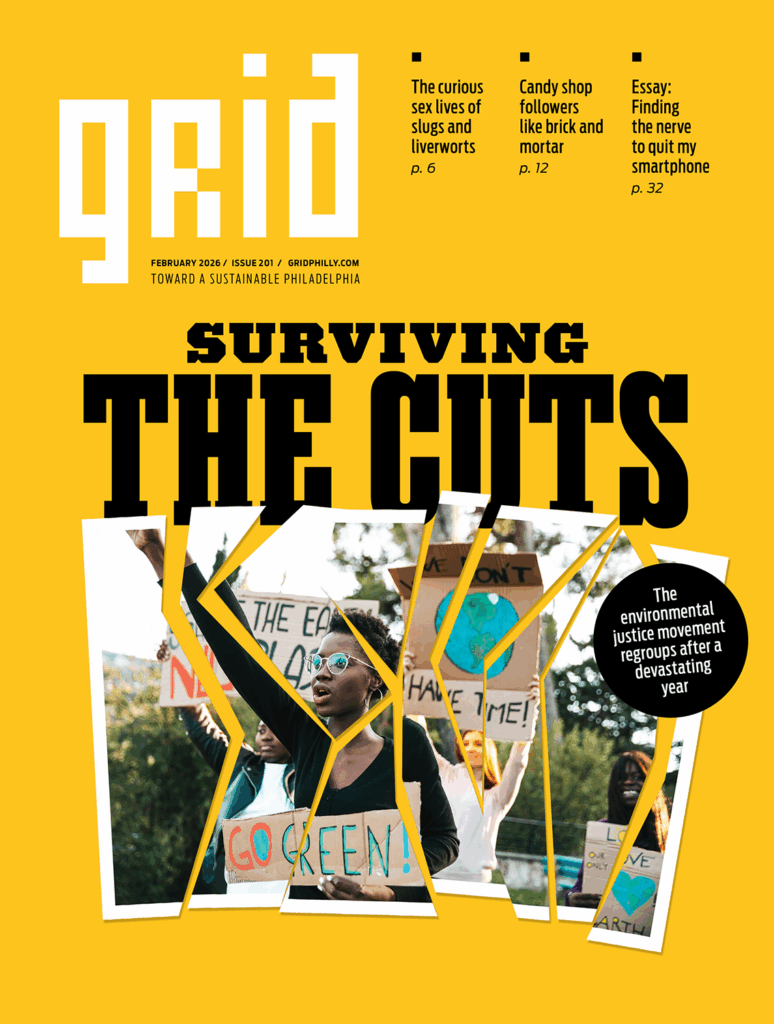

Kids taking a hike with the Urban Blazers program learn which berries are edible | photo by Urban Blazers

by Hannah Waters

The woods of Fairmount Park are haunted. There, in a dilapidated hut, lives the Green Lady, according to local legend. She roams the park with a single purpose: to steal kids who venture too far into the forest and, in some tellings, eat them.

Folklore often hides a kernel of truth, and the lesson of this Philadelphia legend is clear: Stay out of the woods. However, in July, four campers with Urban Blazers plainly exhibited a different attitude towards the Green Lady as they hiked down Boxers’ Trail, a 3.8-mile path that winds through Fairmount Park from Strawberry Mansion. They pointed out a hut across the stream—the Green Lady’s house—and, in their spookiest voices, foretold that she would steal us away. But Janae Squire, 11, was having none of it. “She’s not real,” she assured me with an eyeroll.

Squire’s attitude—her sureness of self and her comfort in the woods—exemplifies the work of Urban Blazers, a Philadelphia nonprofit founded in 2005 that immerses kids from under-resourced neighborhoods in their local parks. Many poorer neighborhoods have beautiful parks nearby, “but they are not being accessed by the people who live in those neighborhoods,” says Eric Dolaway, executive director of Urban Blazers. “The access issue is less about physically being able to get to a trail, and more about knowledge and confidence.”

Instilling that knowledge and confidence requires supplanting a fear of parks that is justifiable given their recent history. The Green Lady kept kids safe when Philadelphia’s parks filled up with trash and crime in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s. The last decade has seen investment and improvement in the parks, but cultural attitudes take longer to catch up.

Urban Blazers is rigorously structured to create a new culture of fun and enjoyment around parks, and it’s reached nearly 7,000 kids since inception. In addition to a suite of summer camps, staff and volunteers meet with the same classes in partnering charter and independent schools every single week, leading the students in team-building games and developing mentoring relationships. The games focus on building trust among the students, and feedback sessions after each visit let them voice their joys and frustrations. The approach builds camaraderie in the classrooms so that students feel safe with one another even when feeling unsafe in the woods and parks.

There are additional benefits. “Plenty of teachers give us the feedback that their kids communicate better and that there’s less bullying in the classrooms,” says Dolaway.

The team-building activities prepare students for monthly ventures into the woods (taking public transit whenever possible) for a walk and unstructured play. Unlike many environmental education programs, Urban Blazers doesn’t explicitly teach science and nature. Nonetheless, it offers access to rich ecological knowledge. During one trip, campers foraged for mustard seeds and wineberries. They pointed out poison ivy along the trail’s edge, and then a natural remedy growing nearby: jewelweed, which spills a pain-relieving juice when you break its stem.

More than local ecology, this knowledge lets them have a safe and fun time in the woods, especially if they return alone. Dolaway knows that the kids are going to try berries, so he teaches them which ones are safe to eat and which are not. They’ll climb trees regardless, so he teaches them to recognize when a tree-climbing situation veers into dangerous territory.

That knowledge brings them comfort, as what once scared them becomes familiar. “I thought it was going to be scary and boring,” says Amir Barbee, 12, about his first time in the woods. “But then we came out here and it was so much fun!”

It’s the fun that makes the difference in building a long-term love of parks. Many schools bring students into the woods only for science class or trash pick-ups. However, “unstructured experiences in nature are just as important, if not more important, than structured experiences for developing a connection to the environment,” says Marianne Krasny, Professor and Director of the Civic Ecology Lab at Cornell University. “They’re more likely to result in an interest in the environment as an adult.”

While it’s a nice side effect, Urban Blazers isn’t looking to create environmentally conscious adults. It wants to see kids and teenagers using the parks today—and it’s working.

“After they go hiking with us, our kids go hiking again,” says Dolaway. “And they introduce their friends and their siblings and their parents to the trails we go hiking on. That’s something that we do that I don’t think is being done by anyone else.”