West Philly’s Hybrid X Team builds green cars, and the case for vocational education

West Philly’s Hybrid X Team builds green cars, and the case for vocational education

by Lee Stabert

OK, Disney movie pitch: A group of high school kids (almost all African-American) from West Philadelphia build cars for an international competition, striving for a $10 million dollar prize. There’s a handsome, ambitious teacher, highly-funded, flashy competitors with big names (and budgets) and an environmental angle—these vehicles are designed to get over 100 miles per gallon.

That’s a great story, one that’s familiar and easy to tell. But it might not be quite as interesting—or as important—as the messier narrative of how our society readies kids for a challenging future. If Philadelphia truly hopes to become the “most sustainable city in America,” creative, project-driven vocational education needs a place in the plan.

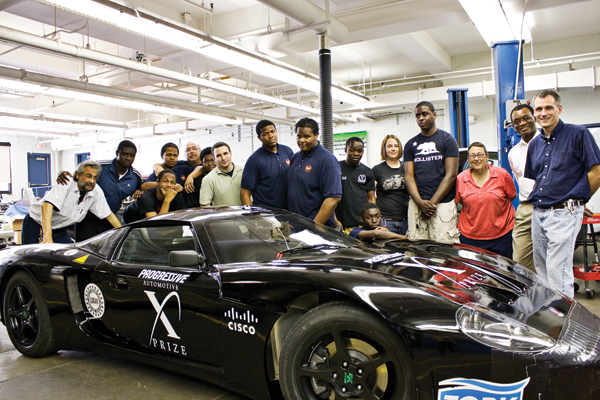

That movie matinee tale—lovable underdogs, hard-earned success, colorful characters—does apply to West Philly’s Hybrid X Team, an afterschool program at the Auto Academy focused on building electric and hybrid cars. They’re currently participating in the Progressive Insurance Automotive X Prize (PIAXP) competition, an international contest that challenges teams to design, build and sell super-efficient, consumer-friendly cars. Prize money totals $10 million.

The team has two cars in the hunt—a modified Ford Focus (bought for a good price from Pacifico Ford, a local dealership) and a GT, assembled from parts by the students and teachers. Both cars utilize plug-in hybrid technology and get over 100 mpg. The Focus features 81 batteries (in nine neat rows) and a modified motorcycle engine donated by Harley Davidson. The two-door GT has a Volkswagen diesel engine to augment an electric motor, and can go from zero to 60 in under five seconds.

From the original 43 teams, only 22 remain. Big names like MIT and Tesla were eliminated during the “Shake Down” phase of tests and benchmarks. West Philly Hybrid X, the only high school team in the competition, is one of only two teams with cars in both the four-door and two-door divisions. This month, they’ll travel to Detroit for “Knock Outs,” another series of cuts and evaluations, including rigorous technical inspections, on-track events and emissions and mileage testing.

“We have moments where we feel like we’re in way over our heads,” admits team director and founder Simon Hauger. “But then it dawns on me that everyone is taking us seriously. At the end of the day, we’re educators, and the fact that we’ve created this educational experience for our kids and they’re being put on a national stage, that’s really what we wanted. So, in many ways, I feel like we’ve won already.”

Hauger, a Drexel electrical engineering grad turned science and math teacher, launched the team 10 years ago. “At 24 years old, I thought everyone should go to college,” says Hauger. “I was placed in the Automotive Academy and I was quite disappointed that I was working with vo-tec [vocational tech] kids. I thought I should be working with the college-bound kids. But I quickly realized that people learn in different ways—some of the smartest people I’ve ever worked with were shop teachers.”

As Hauger’s outlook shifted, he began to look for new ways to engage the teachers and the students. That’s when he created the afterschool program. Not originally designed with an environmental focus, the team encountered its muse in the form of an electric go-cart. “PECO was sponsoring an electric go-cart competition, and they donated one, so we had it in the shop,” recalls Hauger. “I challenged the kids to turn it into a science fair project, and they did exceptionally well. Kids from West Philly hadn’t done well in science fairs previous to that, so we wanted to do something bigger. The next logical step was an electric car.”

