They needed somewhere to go.

In March 2020, the City of Philadelphia began to disperse the homeless population that had settled around the Pennsylvania Convention Center, citing fears of a COVID-19 outbreak. Then in May, the city cleared the Philadelphia International Airport of its homeless population as well.

In total, 51 people were cleared from the airport, only half of whom accepted assistance from city officials. Another 16 people were cleared from the convention center.

“A lot of these people have had trauma and bad experiences at shelters and don’t want to go to a shelter,” James Talib-Dean Campbell, cofounder of the Revolutionary Workers Collective, explained.

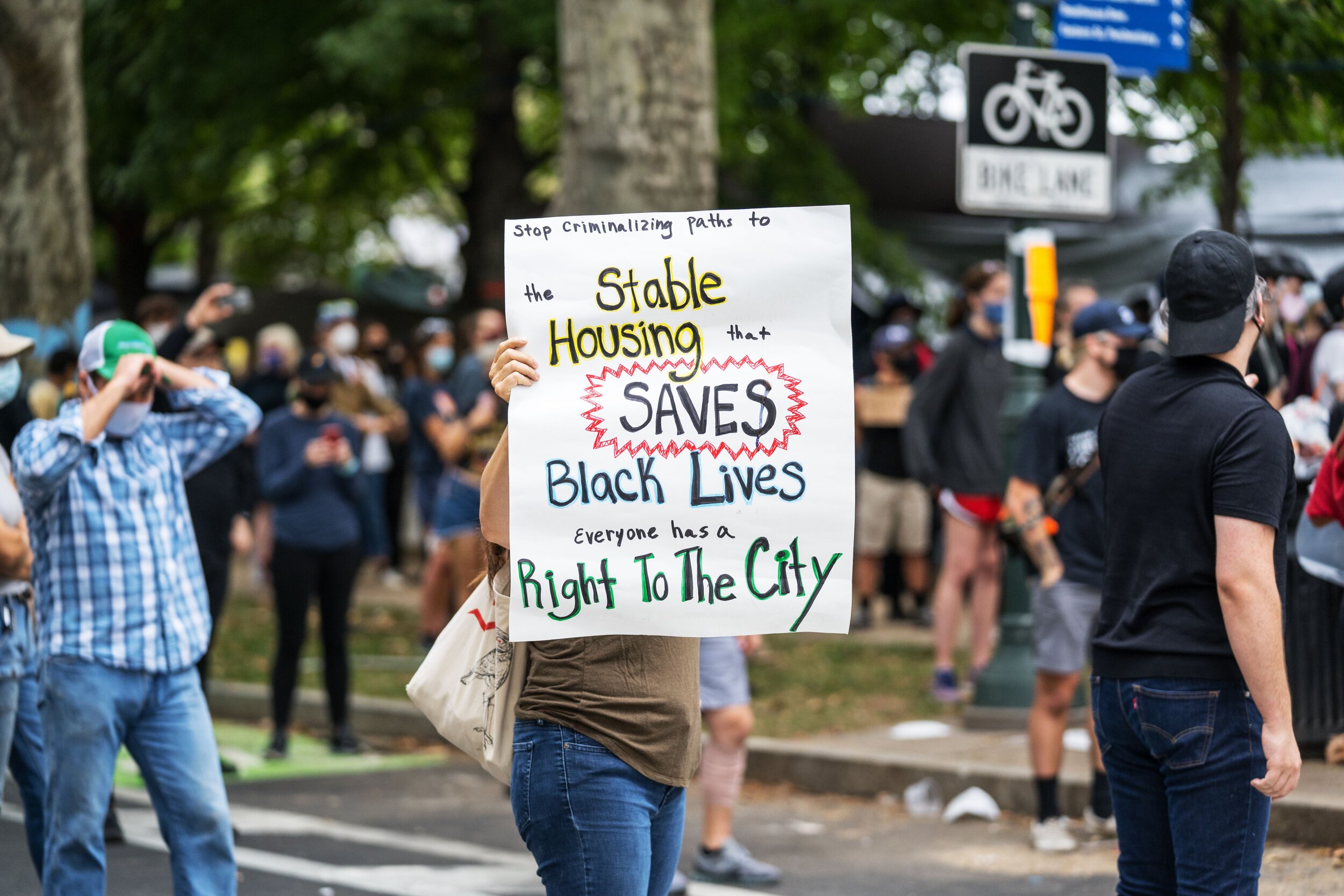

In June, protests erupted across the city in reaction to George Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minneapolis police officers. The homeless sat in the streets as thousands marched, night after night. For them, the circumstances had become untenable. The parks where they’d slept became meeting grounds for protests, the storefronts whose doorways they’d hunkered down in were looted and the National Guard began patrolling the streets.

