There had to be a better way to build a park, thought Kimberlee Douglas, director of Landscape Architecture at Thomas Jefferson University.

Through her work at Jefferson, she did a lot of community outreach. She would hear from people in underserved communities that they wanted parks, but they had no easy way of getting them built.

Working with the city was time consuming, expensive and often frustrating. One park, or near-park, still makes Douglas incensed.

“Six years ago, [Mayor Nutter] hosted a ribbon cutting party for a park that was to be built on the corner of Cecil Street and Kingsessing Avenue. They have the money for it, but the city will not sign off on the five-year lease.”

Douglas doesn’t remember exactly when the concept for Park in A Truck was born, but it’s an idea that Fast Company described as “IKEA, but for building neighborhood parks.” The magazine was so enamored with the idea it was a finalist in the Social Good category in its 2020 Innovation by Design Awards.

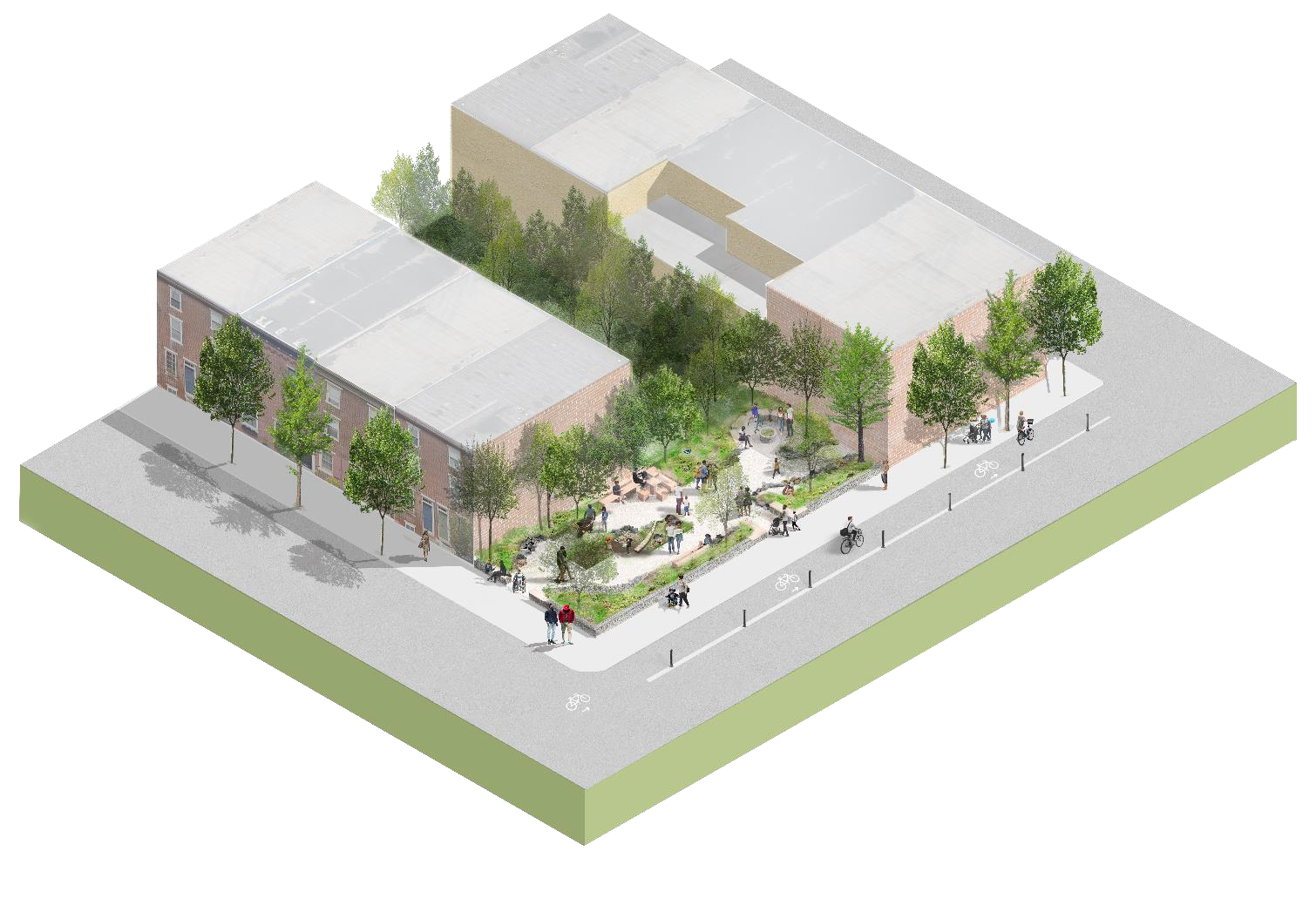

Park in a Truck, developed by Douglas and population health professor Drew Harris, was conceived to prove that if parks could be designed modularly, and avoided pouring cement as well as the city’s bureaucracy, they could be executed quickly and with community input.

With the help of her students, Douglas came up with four different types of park: sanctuary, event space, edible and nature.

“But they are all like puzzle pieces, so they’re interchangeable. So you could have a sanctuary edge, an interior edible, and maybe there’s an event space that’s geared towards nature,” says Douglas.

She took her idea to the Mantua Civic Association, where she was greeted with indifference and suspicion.

“They did not know me. They did not trust me, and I don’t blame them,” Douglas says.

But she was persistent. She kept showing up, knocking on doors, trying to make connections. “And I guess they started to believe [me] because I just didn’t go away,” Douglas says.

Not only did they come to accept the idea, the community galvanized and rallied to support it. A location, at 38th and Melon streets, began to take shape.

Douglas says construction of the parks take between 6 and 8 weeks, relying upon volunteer labor for four- or five-hour shifts on Saturday mornings. The 38th and Melon location is, by Douglas’ estimate, two-thirds of the way finished as they await the completion of a building across the street. Like everything else, it has been delayed by the pandemic.

A key lesson that Douglas imparts to her students is that design isn’t solely an academic pursuit. It’s necessary to engage communities.

“It’s not just a design program. In fact, I think … design is sort of secondary sometimes.

“I really want [students] to learn how to run a community meeting or how to … do an agenda or, you know, how do you talk to communities. They present to the planning commission, or to Curtis Jones’ council people, they meet them. It’s really integrated, and they’re really immersed in the issues of the day.

“So it’s not just learning how to be a designer, it’s learning how to be a designer with a conscience based in good ecology and social understanding.”

Currently, a second park is being built in West Kensington, and Douglas is developing online tools that would allow people to design parks themselves.

“I’d be happy if I never saw a park be built again because [communities] were doing it [themselves]. I mean we’re happy to lend our expertise. But I want it to be initiated by the community. And for it to be their choices, not mine. We see ourselves as facilitators. We’re facilitating this process.”

The mission of Jefferson’s College of Architecture and the Built Environment is to educate the next generation of design and construction professionals to create an equitable and sustainable future. Learn more at Jefferson.edu/Grid.