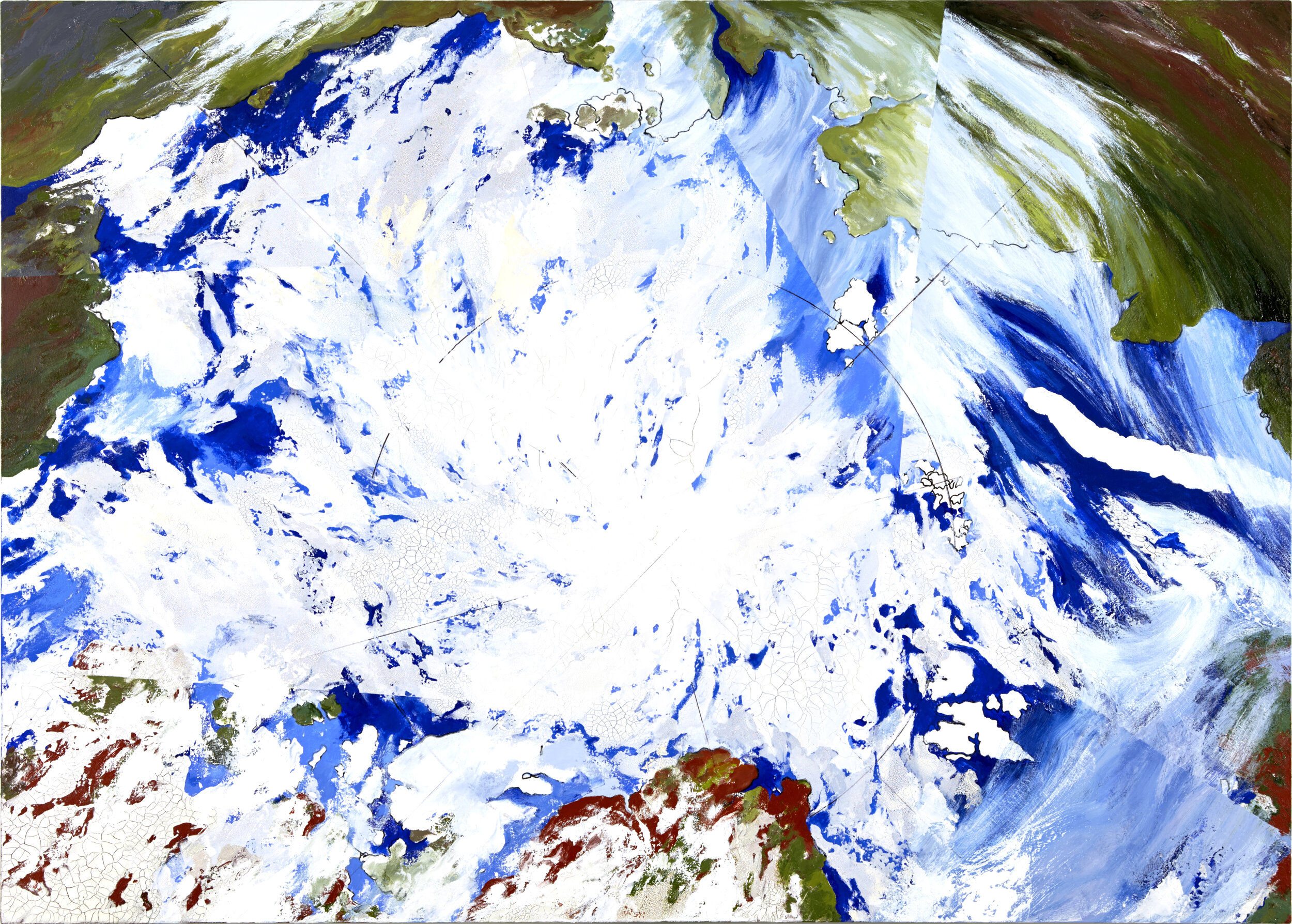

Photo by Nadine Rovner

The Tide is Nigh

By Francesca Furey

With looming fears and anxieties brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak, concerns about climate change or the health of local watersheds might seem secondary. That is an illusion. As Thomas Fuller, a 17th-century physician, wrote, “We never know the worth of water till the well is dry.”