These are the circumstances that gave birth to Philadelphia’s homeless encampments, which became the saga of the summer—and the fall. What began as five tents has turned into the promise of 50 houses. After taking collective action, Philadelphia’s homeless population, with the help of volunteers and activists, reached a deal to transfer properties from a shuttered federal housing program into a land trust operated by encampment residents.

From mid-June through mid-October, three homeless encampments organized in response to officials’ attempts to evict them on three separate occasions. Over the months, a growing community evolved to meet new challenges like threats of eviction, rain, summer heat and political unrest.

The Beginning: Camp Maroon Talib-Dean

Campbell and Alex Stewart, the founders of the Revolutionary Workers Collective, were instrumental in creating the encampment on 22nd Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway alongside the unhoused. They made up two of the first five tents planted on Von Colln Memorial Field, which they dubbed Camp Maroon.

The original name of the encampment was an homage to “when large groups of Africans escaped to geographically secluded regions to form runaway slave communities” in the 1700s, Campbell explained. “We’ve been doing outreach for a lot of unhoused people. We spoke to a lot of people at the airport and the convention center. Homeless outreach does not give people permanent places to stay … so we set up this protest camp.”

The camp broke ground on June 11 and saw immediate growth and expansion. By June 17, the camp had handwashing stations, a library, a food tent, a garden and consistent donations. On that day, activists held their first press conference with allied community organizers where they announced tragic news: Talib-Dean Campbell had died. His cousin told The Philadelphia Inquirer the death was the result of an overdose.

As a tribute, the encampment on the parkway was renamed Camp James Talib-Dean, or Camp JTD for short.

In Memoriam: Camp JTD

At the same Camp JTD press conference, Jennifer Bennetch, the founder of Occupy PHA (Philadelphia Housing Authority) explained that negotiations for closing the camp had already begun within the first week of opening. Eva Gladstein, the city’s deputy managing director of Health and Human Services, had reached out. According to Bennetch, “[Gladstein] talked about tiny houses and sanctioned encampments, but said nothing about physical properties.”

“Unless they have somewhere to take us, they can try to shut us down, but it’s not going to shut down the movement.” —Jonnell Flowers

Bennetch founded Occupy PHA as a means to protest the PHA Police Department and fight for independent oversight of PHA. She accuses the agency of “operating like a private developer” rather than providing housing. PHA closed the public housing wait list on April 15, 2013. PHA representative Nichole Tillman confirmed on October 21: “The wait list remains closed due to its length and wait time. There is an affordable housing crisis and there is not enough supply for the need.”

“Any meeting with city officials, we’d prefer to have here [at the camp] with the residents so they hear the needs of the residents … they feel like they are too good to come out here,” Bennetch said.

The original list of demands put forth by Camp JTD included things like “accountability for police officers who mistreat the homeless” and the city placing a funding “moratorium against the PHA until all PHA waitlist applicants have been housed.”

Kelvin Jeremiah, CEO of PHA, objected to their demands, and in a WHYY editorial, accused the encampment members of trying to “skip the line.” “Shifting the order of names on a wait list is not a solution but rather an unjust, unethical and illegal act,” he wrote.

Negotiations staggered slowly as the summer months continued.

By mid-July, Camp JTD had grown from five tents to more than 200.

Volunteers created a plumbing system that allowed for better hygiene. A blue hose was strung atop wires and trees, carrying water to a sink placed along the parkway. A generator was donated to provide electricity so residents could charge their phones. The food tent transformed into a full-fledged kitchen, equipped with grills and a microwave. Medics taught Narcan administration for opioid overdoses, and the medical tent was fully stocked with hand sanitizer, masks and condoms.

Camps Teddy and Prosperity

In June, Camp Teddy took root in North Philly outside of the PHA headquarters, drawing attention to PHA’s $45 million building.

Teddy, the 60-year-old man at the eponymous camp at 21st Street and Ridge Avenue, was displaced from the airport on May 26. He was at the homeless encampment by June 13.

Camp Teddy had a modest setup with far less infrastructure than Camp JTD. At its height, Camp Teddy had 40 to 50 tents, making it a smaller community for residents who preferred not to be in Center City around hundreds of people.

“I like it here because it’s quieter,” said Ronald Story, one of the original five to break ground at Camp JTD.

