Pennsylvania “locks up a higher percentage of its people than almost any democracy on earth,” states the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit in Northampton, Massachusetts, that works to end mass incarceration.

In addition, more than 40,000 Philadelphians, disproportionately Black and Brown, come home each year from state and federal prisons, according to a January 31, 2017 article on Generocity.org about reentry.

The math gets grimmer.

The majority of Pennsylvania’s returning citizens leave prison “ … with limited knowledge of (and little access to) services … ,” according to the 2020 Report of the Pennsylvania Reentry Council. The reentry council, under the auspices of Attorney General Josh Shapiro, seeks the successful reintegration of returning citizens. “Small wonder … that 67% of all returning citizens end up incarcerated again within three years’ time,” the report adds.

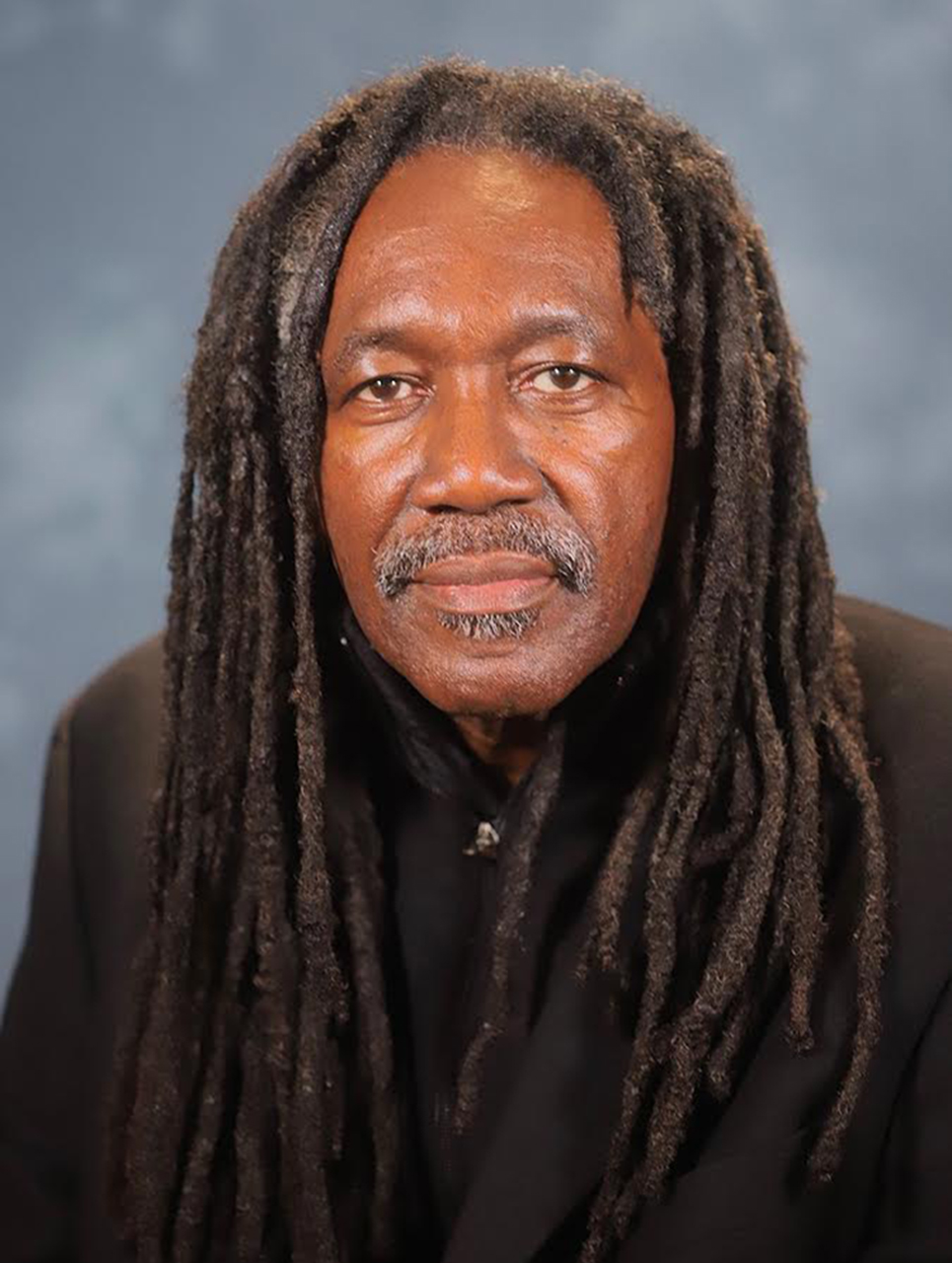

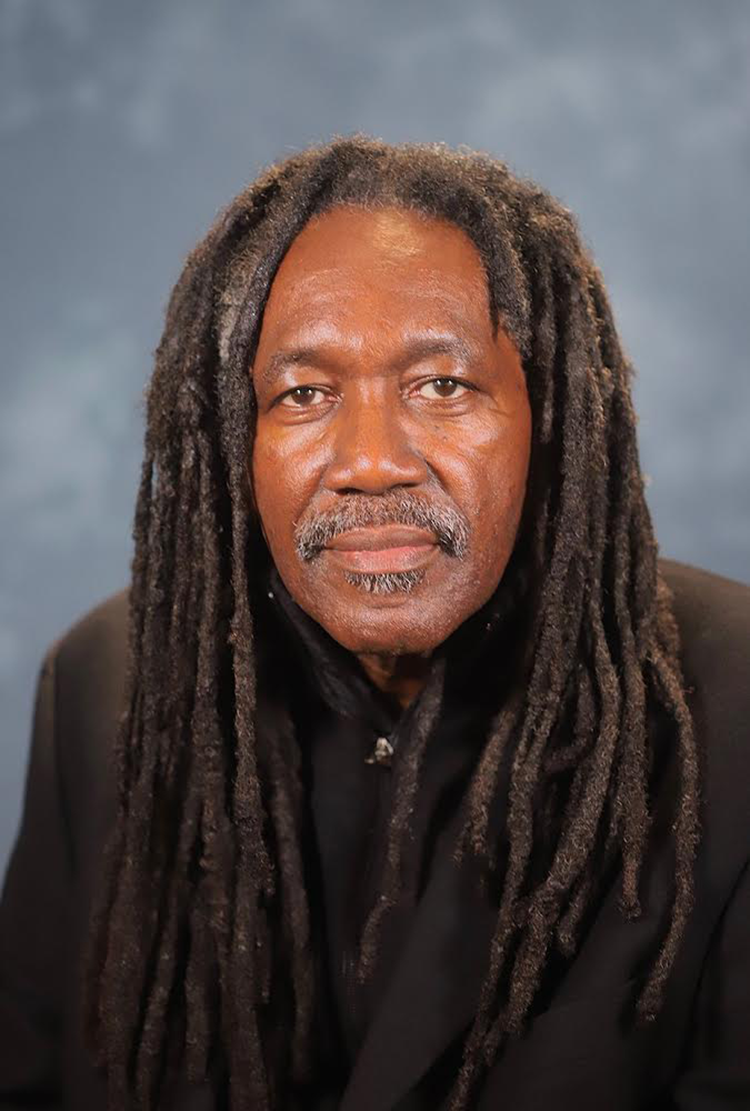

Suffice to say J. Jondhi Harrell, 66, the founder and executive director of The Center for Returning Citizens and the Community Healing Center, is fighting tough odds.

The center, a Germantown Avenue-based nonprofit that has been helping returning citizens and their families since 2012, wants better outcomes.

“Reentry is hard work,” says Harrell. “Lots of times returning citizens come to us in crisis. There’s no food in the house or no electricity. We talk with them one-on-one and then make referrals for housing, food, employment and other services they need for a smoother transition.”

Born in New Jersey to migrant farm workers from Georgia, Harrell has the credentials to design effective support systems.

“I spent 25 years in federal prison,” he says. “Seven years the first time and eighteen years the second time, both terms for bank robbery.”

Released two years early from parole for the second sentence because of his outstanding community service, Harrell completed the Goodwill Industries Ex-Offender Reentry Program, earned a bachelor’s degree in human services management from the University of Phoenix and is completing courses toward a master’s degree in social work at Temple University.