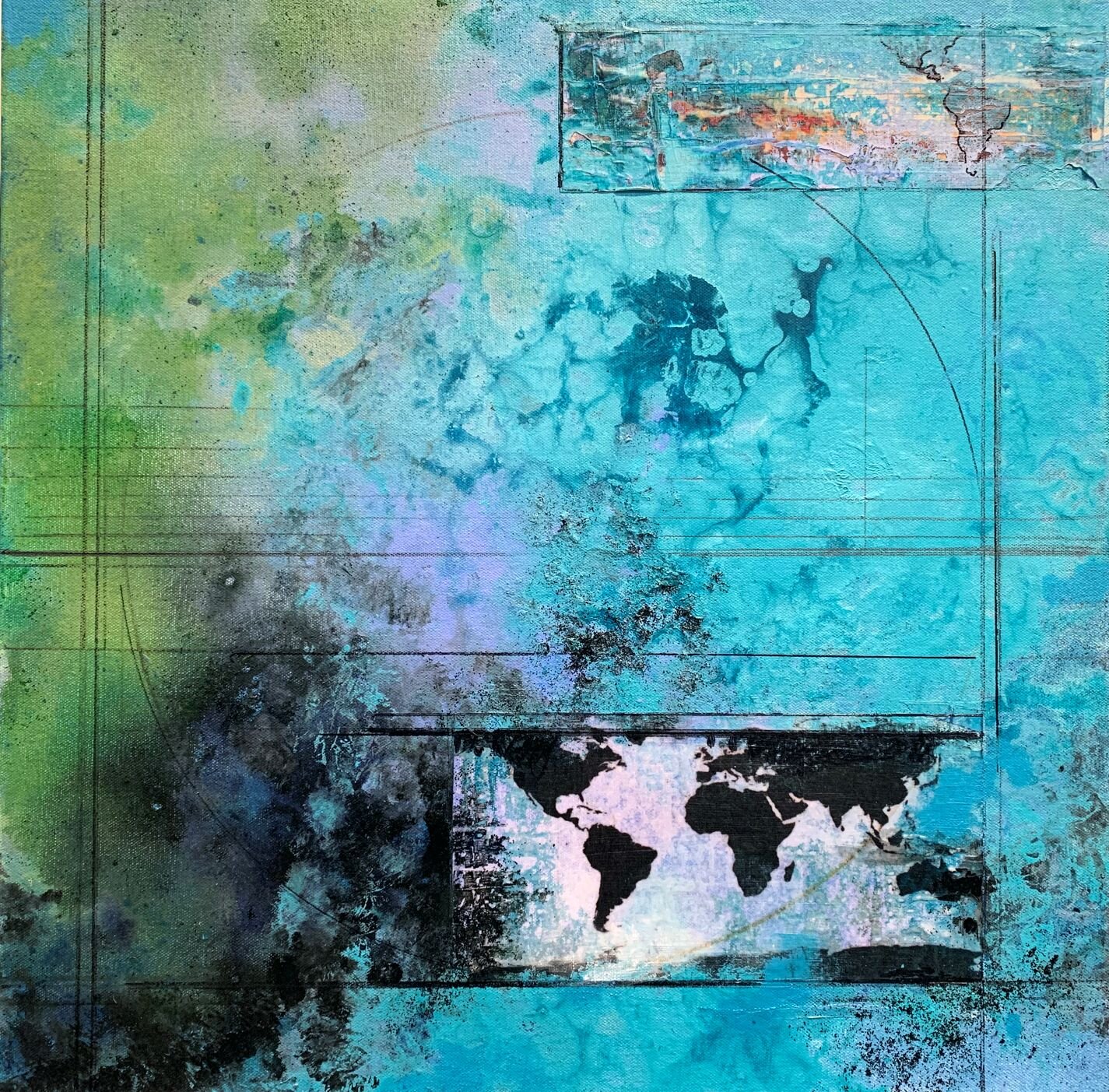

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Earth Day in April, Laura Igoe, the Michener Museum’s curator of American Art, and her team gathered artists from the greater Philadelphia region to produce Rising Tides: Contemporary Art and the Ecology of Water, an exhibit designed to highlight the interconnectedness of water and humanity.

