Wei Chen grimaces and shakes his head when talking about how it’s been a hard year for many in Philly’s Asian community.

“It’s at the point where many of our elders are afraid to go out,” says Chen, 30, civic engagement coordinator for Asian Americans United (AAU).

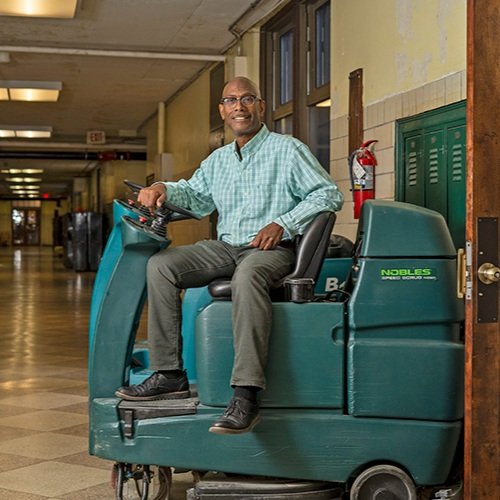

Wei Chen of Asian Americans United under the Chinatown Friendship Arch at 10th and Arch streets. Photography by Drew Dennis.

The organization was founded in 1985 to join people of Asian ancestry in honoring their culture and fighting oppression. Verbal and physical assaults on people of Asian heritage, who constitute about 8% of Philadelphia’s population as of 2019, surged by 200% from 2019 to 2020, says the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, at California State University, San Bernardino.

“Many people don’t report incidents because they don’t know where or how, or they don’t speak English.”

— Wei Chen, Civic Engagement Coordinator for Asian Americans United

This year on Easter Sunday at 11th and Filbert streets, a man hit a 27-year-old Asian woman in the face so hard in an unprovoked attack that she had to go to Jefferson University Hospital. In early June in Mayfair, two teenagers randomly punched a 17-year-old Chinese American student. A week later, Wei Lin, 28, the owner of a Chinese takeout restaurant in the Feltonville neighborhood of North Philadelphia and the father of two small daughters, died days after a stranger punched him in the head.

“That’s probably only a sliver of the attacks,” Chen says. “Many people don’t report incidents because they don’t know where or how, or they don’t speak English.”

AAU, VietLead and other Asian organizations are working to promote healing from current fears and grief as well as historic trauma.

Philadelphia gave its first Asian residents an uncertain welcome almost 200 years ago.

By the 1840s, Chinese people were living and working here after Philadelphia merchants began sailing to Canton to buy tea and silk in the 1700s, according to “Walking on Solid Ground,” a book by Shu Pui Cheung, Shuyuan Li, Aaron Chau and Deborah Wei that was published by the Philadelphia Folklore Project in 2004.

In the 1870s Lee Fong ran a laundry near 9th and Race streets, then a low-rent district. Fong’s cousin, Lee Wang, soon opened a restaurant nearby, the book says. Those businesses helped to anchor the new community.

On the national scene, from 1863 to 1869, some 15,000 to 20,000 Chinese laborers worked on the mammoth, grueling construction of the western leg of the transcontinental railroad. Many history books sweep aside these men, who were denied citizenship.

Racism and an economic slump led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited the immigration of Chinese men. (Chinese women had been banned from immigrating in 1875.) Congress repealed the act in 1943, about two years after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued an executive order that uprooted people of Japanese ancestry, including U.S. citizens, and incarcerated them in concentration camps from 1942 to 1945.

Chen believes that the economic and emotional ravages of COVID-19 have spurred the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes.

However, for him current assaults feel like déjà vu. In 2009, when he was a student at South Philadelphia High School, he and his friend Bach Tong organized a boycott by Asian students after 30 of them, including Chen and Tong, were beaten without provocation by 100 of their fellow students.

“I followed Martin Luther King’s nonviolent approach,” Chen says, explaining that bullying and assaults had gone on for months before the mass attack.

“Chen’s action changed how we addressed bullying,” says Otis Hackney, now the city’s chief education officer and South Philly High’s principal from 2010 to 2015. “The school’s culture changed.”

Hackney adds that students can now report incidents in their first language, and that the school added an Asian history elective to the curriculum.

Today, AAU and VietLead have become hubs of healing anti-Asian violence and racism in Philadelphia. After the March 16 murder of six Asian women in Atlanta, the AAU became a rallying site for Chinese, Cambodians, Koreans, Indians, Indonesians and other people of Asian ancestry. They crossed ethnic and linguistic lines to make a common cause against anti-Asian violence, Chen explains.

“AAU coordinated a citywide vigil after the shootings,” he says, noting that they held online town halls to address hate crimes.

“We also did a series of online teach-ins about the history of the Asian experience in Philadelphia,” Chen says.

AAU, VietLead and other organizations have cooperated to produce a safety booklet in several Asian languages on how AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) can protect themselves, access victim services and receive mental health support.

Chen emphasizes that Asian Americans and African Americans support each other in antiracist work.

“AAU has always been an ally in the fight for justice for all people of color,” he says, “not just Asian Americans. We tie our struggle to Black Lives Matter because this fight can’t be done without allies. We’ve seen huge support from the Black community.”

VietLead also believes in combined strength.

Nancy Nguyen, executive director of the organization, says ethnic and racial division and animus is baked into our society.

“The lack of ways to process the trauma of racial bias exacerbates this. How are people who’ve experienced violence supported? What therapy do they have to process the harm done?” she asks. “The best way to ‘deal’ with this requires approaching this problem on multiple fronts: interpersonally, we should reach out to each other, the way so many have in mutual support during the pandemic.”

On one wall of its South Philly headquarters hangs a poster that dissects anti-Blackness. Near it is a painting expressing Black and Asian solidarity. VietLead aims to “to develop leadership in the Vietnamese community in solidarity with other communities of color towards improving health [and] increasing self-determination.” For example, VietLead partnered with Juntos, a community-led Latinx group, in offering COVID-19 vaccinations.

“I hope that Philadelphia residents, all of us, can come together and push for more funding for programs centered on healing,” Nguyen continues.

AAU recently joined the Yellow Whistle campaign. Chen and volunteers have walked the streets of Chinatown and other parts of the city, giving out thousands of yellow whistles that people can blow in case of danger.

“In America, yellow has been weaponized against Asians as the color of xenophobia,” the organization’s website says. “The Yellow Whistle is a symbol of self-protection and solidarity in our common fight against historical discrimination and anti-Asian violence.”

“The yellow whistle helps to promote safety for people of Asian ancestry and for anyone who feels threatened,” Chen says. AAU invites all Philadelphians to blow the whistle on racism and violence.