Hauger has a low-key energy about him that belies an intense focus. His blog posts on the team’s website are casual yet detailed. He also has a sly sense of humor, referring to one round of “Shake Down” tests in the X Prize competition as “a bad proctology exam.” And the success he’s had with the team is simply astounding—they’ve won the Tour de Sol, an annual showcase for environmentally-friendly vehicles, three times.

Hauger has had plenty of help. Team Manager Ann Cohen—who wrote about her disco-era passive house in May’s Grid—spent most of her career working as a union rep for the city. In the early ’90s, there was a dispute regarding contracts for rebuilding engines and transmissions. “One day, one of the managers in the police department called me up,” explains Cohen. “He said, ‘Hey, would you mind if I sent some engines over to Edison High School to have them rebuilt?’ After I got done cursing him out—and filing a grievance—I called him back and said, ‘If you really want kids to get experience, then we’re doing a real internship program.’” In 1993, the city and the union launched a joint internship and apprentice program for the city’s automotive academies, moving students from high school into full-time jobs maintaining the city’s fleet. The program continues to this day.

“I worked with all the programs in the city,” says Cohen. “West stood out. They were producing the best kids, and I became a fan of Simon’s work.” Cohen started dragging her family to watch the Hybrid X Team compete, and eventually became involved with fundraising. “When it was time to retire, they had a wonderful position for me: full-time volunteer,” she quips.

Ron Preiss and Gerry DiLossi, both former full-time mechanics, are teachers at Auto who devote tremendous time and resources to Hybrid X. They speak both personally and passionately about the impact vocational education can have on students.

“This has been my thing from when I was a young boy,” says DiLossi. “My father had a garage up the street. Eleven years old, and I could walk three blocks and play mechanic.” The South Philly native was a school district employee for seven years, repairing buses and cars, before he became a teacher. In 1980, he started working towards his college degree, and graduated from Temple in ’98—his oldest son beating him to the cap and gown.

Last year, DiLossi was recruited by Preiss to join the team at Auto. “The year before last, I was the only auto teacher here and I was getting my butt kicked,” explains Preiss, also a Philadelphia native who grew up in the far Northeast. His dad was a scientist, and he too grew up playing with motors and machines. “When I came out of high school, I knew where I was going,” he says. “Fixing cars was all I wanted to do.” After 17 years running a garage, he was hired by the school district. He’s also working towards a degree in education.

Both men talk persuasively about the varied nature of talent and intelligence. If you can show the value of a lesson, kids will get excited. “I ran an auto shop, and I had people work for me who could not read, could not write their own name,” says Preiss. “There was at time when that was OK. But now, you need to be able to write descriptively and explain yourself well so you can get paid. A guy might write down, ‘RR Alternator,’ but he never wrote down the fact that it took him two hours to find the problem. So, he didn’t get paid for those two hours. Descriptive writing—being able to write down everything you did on that service order—is what puts money in your pocket. Some kids who are graduating from high school can’t do that.”

DiLossi argues that project-based education can provide a dynamic learning experience. “Learning how to read manuals, that’s important,” he says. “In the auto field, you need science—hydraulics is important. And they learn the chemistry of biodiesel. And math, they have to know fractions; they have to know metric. And you have to know angles for alignment. It’s important to know these things.”

Hauger agrees. “From an educational standpoint, we try to frame out a problem with the kids,” he says. “There’s just so much rich learning to be done in a project like this. And I don’t want to underestimate the amount of knowledge we’ve accumulated over the last 10 years. We’re not automotive engineers, but we’re also not just a bunch of teachers who are doing it for the first time. If you look at the cars we built the first year, and the cars we’re building now, there’s a huge difference. We’ve really taken the X Prize rules very seriously—we’re building cars that consumers will want.”

Then, of course, there are the students. After a chat with the grown-ups, Cohen and Hauger pass me along to three of their team members for a tour. These young men are no strangers to press interviews—their composure and kindness signal a maturity that doesn’t often come to teens before they’ve worked really hard on something they care about.

