Death by Another Name

By Constance Garcia-Barrio

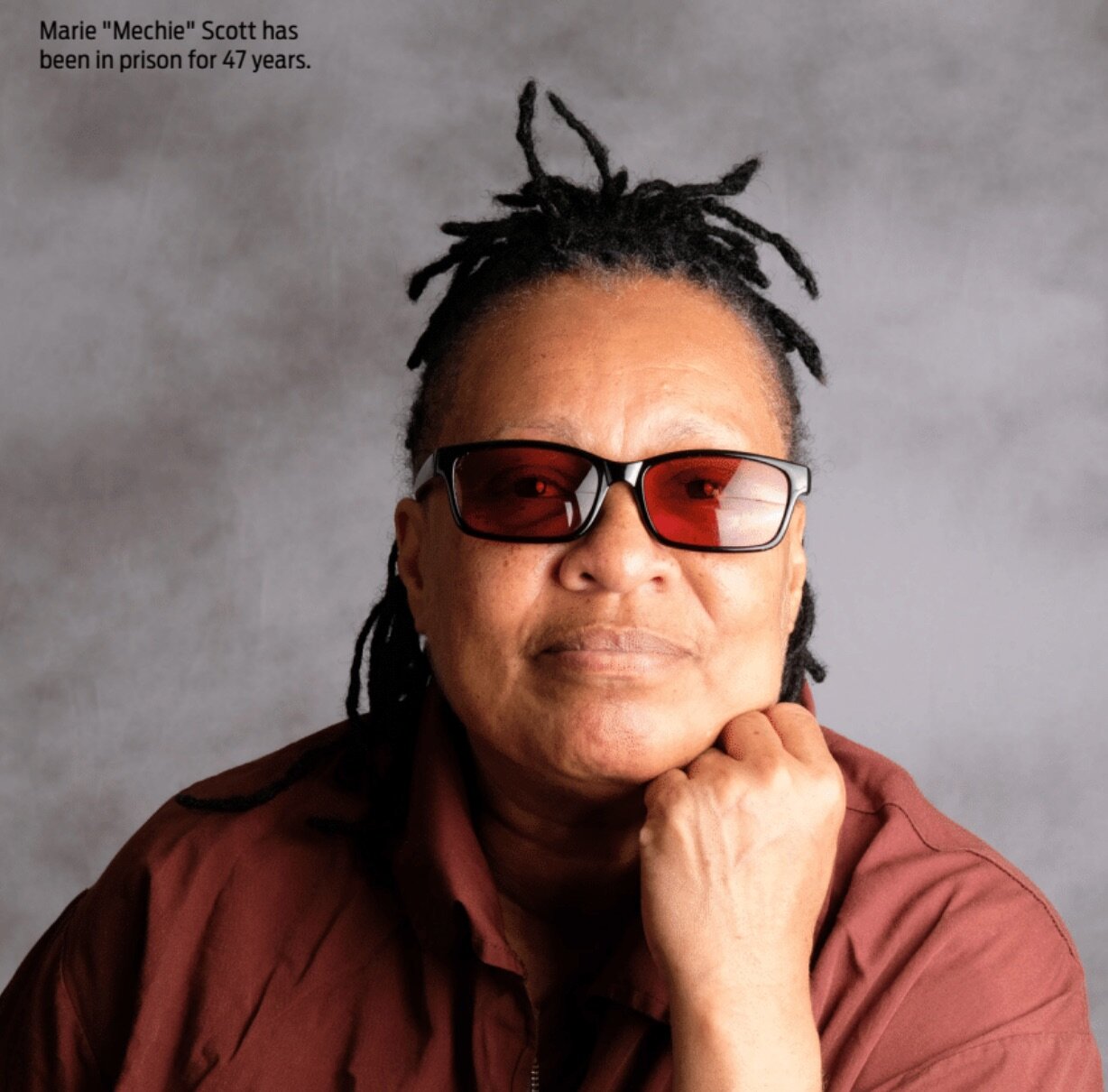

If she served as the lookout during a gas station holdup, Marie “Mechie” Scott, then 19, believed she would get cash to buy the heroin that helped her blunt deep pain.

Raped first at age 5 and repeatedly into her teens, in addition to enduring poverty and homelessness, Scott began drinking at age 9, smoking pot at 14, and using heroin at 16.

