When my editor asked if I’d like to write a foraging article, I said I’d think about it.

I have avoided writing about foraging for a while now. Foraging—looking for wild plants and fungi to consume—seems to be growing as a hobby, and it’s an obvious topic for a nature writer. But it has always struck me as a little crass.

The natural world has its own value. I want to get beyond considering a plant, an animal, a mushroom or anything else as interesting only to the extent that it fills a material human need. Wildlife is worthy of our attention on its own terms, not just ours.

The irony here is that as much as foraging can bug me, I’ve been doing it for years.

On a counter in the kitchen, not far from where I write at the dining room table, sits a tall glass jar full of a brown, murky liquid. At the bottom rest a couple dozen immature black walnuts that I picked back in June from a tree in my in-laws’ suburban yard. Every few years I make nocino, a bittersweet liqueur that hails from northern Italy, by steeping the walnuts in grain alcohol.

In the freezer I’ve still got some pesto I made this spring from garlic mustard, an invasive weed I yanked out of the woods at the end of a birding walk. For dinner last week we had a bean stew flavored with epazote, a Mexican herb that grows from sidewalk cracks around my neighborhood in West Philadelphia.

And that’s just what made it home.

When I’m in the garden I munch on the lamb’s quarters, dandelion and purslane as I weed. On hikes I keep an eye out for the fruit of the season, snacking on serviceberries, mulberries, wineberries or chokecherries. Throughout the year I Iook out for wild persimmon trees with their scaly, deeply fissured bark. Their fruit is at its best in the winter.

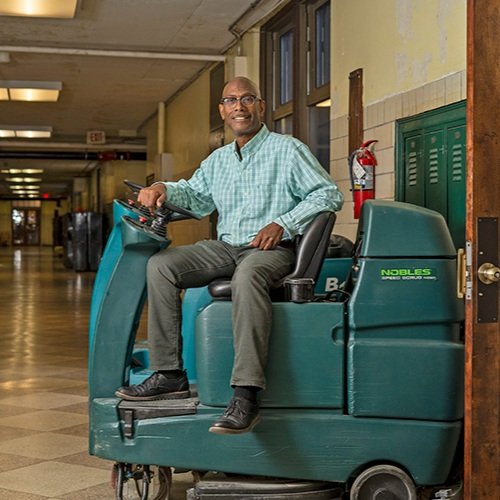

I was still dragging my feet on this article when local naturalist Ed Edge pitched a series of foraging topics for Grid’s #GreenFriday video series, including late-season targets like pawpaws, black walnuts and mushrooms. Edge, who splits his time between Philadelphia and Costa Rica, where he helps run a wildlife clinic, enjoys birding, tracking mammals and otherwise observing wildlife. He eats what he finds where he finds it.

“I spend an asinine amount of time frolicking in the bush,” he says. “I’m notorious for carrying two things: a machete and a fanny pack. Because of the lack of gear and supplies, eating the plants surrounding me became an essential activity for lasting 12 hours outside.”

Edge showed up to our first video shoot with a ripe pawpaw. Pawpaw is the fruit of a native tree related to the tropical custard apple. They get up to the size of a mango and are shaped like a kidney. Inside they have a creamy, pale yellow flesh with large black seeds, and they taste like a cross between a banana and a mango.

Pawpaws are hard to find locally, though more trees are getting planted, as native fruit enthusiasts and land managers realize how yummy they are. (Their leaves also host the caterpillars of a spectacular butterfly, the zebra swallowtail.) Edge told me that a local patch was fruiting, and I made a point of going the following Saturday, dragging my sharp-eyed nine-year-old daughter with me. Together we gave a few trees a gentle shake and collected the handful of soft, ripe fruit that fell.

Soon after I emailed my editor to say that yes, I would write about foraging.

Of course, there is no rule that we can’t value the natural world on its own terms and consume some of what it produces. Indeed foraging, as well as hunting, is the original way we humans fed ourselves, obtained medicines and sourced building materials.

As Edge says, “Few things bring me more joy in life than being outside in the elements and eating the plants that surround me. It reminds me of how I’m supposed to act as a Homo sapiens.”

To keep it sustainable, it’s important to observe some basic guidelines:

-

Whatever you harvest, leave some for your fellow foragers, human and nonhuman.

-

Following on Rule #1, stick to foraging methods that preserve the source. Avoid digging up roots or taking whole plants, unless it’s an exotic weed you’d be removing anyhow, like a burdock or a garlic mustard.

-

Know what you’re eating before you put it in your mouth. There are a lot of plants and mushrooms that can make you ill, and a few that can outright kill you. Go on plant and mushroom walks with experts, use virtual tools like the iNaturalist app to help with identification, and get some guidebooks that cover your target species. When in doubt, don’t eat it.

-

Follow rules of parks and other local spaces. With so many people using so little park space, local land managers have to be careful about what they allow. Keep an eye on park programs for foraging walks and other opportunities to sample wild fare in a sustainable way.