Daniel Moore, a 17-year-old junior, helped out last year, but has been an integral member of the team since October. “I got interested because I like cars,” he says. “And I like being on a team that actually built a car that’s running.” Moore enjoys drawing, as well as building things, so he’s thinking about a career as an architect. When asked how the team celebrates their achievements, he gives a typically understated answer: “We always have the pride and joy over it, but we don’t want to celebrate too much. We want to win the X Prize.”

Not all team members work on the cars—all talents are welcome. Some students design marketing plans, while others work on the website or collaborate on speeches for presentations.

Justin Clarke, a 19-year-old junior with a deep voice and lilting accent, was born in Trinidad & Tobago. He had been struggling in school, but then, this fall, DiLossi pulled him aside, told him he had potential and suggested he join the team. After a chat with Hauger, he was on—as long as he pulled up those grades. He did, and, with visible pride, Clarke tells me about a recent letter he wrote to Mayor Nutter, thanking him for visiting the team’s workshop. The Mayor wrote him back, thanking him.

Many of the students talked about the grade requirements as a motivator. If you don’t have the grades, you can’t be on the team, so they get the grades. The teachers even coordinate tutoring for team members.

When asked what kind of car they would drive if they could have any in the world, Michael Glover, also a junior, points at the their GT—the gas-electric hybrid in a sports car’s body—and says matter-of-factly, “I would drive this one. I wouldn’t have to pay for any gas.” Glover, who also plays football, loves working on cars. Like his teammates, he has embraced Hybrid X’s unheralded status: “We’re the underdogs,” he says. “We’re the only high school. People that don’t know much about us think we won’t do much.”

The success of the team—and that Disney-ready storyline—has led to a plethora of press coverage, most recently the cover of Brass Magazine. “My mom was bringing it to church showing it to everybody,” says Glover with a smile. “Other people talk about their kids to my mom, and she always says, ‘Michael, when you gonna make me proud?’ I guess me coming here makes her proud.”

So, at its root, this story is about forward-thinking education—which just happens to look a bit like old-fashioned education: learn a trade, develop a skill set, and get a steady job in the rapidly-evolving economy. With concrete goals—like the X Prize—the advantages of learning become tangible, something worth working towards. “When you have 50 percent of the kids in Philadelphia dropping out of school, it’s horrific,” says Hauger. “The emotional drain that takes on us is tremendous. There’s no reason that should be happening. When you engage kids’ creativity and curiosity to solve real problems—it doesn’t have to be electric cars; it could be designing green roofs or emission-free water heaters or cleaning up the waterways—the learning is real. We’ve learned a lot about what good education looks like.”

So, can they win?

“Miracles are possible,” says Hauger. “It would be kinda like your high school team beating the Philadelphia Eagles. When Aptera pulls up with their $550 million dollar setup and 70 engineers, it’s fun to fantasize that we could beat them. But the fun thing about car competitions is that we’ve routinely beat cars that are better funded than ours. We fully expect to go there and be incredibly competitive, and everybody is treating us that way.”

If they pull it off, someone better get Disney on the phone.

For more on West Philly Hybrid X, visit evxteam.org

I found the perfect place for my needs. Contains wonderful and useful messages.

These kids are an incredible inspiration and a source of pride for me. This team just impressed me so much.

Damn. That was good. It looks like the Ford GT. Awesome men..

The attainment of the side—and that Disney-ready storyline—has led to a plethora of depress coverage, most recently the enfold of Brass Magazine. “My mom was bringing it to church presentation it to everyone,

As I came to know about this after school program of cars I am really happy that such type of classes have started. We are now-a-days very much concern about the electric and hybrid cars as per the pollution of environment is the major issues. So such type of after school programs in auto academy will provide sufficient and useful information to the car mechanics to make such electric and hybrid cars. So, that by using these cars we can minimize the pollution level of our environment that caused due to ignition process of the vehicles engine.