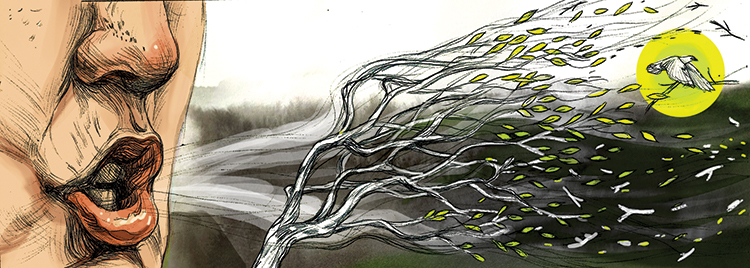

Illustration by James Olstein

Victory or Defeat?

by Jerry Silberman

Question: How much can I grow in my garden?

The Right Question: Do urban gardens have a place in a sustainable food production system?

Food provides both all the materials we need to build our bodies and all the energy to run it. Any animal (or society) that uses more energy on a daily basis than it consumes in food soon starves to death. Access to fossil fuel energy has allowed human society to produce food at a huge energy deficit.

This fossil fuel subsidy has also allowed a growing percentage of our burgeoning population to have nothing to do with growing food: Within the last few years, for the first time in history, the majority of people live in cities.

In past generations, urban and suburban backyard gardens were much more common than they are now. Even with the return in popularity of community gardens, and the appearance of a few urban farms, Philadelphia grew more of what it ate in home gardens in the ’50s, and in every decade before that, than it does now.

During World War II, having a “victory garden” was a patriotic duty, and up to 40 percent of our vegetables were homegrown. Community and home gardening were boosted by the influx of African- Americans from the South in the early ’50s, and declined as that generation passed.

Home gardens had begun to decline before the war under the pressure of the growing food industry. The beginning of refrigerated transport of vegetables helped discourage gardening. Through the middle of the 20th century, often the only way to get those really fresh tasty vegetables—even in season—was to grow them yourself.

Today, some of Philadelphia’s Asian and other immigrant communities are among the most energetic gardeners, because some of the vegetables central to their food culture aren’t easily available in our grocergy stores.

In many community gardens, the benefit of activating the community, the safety benefits from reclaiming vacant lots and the contribution to food security is probably greater than the net energy gain from local garden plots: That’s a murkier picture.

Vegetables grown in pots, with highly amended soils, watered from a tap, started from the seeds of plants grown hundreds of miles away and shipped in glossy paper envelopes most likely use far more energy than they will provide the eater. That’s especially true if they are low energy density foods such as lettuce, greens, herbs, peppers, etc.

If your garden is in actual soil, and your soil is being regenerated by organic, on-site practices, and you are growing fruit and nut trees, or higher energy but less glamorous veggies such as potatoes, beans or beets, you might actually be getting a net energy surplus, especially if you are saving your seed.

Some vegetables will never produce an energy surplus—but they are worth it because they provide important vitamins and minerals. They can be grown without an energy surplus when we understand them as part of a complete system of food production that operates with a net surplus of energy for us and for our land.

The foods that we depend on for the bulk of our calories and nutrients are meat and grains, including nongrass seeds like buckwheat, nuts and legumes. With the exception perhaps of a backyard chicken—or a yard-filling fruit or nut tree—these don’t do well on a backyard garden scale.

But the most important role for a backyard garden may not be what it produces for you, but what it teaches you about food production. What can you learn from the work that it takes to maintain your garden and the reliability of production? From the life of the soil in which your plants grow and changes in that soil as the years pass? What do you observe about the ecology of weeds and small animals, or even the people in your neighborhood? Even the most casual gardener cannot help but to learn lessons about water, temperature and changing seasons, as well as see on a micro level what large-scale food producers know: There is a trade-off to growing specialized plants that produce more but are more vulnerable to environmental challenges, and pesticides are an easy out (like using that can of bug spray to try to save one head of cabbage from the caterpillars).

One of the biggest lessons most urban gardeners will learn is that they still need the supermarket, and gardening can teach us respect for the farmer, who needs to reliably feed not only her own family, but the rest of us. It’s an ever greater feat if she is committed to doing so sustainably—that is, without the external inputs of huge fossil fuel subsidies in mechanized agriculture, fertilizer and long distance transportation.

How far and how fast our fossil-fuel-subsidized food supply will drop—and with it, global population—is anyone’s guess. What’s not a guess is that re-creating sustainable food production systems will be a steep learning curve for populations that have been away from the land for generations. Present urban gardens may or may not be part of the solution.

Out of necessity, our food systems will transition toward sustainable systems. The role of our gardens will increase, but their role will always be complementary to the role of farms that are—hopefully—within visiting distance of our own urban plots.

Jerry Silberman is a cranky environmentalist and union negotiator who likes to ask the right question and is no stranger to compromise.