When Igoe searched for artists to feature in Rising Tides, she decided that a local connection was necessary.

“I wanted to make sure someone was looking at what was happening locally,” Igoe says. “I think that brings deep issues home for our visitors from the greater Philadelphia region, and it makes these issues more tangible and something they can connect with their daily lives.”

Though Earth Day will be long gone once museums’ doors open again—the Michener Museum is closed until further notice due to COVID-19—the celebration of the planet, and this exhibit, will continue to resonate.

“Water is fundamental to life,” says Igoe. “It’s everywhere. I think in a lot of ways we tend to overlook or not think too hard about it.”

Marguerita Hagan inspects a coral reef-inspired sculpture| Photo courtesy of Marguerita Hagan

Featured artist Marguerita Hagan believes the pandemic emphasizes that now is the optimal time to take action in the climate crisis.

“It’s really time to wake up and work together,” she says. “The virus outbreak really hit hard after all these plans. But, it’s also driving home the absolute necessity of us changing our systems and how we interact and how we work together.”

The Rising Tides exhibit prioritizes ecological storytelling through the lens of seven local artists. It brings attention to the reality that as sea levels rise and global warming continues its course, we’ll be confronted with the fact that water can be both our savior and our destroyer.

“What I found as I started talking to people in the community … is that many artists that were concerned with the environment are specifically looking at water and water themes,” Igoe says.

The storytellers of the exhibition are all women—tying in the centennial of women’s suffrage. Being able to connect meaningful works of art with milestones such as this adds to the impact of the exhibit, Igoe says.

“I love that it’s an all-female show. There’s seven women in the show. And I just thought it was a beautiful, perfect way to be honoring Mother Earth,” Hagan says.

Hagan’s sculptures capture the complexity and beauty of the microorganisms of our oceans. Though they can’t be seen by the naked eye, organisms such as Radiolaria and dinoflagellates form “exquisite colony networks and systems,” she added.

Her delicate ceramic pieces, like “Daughter Cells” and “Frustule Flower,” give context and enlighten visitors on Earth’s primary producers. Combining a love for art and a love for the world that surrounds us is fulfilling, Hagan says.

“It’s really rewarding to be in a playground like this, to be sharing with other artists that are passionate about this, too,” she says.

Hagan, along with other featured artists such as Stacy Levy and Emily Brown, use their art to inspire. Whether it be an installation detailing the worrisome ebb and flow of flooding in Philadelphia’s Delaware River or charcoal sketches of a watersource’s surface, there is a call for change.

“Art connects people. Both the artists and the viewer can recognize their own experiences through a work of art and understand that they’re connected to other people,” says Brown. “It’s a sense of sharing a value or sharing an experience or a fear or feeling that bonds us.”

Brown’s aquatic drawings on paper highlight the transience of water and its infinite presence. “I have loved water for a long time as a subject because it’s something that’s always changing while it stays the same, kind of like a fire in a fireplace,” Brown says.

She also has ethereal pieces on display, like “Water Surface, Quiet” and masterful painted glass in “Underwater.”

Levy spent her childhood admiring the trees of Fairmount Park and the winding waters of the Wissahickon. Being neighbors with a natural forest was a big deal, and hours of adventuring were logged right in Levy’s backyard.

The “natural” and “urban” forests of Philadelphia, as Levy calls them, stuck with her while in college. They were her saving grace at Yale University. She was fed up with drawing, and she couldn’t escape the “tyranny of art history,” she says.

“There was an incredibly narrow definition of what art was … I was tired of arms and legs. I wanted something else,” Levy recalls. When she began to experiment with landscapes, rivers and forestry on paper, she found her passion.