At the gas station, things went wrong. Scott’s co-defendant, a 16-year-old boy who had a gun, shot and killed gas station attendant and volunteer firefighter Michael Kerrigan. Scott didn’t know that the youth planned to shoot Kerrigan and never intended that Kerrigan should die, but she was convicted of felony murder, an unintentional death that occurs in the course of committing a felony. Pennsylvania law categorizes such deaths as second-degree murder; different from first-degree murder, a planned killing, and third-degree murder, an unintentional murder or one committed in the heat of passion.

In Pennsylvania, felony murder carries a mandatory sentence of life in prison without parole. Scott has been in prison since 1973. She has served 47 years of her life-without-parole sentence in Muncy State Correctional Institution, in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania.

The Board of Pardons is the only recourse for prisoners like Scott. The board can commute a sentence to allow parole, at least in theory.

Scott has petitioned the board for parole several times. In her nearly half-century of imprisonment, Scott’s accomplishments include earning an associate degree in sociology, completing training as a paralegal, leading peer support groups, writing a play about bullying, working as a sewing machine operator, developing a program for children of incarcerated parents, designing and leading workshops on codependency and developing a coloring book for grieving children.

“I made terrible choices when I was very young,” Scott says. “Mr. Kerrigan would be alive if I had just said, ‘No.’ I’m responsible for his death, but I’m a different person now.

The board of pardons turned Scott down. That ruling came as no surprise in some circles.

“[The Board of Pardons ] is a broken system,” says attorney Kris Henderson, 34, co-founder, organizer and executive director of the Amistad Law Project, an organization whose members include attorneys,

activists and organizers who “advocate for the recognition of human rights of all people.” Once relatively frequent, commutations in Pennsylvania for life-without-parole sentences have dwindled to just eight between 1995 and 2018.

The Board of Pardons seems to sweep aside even expert opinions. For example, it repeatedly rejected brothers Reid and Wyatt Evans for parole. Wyatt and Reid were 18 and 19, respectively, when they carjacked the owner of a popular Center City bar, Leonard Leichtner, using a nonfunctioning gun. They stole $47 from him then dropped him off near a phone booth, as he asked. Hours later, Leichtner died of a heart attack. The Evans brothers didn’t kill him or intend that he should die.

Convicted of felony murder, the brothers, now 57 and 56, have served 37 years. They accept responsibility for Leichtner’s death. They have exemplary conduct records and have completed many rehabilitative programs. They’ve made charitable donations to the Bethlehem School District and acquired skills, such as working with sheet metal, that will help them secure gainful employment.

In December 2019, the Evans brothers sought parole again, one of many such petitions they’ve made during nearly 40 years in prison. Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner sent a statement of support.

Because of “… the low likelihood of recidivism among older people … incarcerated for long periods of time, … the defendants’ age at the time of the incident … and conduct while incarcerated, this office [Krasner’s] did support commutation for both Reid and Wyatt Evans,” the statement read.

Even the DA’s statement cut no ice. The Board of Pardons nixed parole then, but voted in favor of it in September in the face of mounting pressure.

Despite the Board of Pardon’s seeming reluctance to grant life-without-parole inmates a second chance, Scott and others convicted of felony murder may yet leave prison in something other than a coffin. A lawsuit, legislation and grassroots organizing could result in reforms that free them.

On July 8, 2020, the Abolitionist Law Center (ALC), a Pittsburgh-based public interest law firm organized to abolish race- and class-based incarceration in the U.S., filed a lawsuit on behalf of Scott and three other plaintiffs—Normita Jackson, 43, Marsha Scaggs, 56, and Tyreem Rivers, 42—against the Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole.

ALC is co-counseling on the lawsuit with the Amistad Law Project, of Philadelphia, and the Center for Constitutional Rights, of New York City, an organization “dedicated to advancing and protecting the rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

The four prisoners have served a combined total of 125 years for killings that they neither committed nor intended. The suit challenges current laws that deny these inmates a chance for parole, referring to their sentence as “death-by-incarceration” (DBI). Forcing prisoners to die behind bars amounts to “cruel punishment,” the lawsuit argues, something prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.

Pennsylvania stands at an extreme not only in the United States but the world in dishing out DBI sentences, the lawsuit notes.

“Pennsylvania [is] staking a claim as a national leader in the practice of condemning people to die in prison,” Bret Grote and Quinn Cozzens, both attorneys with the Abolitionist Law Center, write in their report, “A Way Out: Abolishing the Death Penalty in Pennsylvania.” More than 5,300 people in this state are serving DBI sentences. Of that number, 1,100 were convicted of felony murder.