For a brief period of time there was a third encampment named Camp Prosperity, along Kelly Drive in the Azalea Garden behind the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Camp Prosperity was created by Leonard Flowers, who, along with his wife, Jonnell, occupied one of the first five tents at Von Colln Field in June. Camp Prosperity never grew beyond a dozen tents or caused much commotion.

The city began threatening to evict the encampments in early July, but the existence of multiple camps meant that if one camp was displaced, they could retreat to another.

Eviction Notices

On a rainy July 10 morning, encampment residents woke up to find their first eviction notice. It gave them until July 17 to evacuate the park.

“Unless they have somewhere to take us, they can try to shut it down, but it’s not going to shut down the movement,” Jonnell Flowers said of the notice.

Some activists and residents believed that the police were going to sweep the camps overnight, and that the eviction notice gave the city full authority to conduct a raid whenever they wanted. But 9 a.m. on July 17 came and went without any action on the eviction threat.

“I feel like the city only has intimidation and militarization,” Stewart said. “They were gonna come if they were gonna come, but it’s a bad move for the city to come beat us up. It’s a tactic they’ve used in other encampment evictions throughout the year. Most unhoused people are used to having their rights violated, so they get scared and disperse.”

Through July, negotiations stalled and harsh weather tested the durability of tarps and tents, as well as the spirits of those inside them.

Each eviction notice escalated the severity and tension of the situations. The first was zip-tied to a pole in the middle of the night and gave one week for evacuation; however, the second eviction notice only gave 24 hours to leave.

“EVICTION NOTICE: Date posted: 8/17/2020 … If you do not leave this location and remove your property by AUGUST 18, 2020 AT 9:00am,” it read.

The morning of the second eviction attempt, it was about 70 degrees as the sun came up. Hundreds of protesters, activists, medics and volunteers who sympathized with the encampment’s goal of permanent housing mobilized to protect its residents.

The atmosphere on eviction day was warlike. Barricades taken from the neighboring Rodin Museum blocked off 22nd Street, the Whole Foods Market parallel to the encampment was boarded up with plywood and dozens of protesters, many of 30 G R I D P H I L LY.CO M DECEMBER 2020 them dressed entirely in black, were gearing up to stand toe to toe with riot police.

Again, 9 a.m. came and went with no enforcement of the eviction. “Where do we go? Give us housing!” protesters chanted as they walked around the encampment. The presence of hundreds of protesters, along with a strong media presence, kept police at a distance. Police helicopters flew over the encampment but no engagement took place.

The city’s failed second eviction helped strengthen the encampment’s relationship with city leadership and generated more meaningful negotiations. City Council members Kendra Brooks and Jamie Gauthier came out in support of Camp JTD and were present at the second eviction protest.

This was also the birth of a lawsuit that briefly stalled another eviction attempt. Encampment resident Jeremy Williams was vital in protecting the encampment from eviction. He worked with a group of unhoused residents and law students in the dugout of Von Colln’s baseball field, making call after call to city leadership and preparing a lawsuit.

However, in late August, a federal judge gave Philadelphia the green light to “dissolve and terminate” the camps with the caveat that residents would be given 72 hours’ notice. On August 31, a third and final eviction notice for Camp JTD was posted. Encampment residents were given until September 9 at 9 a.m. to evacuate.

By the start of September, a number of encampment residents had decided to move on from the camps and get more secure shelter. Teddy, who helped create Camp Teddy, was granted shelter in a hotel from the city after suffering a heart attack. A devastating mid-August rainstorm flooded and damaged most of Camp Teddy, and a number of residents moved into vacant houses.

Bennetch, of Occupy PHA, became instrumental in organizing as summer turned to fall. Her ongoing battles with PHA over the course of many years prepared her to negotiate with the city.

“They have a $400 million annual operating budget to provide housing and rental subsidies to people in need. It’s their job to house people,” Bennetch says about PHA. Bennetch camped outside of the PHA Building in 2019 to protest the PHA police and PHA policies that displace people. [Editor’s note: the annual budget for PHA in 2020 is reportedly $371 million.]

“Most unhoused people are scared of having their rights violated, so they get scared and disperse.” —Alex Stewart, Revolutionary Workers Collective cofounder

Despite the unrest, PHA representative Tillman maintains that the agency is fulfilling its mission.

“PHA serves over 80,000 of the most vulnerable Philadelphians with an average income of $15,000,” she said. “Although, due to the housing crisis, PHA cannot solve the affordable housing crisis alone.”