“When I realized I could depict subjects other than bodies and food on the table, it was really a thrill to me,” she says. And the thrill wasn’t just from branching out in drawing topics. The rise of installation work and land art was an inspiration to Levy; eventually, it became her life’s work.

“Flood River (The Slower Tide)” is a massive installation featured in Rising Tides. With about 1,000 glass bottles swirling around the hall’s hardwood floor, visitors will see a powerful rendition of a section of the Delaware River.

Levy’s installation represents the inhale and exhale of the river, and how flooding can upend its natural state.

As it swells from an overabundance of rain, bottles that were once empty will be soon full; the viewer will see the impact of an overwhelming rain—a rain that isn’t so natural.

“When we think about climate change, the first thing we think of is the sea level rising,” Levy says. “But there’s another kind of tide thriving out there. And that is the changing regime of rain.”

In the past, cities like Philadelphia had a nice balance of rain, Levy explains. But with climate change, this balance has gone off-kilter. Philadelphia recorded approximately 61 inches of rain in 2018, just three inches shy of the level recorded in 2011, a year hammered by Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

As the atmosphere’s temperature rises, water evaporates in larger quantities, allowing for more precipitation, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. With more rain comes more flooding, which can damage watershed ecosystems that aren’t prepared for a rise in water levels.

Levy’s installation visualizes the chaos and inconsistency of the flooding of the Delaware. Some days, the bottles will remain untouched. Other days, volunteers may fill and empty them consistently.

“Flooding is guaranteed at some point. When it floods, you’ll actually be able to see how far the river will spread beyond the regular level,” Igoe explains. “Some bottles won’t be full until it floods. It’ll be an installation that’ll change for visitors over time.”

Seeing the vulnerable state of the river through art can influence a visitor much more than hearing about it through conversation. Levy conceptualized “Flood River” as a way to speak to people through a means that’s easy to understand. Science can be hard to decipher, even for ecologists.

“I believe that science has closed a lot of people out of understanding it, because it speaks its own language,” Levy says. She equates science with law: you have to be trained in that language in order to calculate the outcome.

“Art has a really strong role as a translator of ecology,” she says.

The piece at the Michener is one of many installations under Levy’s artistic belt. In the past, Levy constructed sculptures, walkways and gardens across the country to connect nature with visual experience. In 2018, she partnered with Mural Arts Philadelphia to create a floating installation at Bartram’s Garden that visualized the Schuylkill River’s cyclical tides.

Earlier this year, Levy installed “ Collected Watershed” at Towson University’s Center for the Arts Gallery. Similar to her work at the Michener, this installation used 8,500 glass jars and 1,000 gallons of stream water to re-create an interactive map of Towson’s watershed.

Over the years, Levy has constructed pieces that embody Earth’s natural flow—things like wind, rain, growth and decay, and even rising tides. At first glance, these themes seem disconnected from our everyday lives, but Levy argues that’s not the case.

“Some of my work is about making what people find invisible visible,” she says. “They can say, ‘Oh, wait, nature is happening here, too. It’s happening in the air in my apartment, it’s happening in my backyard, it’s happening in both the suburbs and the city.’ It’s important to feel a sense of connectivity with nature by knowing that it exists everywhere.”

Rising Tides aims to break down the barriers between the living: humans and the environment. We can easily forget about the aquatic world around us, Igoe and Levy argue we need constant reminders. “Artists can help visualize the abstract idea of global warming in a very profound way by providing new perspectives on our local and global environment,” Igoe says. “It brings climate change’s effects on water to the forefront of people’s minds.”

“Water is going to touch you in every aspect of what you do in your life. I don’t think we think about it that way. I don’t think we see how interconnected we are,” Levy says.

Witnessing the clear skies, the clean air and the drop in carbon emissions due to social distancing and stay-at-home orders is inspiring. But it raises the question: What will happen when things return to “normal?”

Will we forget the lessons of the pandemic, or will we finally understand the worth of water before the well runs dry and the floods arrive?

Updates for the opening day of Rising Tides: Contemporary Art and the Ecology of Water can be found at www.michenerartmuseum.org.