About 70% of those serving such sentences are Black, a number out of all proportion to the number of people of African heritage in Pennsylvania.

“Put another way, Black Pennsylvanians are serving death-by-incarceration sentences at a rate more than 18 times higher than that of white Pennsylvanians,” Grote and Cozzens state in the report.

While the state holds a grim record for caging its citizens until they die, Philadelphia has the even more damning distinction of being the life-without-parole capital of the world. Its courts have sentenced some 2,694 people to die in prison, a number that amounts to more than 50 percent of people serving DBI sentences in Pennsylvania, Grote and Cozzens state in “A Way Out.” Those numbers scream that this is a Philly problem: “In Philadelphia, one of every 294 Black residents is serving a sentence of death-by-incarceratio

n,” the ALC finds.

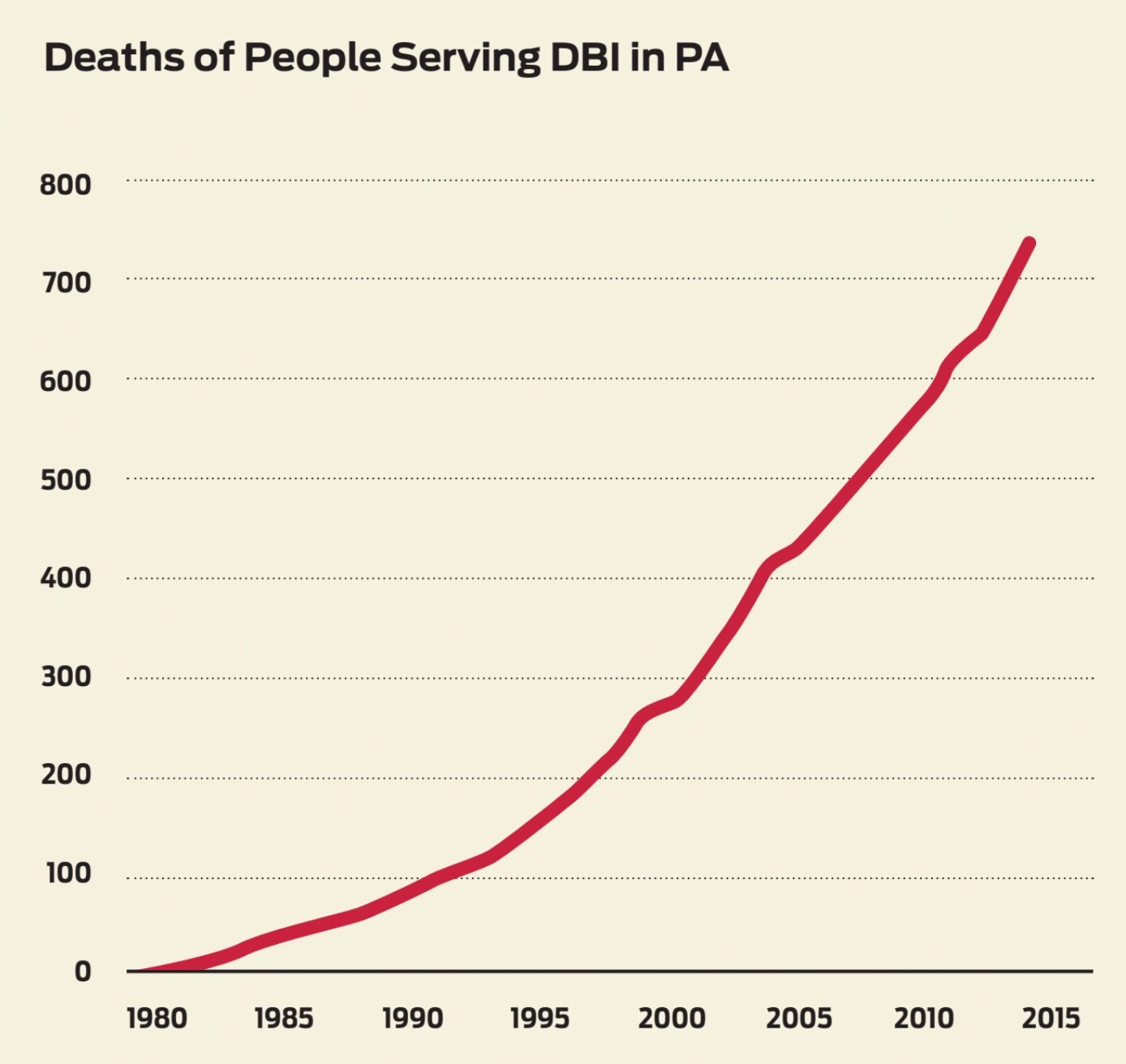

More alarming still, the Abolitionist Law Center points out that the numbers have spiked. In 1974, fewer than 500 people were serving DBI sentences in Pennsylvania. Today’s figures of 5,300 represent a more than 10-fold jump in such sentences.

