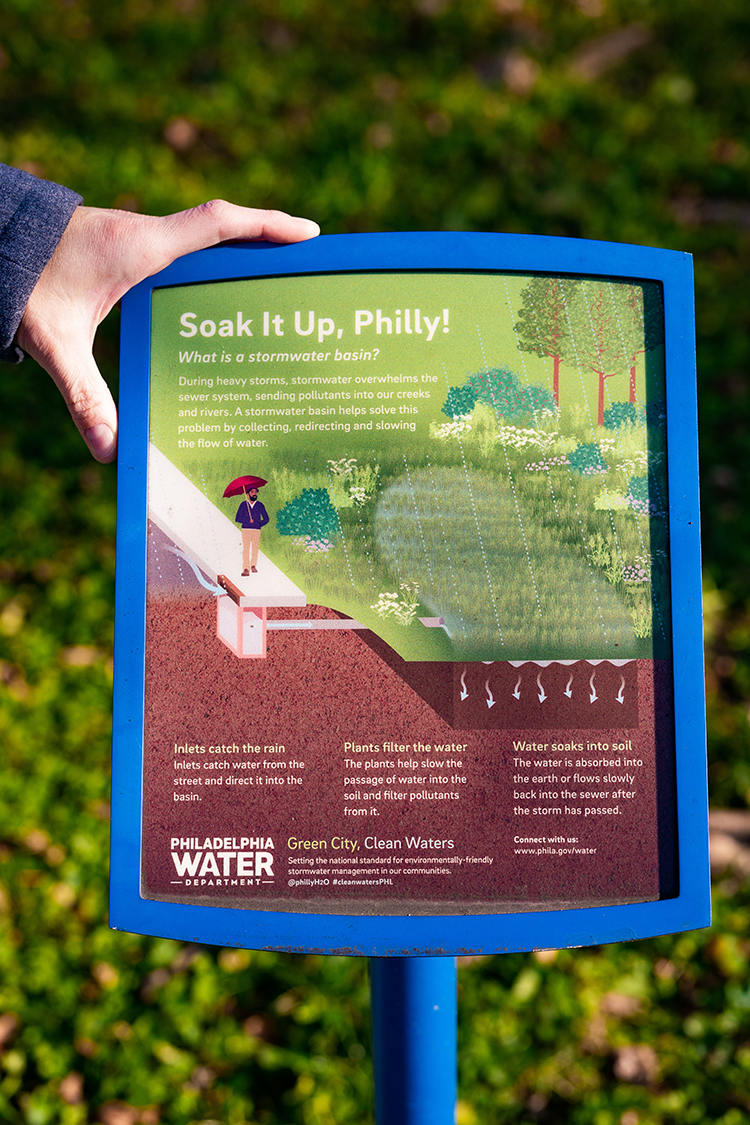

This year, the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) celebrated 10 years of Green City, Clean Waters (GCCW), a 25-year plan that seeks to improve water quality in our creeks and rivers by using rain gardens, tree plantings and other green stormwater infrastructure to soak up stormwater.

Sixty percent of our city is served by an old combined drainage and sewer system. The runoff from heavy rains often overwhelms this system, triggering releases of raw sewage, aka combined sewer overflows, or CSOs, which pollute our waterways and violate the federal Clean Water Act.

At the end of November I had the chance to talk with Marc Cammarata, PWD’s deputy commissioner for planning, about the accomplishments of GCCW and what we can look forward to in the next 15 years.

This interview has been edited for length, clarity and style.

What is green stormwater infrastructure?

It’s an approach for managing urban stormwater using nature-based practices, trying to manage rainfall where it’s generated, using approaches that try to mimic the natural environment.

Sometimes you may see rain gardens, surface vegetation or street trees. Sometimes you may just see the trees because we have subsurface infiltration trenches. You may see green infrastructure presenting itself as a green roof on a building.

Why use green infrastructure and not just “gray infrastructure,” as in pipes and tanks?

It’s never green or gray. It’s always green and gray. We strategically use these natural practices to supplement and augment the traditional infrastructure.

Our sewers are stressed and they continue to be even more stressed in a changing environment, as we see more intense and frequent precipitation events. What this infrastructure allows us to do is keep that water from even making its way into the pipe. If you manage water once it makes its way into the pipe it becomes almost a waste product at that point. So it really is kind of a philosophy change. ‘How do we protect our infrastructure?’ We treat stormwater as a resource instead of treating it as a waste product.

PWD is celebrating the 10 year mark in a 25-year plan. How far along are we in solving our stormwater problem?

In a typical year, we discharged about 14 billion gallons of combined stormwater and sewage. That’s not what was collected and treated—that number was much bigger—but what we actually couldn’t handle through collection and treatment and had to be discharged. We’ve reduced that volume by about two or two-and-a-half billion gallons in the 10 years we’ve been implementing the program.

Are we seeing an impact yet on the waterways where the combined stormwater and sewage is discharged, perhaps with the species of animals that are sensitive to water pollution?

That’s always a challenging question to answer because the challenge is not just improving the quality of the water making it to the stream but making sure the stream itself is conducive to supporting the ecology and aquatic life. We are committed to doing natural stream channel design as a companion tool, to re-engineer the stream environment to be more conducive to the return of beneficial species.

Water system planning is often retrospective, basing plans on historic conditions. How is the PWD’s 25-year plan to cope with stormwater runoff taking climate change into account?

I like to say that climate change is water change. Whether you have more of it, less of it or more intensity.

We’ve always thought about a changing water environment and how we need to think about it holistically: how we manage for the increased precipitation and flooding goes into pipe sizing or treatment upgrades or inlet installations to mitigate localized flooding.

We also think of it as how to protect our source water, what’s happening with withdrawals or drought conditions upstream. We think about its water quality impact, whether that’s raw water or treated water. We’ve always thought about these kinds of perturbances in our water resources, in our water environment and how we factor that into our planning.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I want to express gratitude for the number of individuals that have helped change the way we think about stormwater, whether that’s the academic community, the nonprofit community, the professional service community, the artists, engineers, planners and the neighborhoods. In order to implement green infrastructure at scale it takes everybody to have a voice, to have an opinion and to be part of that process.

It’s great to read the thought of Marc Cammarata on green infrastructure. Very informative post, thanks for sharing!