The third eviction attempt was more tense than the first two. Numerous employees from SEPTA, License and Inspections and Homeless Outreach, as well as 15 to 20 police cars, surrounded the camp. They were blocked by barricades from the previous eviction attempt, along with new obstructions.

Once again, volunteers and supporters stood guard with the homeless residents. Volunteers ordered U-Haul trucks to protect personal belongings, and residents of Camp Teddy were on walkie-talkies coordinating with Camp JTD.

The Philadelphia police attempted to use members of the clergy as a Trojan horse to precipitate the encampment sweep. When members of the clergy approached the camp, 31 protesters chanted back “Let’s kill Jesus!” and mocked them until they went away.

The mood at Camp JTD remained anxious, and residents were certain that police would raid them overnight.

On the night of September 10, dozens of activists and volunteers slept at the encampment, unsure whether the police and trash trucks would arrive. People sat in tents and played cards, drew murals, drank and smoked weed, waiting for a fight with police that never came.

Following the third eviction attempt, residents of the encampment decided to invite Mayor Kenney to the encampment for brunch on September 14. A press release was issued and a banner was erected reading, “Dear Mayor Kenney: You’re cordially invited to brunch & conversation @ Camp JTD … No violence, no barricades, all solution.” Kenney did not attend.

When asked why, the mayor’s Senior Communications Director Mike Dunn told Grid that over the course of the summer, Kenney had personally devoted many hours toward a resolution.

“He met face to face twice with protest camp organizers and leaders over the summer to hear from them and learn more about their agenda,” Dunn explained. “He then directed top-level staff from the managing director to the deputy managing director for Health and Human Services and director of Homeless Services to develop proposals to address the camp’s agenda and to continue to work with them with the goal of an amicable resolution. Senior city leadership has carried out the mayor’s directive, keeping him informed throughout, and they themselves had many more meetings, calls and emails with camp organizers.”

After a week and a half, the blockade on 22nd Street was lifted for the first time in nearly 40 days.

“We’re willing to compromise. Fifty houses and the street stays open,” said Dave, a younger resident of the encampment. On September 26, rumors of a tentative deal with the city for 50 houses became public knowledge, per a press release signed by Bennetch and the group Philadelphia Housing Action.

As confusion over the 50-house agreement lingered, negotiations to clear Camp Teddy made strides. On October 5, an agreement was made to clear the encampment outside of the PHA Building; the deal put nine houses in the land trust to be repaired and occupied by the residents of Camp Teddy.

The deal ensured that residents of Camp Teddy could opt in to social services from Project HOME or the city, and created a pilot program titled the Working for Home Repair Training Program that’s intended to create housing and job opportunities for those experiencing homelessness through the renovation of long-term vacant structures. Every resident of Camp Teddy opted to take the deal.

One week later, on October 12, PHA and Camp JTD came to an agreement to close down the encampment permanently. The deal included 50 houses placed in a land trust, the development of two tiny house villages, nine bedrooms for individuals in shelters and one five-bedroom house for a family under the existing Shared Housing Initiative program, as well as 32 new Rapid Re-Housing opportunities. Rapid Re-Housing is a program that provides first and last month’s rent and a security deposit, along with two years’ rent for eligible participants.

News of this deal was received with mixed emotions. Some activists say it’s not enough. Residents of the encampment were confused and agitated about the specifics of the deal when they first heard about it, but the camps have been cleared.

What Comes Next?

On the date of the last eviction attempt, activist Tara Taylor made a speech to protesters, the media and their allies.

“The media likes to talk about who the socalled leaders are, they like to talk about what organizations are taking up time on the mic, they like to talk about what the city says they are doing,” Taylor said. “But I’m here to tell you that the foundation of this movement, and of every movement, is the people on the bottom, who are most affected.”

As evictions came and went, the homeless stayed. As activists came and went, the homeless stayed. Through rain and shine, hot and cold, through crises and personal disagreements, a percentage of Philadelphia’s homeless population banded together and kept each other safe during a pandemic. There were fights and attacks, and residents and organizers of the encampments died without learning the fate of their project.

Despite a deal being announced, many encampment residents are skeptical that the city will actually follow through on its promise. Dunn, speaking for the city, told Grid, “The city remains committed to an amicable resolution to the encampment as evidenced by the agreement announced.”

As of November, a fence surrounds Von Colln Field and no tents remain. Several former residents of Camp JTD have moved into houses and some remain in hotels at the expense of the city. Time will tell the state of the homes delivered and the effectiveness of the encampments of 2020.