Racism poisons the criminal justice system, and money may sully it further. The two factors go hand-in-hand, points out Christopher Rabb, 50, state representative for Pennsylvania’s 200th Congressional District, which includes parts of Northwest Philadelphia.

“There are two criminal justice systems: One for the haves and another for the have-nots, and it’s racialized,” Rabb says. “So poor Black and Brown people often end up on death row or serving DBI sentences because they don’t have money for a good defense,” says Rabb, who’s introduced bills for criminal justice reform.

Faith Adams, 58, whose son has been serving a DBI sentence since 2008, agrees.

“People who were to help us financially [with the cost of defense] dispersed,” says Adams, a member of the Coalition Against Death-By-Incarceration (CADBI). “If you don’t have money, you’re screwed.”

Mechie Scott believes lack of funds for a private attorney hampered her, too.

“I had a court-appointed lawyer who didn’t pay attention to any of my ideas about the case,” she says. “I wanted to request a change of venue because my case was so notorious, and I didn’t feel I could get a fair trial here because Rizzo was mayor at the time.”

Often, circumstances seem engineered to lead to life imprisonment.

“With the school-to-prison pipeline, it’s as if everything is set up to get the offender to the place of serving a life sentence,” says Barb Toews, associate professor of social work and criminal justice at the University of Washington Tacoma, and author of “The Little Book of Restorative Justice for People in Prison: Rebuilding the Web of Relationships.”

Besides involving race and class inequities and personal tragedy, DBI sentences put a back-breaking burden on taxpayers, the ALC lawsuit notes. Maintaining older DBI prisoners comes at a huge cost. States would save about $66,000 per prisoner released per year, according to estimates in a 2012 report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), “At America’s Expense: the Mass Incarceration of the Elderly.”

