In 2013 the School District of Philadelphia closed 23 schools, including a massive gray stone building on South Ninth Street, the Edward W. Bok Technical High School.

In an unexpected twist, the development and design firm Scout bought it for $1.75 million and has been gradually repurposing it into a sanctuary for creatives since July 2015. Seven years later, BOK is home to more than 225 small businesses and organizations.

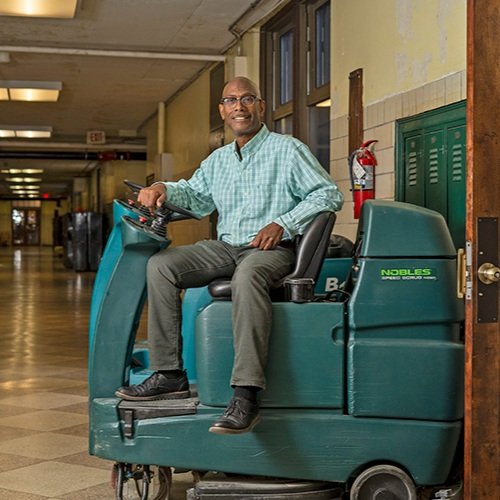

“What is this place?” asks Emmanuel Scipio, BOK tenant and founder of Scipio’s Commercial Cleaning. “It’s old and looks like a school, but it’s not a school. I don’t know the vision that Lindsey had. I don’t know what this chick was thinking, but it’s amazing.”

Scipio is among some of BOK’s long-term tenants. The South Philly native started his cleaning company in 2014 and says he received a call from Scout in 2017. Scout Managing Partner Lindsey Scannapieco was looking to contract Scipio to clean the BOK Bar, a popular watering hole on the building’s rooftop.

Scipio knew this building well—he’s an alumnus.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he says of the day he arrived to meet with Scannapieco.

The two walked through every floor as Scipio reminisced about his high school days. In addition to accepting the contract to clean the bar, he found a place to house his business. Today, with the building finished, Scipio says Scout’s work in revamping the building is remarkable.

“We’ve really had to be laser-focused on making this building work … ”

— Lindsey Scannapieco, Scout Managing Partner

“The school still looks like a school, but from the time that I was in here, I really don’t see it anymore,” Scipio says.

It’s no accident that the 340,000-square-foot shared workspace kept classroom numbers on the door, lockers in the hallway and occasional graffiti throughout the hallways. Scannapieco says Scout bought the former school with these plans in mind.

“When we submitted our bid for this building, we said that what we would do is try to reuse the infrastructure here that was a part of this vocational school and see how that infrastructure could be valuable to different businesses,” she says.

Unique and Resourceful

Scannapieco says that while Philadelphia has several shared workspaces and offices, including Pipeline, Task Up and WeWork, she believed the city needed a shared workspace for “dirtier” businesses, rather than another Class A or B office building.

“I think oftentimes creative makers and artists get put to the fringe of what’s an occupiable building,” she says.

An old vocational school was the perfect backdrop for this vision. Classrooms designated for cosmetology and culinary arts would suit businesses like hair salons and bakeries. The former school was built in 1936, funded by President Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration. When it opened its doors in 1938, 3,000 students from all over Philadelphia attended to learn a wide variety of trades.

“I think that one of the things that makes this building special is that it was made to accommodate students from various subjects,” Cacie Rosario, BOK’s marketing and communications manager, says. “Like wallpapering and auto mechanics and bricklaying. The classrooms are outfitted for majors of study like that.”

With this history in mind, Scout began its redevelopment cautiously in 2015. The team was looking for businesses whose needs would naturally meet what each classroom could offer. Scannapieco met with neighbors and learned many were running businesses out of their homes and would benefit from a space nearby.

“They said, ‘Oh my gosh, my living room is exploding,’ or ‘My workshop in my basement isn’t working’ or ‘I would just love somewhere close to where I live to be able to work that’s affordable,’” Scannapieco explains. “And that’s kind of how it started.”

Today, 71% of the building’s occupants are residents of South Philly.

Scannapieco says the ability to walk to work is a considerable amenity.

“I think that that has a huge impact on not only people’s mental health but also the health and the wealth of their community,” she says.

Makers and Doers

Conscious Cultures founder Steve Babaki started his gourmet vegan cheese business in 2018. Before taking over a friend’s lease at BOK, he had been working out of a yoga studio’s basement, and before that, his home. Babaki says getting a space at BOK was the beginning of his professional career.

“They got me legit,” he says. “I no longer had an illegal business.”

Today, Conscious Culture’s business is booming. The cashew-based cheese is sold throughout the United States, including California, New York and Delaware. The company has also been featured in the New York Times, the Philadelphia Inquirer, VegNews and in the pages of Grid (#134, July 2020.)

A similar story follows Second Daughter Baking Co., also fairly new to BOK. The sister duo, Rhonda Saltzman and Mercedes Brooks, began their bakery out of their mother’s kitchen in Overbrook. Last year the sisters started reaching out to find a suitable location that met their needs, but the pandemic threw a wrench in the process.

“We called different bakeries, catering companies, you name it,” Saltzman says. “We called everywhere to figure out what would make sense for us and our usage. Everyone, literally every single person, told us no.”

But BOK was actively trying to help creatives during COVID-19, and they told the sisters yes.

“[It] was really that yes that set our business on this course to what it is today,” Saltzman says. “Without it, I don’t know if we would have achieved any level of notoriety or growing success.”

Second Daughter has been featured in the Inquirer, Philadelphia Magazine and Grid (#143, April 2021), and recently prepared an order for the Philadelphia Eagles.

Paving the Way

After almost two years of the pandemic, BOK and its tenants are going strong. Though many small businesses went under during the pandemic, Rosario says the BOK turnover rate was low. Between April 2020 to April 2021, only 10% of units in the building turned over.

OK’s low turnover was partially due to its rent relief program. Scout received $138,000 in Paycheck Protection Program funds in April 2020. They began deferring rent for tenants and assuming the costs of some tenants’ rent, fully or partially. After receiving 118 applications, Scout provided some level of support to 94% of its 200+ tenants.

“Even though obviously everyone took a big hit … overall, we tried to make sure that we would really just meet with tenants on a person-to-person level and see where they were at,” Rosario says. “Seeing what things looked like for them.”

In the midst of the pandemic, BOK also managed to expand. Opening up its sixth floor in the fall of 2020, it managed to welcome around 25 new tenants.

Scannapieco notes the BOK building still has a few final spaces under construction today. Still, with its level of leasing success, one may wonder whether Scout envisions revamping buildings elsewhere to construct more unique spaces that meet the needs of creatives.

Scannapieco says Scout has been approached by cities like Detroit, Baltimore, Newark and Memphis that are looking to repurpose older buildings to sustain small entrepreneurs, makers, artists and nonprofits.

For the moment, Scannapieco says, Scout remains focused on BOK and ensuring that the space accomplishes its initial goals.

“For us, this was a huge leap of faith. And for so many other people who believed in us from the beginning—or maybe didn’t believe in us,” Scannapieco says. “We’ve really had to be laser-focused on making this building work … but we’re certainly looking at other opportunities because I think that a lot of places would benefit from spaces like this.”