Like Philadelphia’s Office of Reentry Partnerships or the Prison and Reentry Services at the Free Library, the center directs returning citizens to services, but its presence in North Philly lets it reach a different demographic, Harrell says.

“Philadelphia is a fragmented city where some folks only feel comfortable in their own neighborhood,” he says. “They don’t go into town because their experience of Center City is courts and police. We provide help here in the community.”

Assata Thomas, chair of the steering committee of the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition, an umbrella agency for 154 groups offering different services, applauds Harrell’s approach.

“People are returning home to neighborhoods,” Thomas says. “They need robust reentry services where they live.”

Many organizations stress getting a job first for returning citizens, but Harrell speaks of a hierarchy of needs and sustainable steps.

“If you’re assured of food on the table and a roof over your head, you can relax and take on the work of reentry,” he says.

That task includes adapting to new conditions.

“If you’ve spent significant time incarcerated, you have to adjust to a changed world. Your parents are older. Your children have learned to live without you. They may resent you for being gone when they needed you,” says Harrell, a father and grandfather. “You wonder how much patience your family will extend to you.”

The center helps families reknit their bonds.

“We have support groups for families with incarcerated loved ones,” Harrell says. “We also have activities for children of incarcerated parents, like visiting The Franklin Institute and attending basketball games. A mom may need a center member who’s doing well to mentor her son. We arrange for that too, and for help once the family is reunited.”

Reverend Pam McDuffie, pastor of Hosanna Christian Life Center in Frankford, relies on Harrell’s help.

“My son, who’s been incarcerated for some time, will soon come before the Parole Board [for release],” she says. “He plans to start a business based on a music program he developed in prison and uses with other inmates. Jondhi talks with him via telephone to explain the changes my son will find and the steps he needs to take for success. Jondhi also assures my son of continuing support.”

The center encourages returning citizens to look at trauma’s impact on their lives.

“It’s a necessary step to sustain a new life,” says Harrell. “The problems you had prior to incarceration don’t go away. Prison may have intensified them. You do a lot of soul-searching, taking responsibility for past mistakes, for harm you caused. There’s a high level of stress. We’re trying to change ourselves, to do something we haven’t successfully done before.”

Depending on each person’s needs, the center’s referrals may cover psychological counseling, financial literacy, job training, legal aid, addiction treatment and free or low-cost yoga classes.

The center claimed a broader community role when the pandemic hit.

“We opened, and still operate, a food pantry on Fridays, and we deliver boxes of food on Fridays, too,” says Harrell, noting that the center’s current location is ideal for storing food, but that he’d like to share offices with a church or community center to run programs on site.

“On average, we provide food for 8,000 people a month,” he says. “Volunteers make it possible.”

One volunteer, Betty, 59, of Germantown, does, “ … whatever needs doing. I clean the building, organize shelves and distribute food on Fridays. A lot of people don’t have the income to buy food.”

Karl Erikson, 65, the center’s landlord, also lends a hand. “It’s a good use of my time to assist Jondhi in helping people,” he says.

Ali, 33, a poet and songwriter, puts canned salmon on pallets. “In my childhood, I went without food sometimes,” he says. “I volunteer because I don’t want other kids to go hungry.”

Helga, 62, who can greet people in English or Spanish, volunteers on Fridays. “In the afternoon I take food boxes to students at Olney High School.”

Harrell emphasizes that volunteers like Helga are sent to deliver food throughout the city. “We don’t limit ourselves to North Philly,” he says.

When it comes to bettering odds for returning citizens, Harrell explains that formerly incarcerated people themselves must spearhead change.

“Our struggle has to be led by us,” he says, “just as people with handicaps fought to have the Americans with Disabilities Act passed.”

Some returning citizens have already become activists, Harrell notes. Philadelphian Hassan Freeman, who spent time in prison, developed Focused Deterrence, an effective strategy for reducing gun violence.

“Returning citizens are active in many areas of life in Philadelphia,” Harrell says.

While Harrell and others work on the frontlines, they seek allies.

“We get by on small grants and donations, but we would welcome financial help as well as volunteers.”

For more information, visit tcrccommunityhealingcenter.com, call (215) 791-0645 or email jondhi@gmail.com.