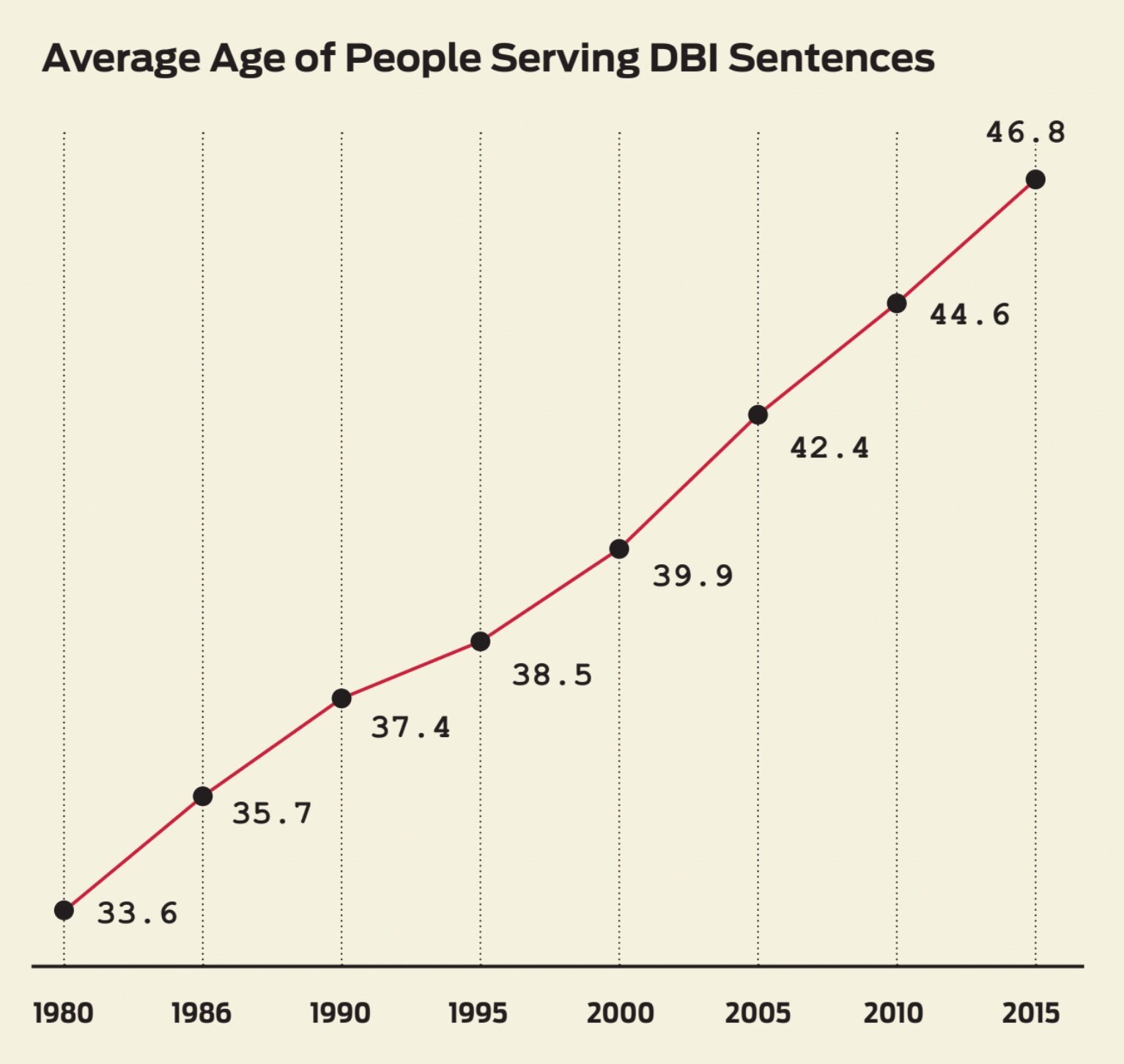

The graying prison population, whose numbers have soared due to harsh sentencing guidelines of the past, may require oxygen, wheelchairs, diapers and insulin—the same care and equipment that elders in the rest of society may need.

“Restorative justice looks at repairing the harm done by the crime. It looks at healing everyone involved.”—Juwan Bennett,a Ph.D. student in TempleUniversity’s Department of Criminal Justice

The ALC lawsuit stresses that allowing parole for people like Scott, who’s nearing 70, would pose no danger to the public.

“… The majority [of prisoners serving DBI for felony murder] are aging or considered elderly by prison standards, with an average of 48 years, and have already spent decades in prison,” it says, “… there is evidence to show [advancing their age] correlates to low recidivism.”

In addition, life-without-parole sentences waste older prisoners’ wisdom.

“I’ve visited seven prisons, and in all of them I’ve seen older prisoners actively mentoring younger ones,” says Rabb. “Once paroled, older returning citizens could talk with members of the next generation at risk for entering prison. Returning citizens may have a more powerful preemptive impact than anything else because they speak from experience.”

Crimes and prison sentences avoided, thanks to the first-hand advice of former inmates would translate into tax dollars saved, Rabb points out.

Henderson, of the Amistad Law Project, makes that point about Marie Scott.

“If Ms. Scott is released, she could be, would be and should be talking with young people about her experience,” Henderson says.

Besides dollars and cents, life-without-parole for felony murder sentences exact an emotional price from prisoners and their families.

“It takes a toll on you when you have a loved one in prison, mentally, physically, emotionally, financially,” says Cee Cee, 61. Cee Cee, a member of CADBI, has a son in prison.

“He went in at 21. Now he’s 46,” she says. “My mother died in 2016 and my sister died in 2017, so now I’m alone.”

Adams, too, has seen a multigenerational impact.

“My son has been in prison since September 18, 2008,” she says. “I walked around in a daze for six years [after his incarceration]. It affected my health. Besides that, my son has a daughter who was 2 years old when he went to prison. When she was smaller, every time our visit with him ended she would fall apart. She’s 14 now, but she still has a level of sadness.”

CADBI member Julie Burnett, 54, currently has five family members in prison, three of them serving life-without-parole sentences. “I want to work on prison reform and restorative justice,” says Burnett, who has turned her anger into activism. “I’m pursuing a master’s degree in criminal justice with a minor in human services.”

The ALC lawsuit and bills proposed by Pennsylvania lawmakers may mean fewer families struggling to provide moral and financial support for relatives sentenced to life-without-parole.

State Representative Jason Dawkins, of Pennsylvania’s 179th congressional district, which stretches through lower Northeast Philadelphia, draws on personal knowledge in crafting bills to eliminate life-without-parole for felony murder.

