than a forest. “What does the city need right now, a first-class city golf course or tree canopy?” they said. “This city is getting hotter and losing tree cover. What are we going to do about it?”

A park denied

It does not appear that the golfers behind the renovation project, the Cobbs Creek Foundation or city leaders ever asked the community what they would like to see on the 350 acres of parkland that, for at least 30 years, will be off limits to them, unless they pay $68 to play golf on it.

“The Cobbs Creek Foundation may point to numerous engagements with stakeholders and city officials but engaging and advising proximate residents and the environmental stewardship [and] advocate community requires significant effort and intention,” emailed Kiasha Huling, the director of University City Green (UC Green), an organization that promotes tree planting in West Philadelphia. “The Cobbs Creek Foundation is not uncommon in suffering from inadequate outreach, communications and inclusionary practices in development. West Philadelphians are unfortunately familiar with environmental development happening in their neighborhoods, seemingly without their inclusion or consideration.”

At the edge of the woods on Wyndale Avenue, an old Fairmount Park Commission sign reads “Wyndale Gardens and Trail Entrance.” Behind the sign is a patch of grass now used by neighbors as a picnic and gathering space. The gardens disappeared as the neighbors who maintained them grew older, and the trail has been blocked for several years.

“When we first moved up here, my husband and I and the kids used to walk that trail. You could get to and from other parts of the park,” DiValerio says. About five years ago, “they cut down a tree so you can’t go down there. I don’t know why they did that.”

I asked DiValerio what she would like to see in the public land at the end of her block. “I would have said I’d like to see it as a park. That’s one of the reasons I moved around here,” she says. “I’m not a person to pull up race, but I think if this had been a white neighborhood that would not have happened.”

Thank you for this comprehensive reporting. I am incredibly sad and infuriated at reading this. What next, what can be done to help this community? Speechless.

My name is Nicole Chandler founder of Keep Royal Gardens Beauttiful/ Royal Gardens Association. Since 29 October 2005 it has only been my organization and the volunteers produce from my organization that’s been volunteering with maintaining the perimeter of the Cobbs Creek Golf Course, Rose Playground and Morris Park. It’s astonishing to me to see all these people and other so-called Cobbs Creek organizations that’s trying now to stake some claim to this green space now that stakeholders have invested millions of dollars to its restoration. There is no such existence of a golf course existing in a woodland area that’s open for professional golfing purposes. If the restoration project is assumed to be completed with success then it is expected for the overgrown forestry to be diminished. My question is where is the funding going once the down lumber is sold to mill works??? As usual City Councilman Curtis Jones Junior is always stealing my volunteer efforts and giving the revenue to another organization that had nothing to do with the restoration or maintenance project to begin with. He did the exact same thing to me and my organization with Rose Playground. After I cleared the overgrowth of vegetation throughout Rose Playground and brought it back to life, he then gave the playground and it’s recreation center to the Overbrook Park Civic Association and then allowed them to generated income from it by renting the space out to community members. He is nothing but a user and a con artist and everyone now have so much to say about the forestry coming down, but where were any of you when it needed to be maintained????

I was disappointed in the negative one-sided reporting. This area is desperate for development and investment. Until recently the land was overgrown and a dumping site for trash and even dead bodies. Sure the land could be used for something else, and maybe they should have done more research to figure out the best use of the land, but who should do that work? The government. But they are overwhelmed and incompetent. If people are willing to spend lots of their money and time to improve terrible area that the government has let fall apart, that is not a bad thing. It is much easier to criticize than to actually make things better. I agree that they should not have taken out so many trees, especially the native heritage trees. I blame the government for not enforcing their own rules about heritage trees, or at least taking the time to have a conversation about how to weigh the pros and cons. The PGA tour is talking about bringing an event to West Philadelphia for this course. That is something that this neighborhood can be proud of. Plus, it will attract additional investment that will provide jobs and more economic opportunities in an area that has few. Lastly, we already have lots of public parks in Philadelphia, whereas there are very few golf courses given the 1.5m people. Sure it is true not many people play golf here, but that is partly because they don’t have any opportunities to do so. The foundation has also made plans for educational opportunities and extracurricular programs for youth, which would also help the community. Again – I don’t disagree with everything about this article, but it is very one sided and too critical.

You are 100% correct on all counts. Most of the opponents of this effort are angry people that want to territorially protect their impoverished domain. So sad and blind. Rather than get involved and/or consider the improvements such a project will bring … they just bitch. I guess they need places to dump dead cars or non-functioning washing machines.