“I had the experience to see [murder] from multiple angles,” Dawkins says. “I was raised in Frankford in a single-parent home, the youngest of three boys. My oldest brother was shot and killed at 21. My younger brother, by a different mother but the same father, murdered a man at age 16. The man was a drug dealer who’d beaten up his mother.”

Dawkins’ personal perspective puts him in a unique position as a legislator.

“Losing a family member to murder is a tough issue,” Dawkins says. “Some families express empathy [for the murderer]; some want you to stay in prison forever. I thought it important to have a pathway to redemption,” he says. Dawkins’s bill provides for review for parole after 15 years.

“I took a good deal of flack for proposing that bill, and I’m not saying that everyone should be released from prison,” Dawkins says. “Some incarcerated folks should absolutely not come out. They need more help than the system can give them.”

Dawkins feels the bill has a long road ahead. He introduced it in 2016, then reintroduced it in 2017, while Sharif Street, of the third senatorial district, presented a companion bill in the State Senate.

“The bill is still in camera, or being reviewed. I have to figure out what changes can be made so that it’s more acceptable to Republican colleagues while preserving the heart of the bill,” Dawkins says. “This isn’t a sprint, but I never thought it would be. It may take my whole career to see some movement on it.”

While Pennsylvania may take its time, a movement toward ending life-without-parole for felony murder seems to be gaining traction in the United State Congress.

New Jersey Democratic Senator Cory Booker introduced “a groundbreaking bill” last year: the Second Look Act.

It would allow a person who has served at least 10 years in federal prison to ask a judge to take a second look at their sentence to see if they’re eligible for reduction or release. The defendant would have to show that he or she does not endanger anyone, presents no risk of committing crimes, shows readiness for reentry and that a change in the sentence serves justice.

Senator Booker’s bill sounds a hopeful note on the national scene, but Philadelphians need to step up locally, given the city’s callous record of condemning its citizens, especially Black citizens, to die in prison.

“People need to become politically engaged and work with grassroots organizations to ensure that politicians put ending DBI at the top of their agenda,” Grote says.

Successful reentry from prison is more than a matter of opening doors, ALC lawyers state. Former lifers must have a structure that gives them support.

“Decarceration means more than emptying prison beds,” Grote says. “It requires funding social services, employment opportunities, vocational training and other initiatives.”

Wider public knowledge of restorative justice could make a difference in sentencing, Juwan Bennett, 28, a Ph.D. student in Temple University’s Department of Criminal Justice, believes. “Restorative justice looks at repairing the harm done by the crime,” he says. “It looks at healing everyone involved. Sometimes, but not always, that means bringing victims and perpetrators together.”

That said, this reform must start with a political push.

Rabb reminds fellow Philadelphians that you don’t have to be a professional lobbyist to talk with your representatives.

“You have the constitutional right to talk with legislators,” he says. “Church groups, community groups and others can ask for time to present their point of view, but be strategic about your argument. For example, if you’re addressing a Republican legislator, you may have to frame eliminating DBI in terms of fiscal responsibility and the cost of incarcerating the elderly.”

While Scott languishes in prison, her co-defendant in the gas station holdup has been granted parole. As he was 16 years old at the time of his crime, he qualified for relief after a 2012 Supreme Court ruling that barred giving minors mandatory life sentences. Current felony-murder laws allow no such leeway for Scott.

“She’s a great person, warm, caring,” says Amistad’s Henderson. “She’s been in prison longer than I’ve been alive. If one or two circumstances had been different—for instance, if the holdup had happened in another state—she might have been charged with third-degree murder, which allows for parole. The idea that she should die there is appalling.”

That prospect frightens Scott.

“I’ve seen people grow old and sick in prison and not get the care they need before they die,” she says.

But Scott can envision a future where she uses her grandmotherly age and years of imprisonment to good effect.

“I won’t say I want to give back, because you can’t give back a life, but I’d like to continue the work of helping children of incarcerated parents because during my time here, I’ve seen members of the second generation from the same family wind up in prison,” she says. “I’ve also devoted time to help the children of incarcerated mothers and fathers … to honor my victim and the trauma I caused for his children.”

For now, Scott feels the weight of every day behind bars.

“In prison, you’re disrespected by the guards,” she says. “You don’t get visitors because you’re too far away. You hear that your mother passed away, that your sister has cancer. Today, I would say [in court], please give me the death penalty and get it over with.”

Its a terrible injustice these people still in prison. Rivers did not strike the woman in the head. I can’t believe families so vengeful. Let them free.