The ultimate vision of an eco-friendly and educational urban oasis

The ultimate vision of an eco-friendly and educational urban oasis

by Natalie Hope McDonald

The sounds along Lancaster Ave. in West Philadelphia’s Overbrook neighborhood don’t usually include chirping. But on one overcast day in May, across the street from the U-Haul rental center and footsteps from a fruit and vegetable bodega, a small red-breasted bird whistled over the rattle and hum of traffic on this, one of the city’s long-forgotten corridors.

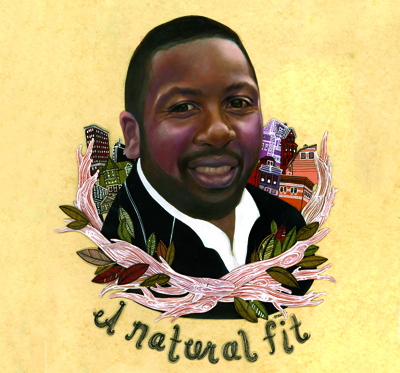

“That’s not a pigeon,” says Jerome Shabazz, the mastermind behind the Overbrook Environmental Educational Center (OEEC), a nonprofit at 61st and Lancaster. “Birds will make the site a part of their annual migration,” continues the youthful-looking Shabazz, a former Philadelphia Water Department worker with a vision. He plans on attracting an array of native species to the site that both he and his wife Gloria started building several years ago. “They stop over when they see trees and a green space,” he says, admitting that it’s unusual to find any natural habitat in the run-down concrete jungle around Lancaster, which began carrying travelers as early as 1795.

Surprisingly situated between abandoned factories, burned-out rowhomes and boarded-up nightclubs, a grassy lot is just starting to bloom. Young Japanese maple trees, dew-covered spring flowers and a quarter-acre of thick woods create a backdrop to this future hub for eco-friendly education and better living.

A building supply company in recent years, and a granite quarry dating back to the 1800s, the center is truly Shabazz’s baby. He’s spent the better part of two years preparing for the day when neighbors will be able to learn about green energy, take healthy cooking classes, study natural ecosystems in outdoor labs and experience the benefits of reusable rainwater in the city.

It wasn’t easy convincing anyone the good that an environmental education center would bring to a post-industrial urban environment. But Shabazz, along with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and a very hands-on board of directors, has removed potentially toxic waste from the site, making room for a series of eco-friendly additions to the property.

It’s been a long road, but this year you can see considerable progress in greening the space. “Philadelphia Building Supply left behind old cars and containers filled with mystery fluids,” says Shabazz, “as well as debris and pre-treated wood with arsenic.” His recent—and revealing—500-page report for the EPA details the site’s progress, goals and ongoing maintenance, making it a safe educational destination in a uniquely urban environment. “Most other centers like this are in the country or the suburbs, but here, people in the city will be able to come together and learn valuable skills.”

The 45,000 square-foot site, which hosts an art center, a conference and training center (to be housed in two separate buildings that are being remodeled using eco-friendly building materials), and a wooded area with outdoor classrooms, will be completed next year as much-needed donations trickle in from private, corporate and government grants. Even though construction is ongoing, programs are already being offered this year in the 4,500 square-foot art center, which includes a coffee shop, bakery, working kitchen, dance studio, art gallery, office, small stage and event space.

“We’re hosting a summer camp for the first time this year,” says Roosevelt Sanders, one of OEEC’s board members. He says the day camp was inspired by many years of working with local elementary and high schools on eco-friendly programs in Overbrook. Shabazz’s work teaching school-age children about the environment is what inspired him and his wife to create the OEEC. At the time, the couple’s own son was enrolled in public school, facing all the same limitations when it came to the cost of providing effective science programs.

The Ripple Effect

“My son talked about studying ecology at Overbrook High School,” says Shabazz, who was especially curious about a subject close to his own heart: environmental science. “I asked him what he’s gone out and seen. And he told me they hadn’t seen anything.” Instead, the science program consisted of textbook-bound learning, which inspired the father to ask himself how his son and fellow students could learn hands-on about the world within their own community. And how he would convince the schools to think outside the classroom.

Shabazz worked with Vivian Robinson, the director of Overbrook High School at the time, to create a program that would allow kids to study the impact of pollution on their own park and water supply. They would learn about science, the elements and chemistry through real-life experiments and fieldwork. He credits Robinson, now deceased, with having the faith to see the idea through. More than five years later, the curriculum is still being used and the Center is a reality.

For the first project, students adopted Indian Creek in nearby Morris Park at 66th and Sherwood. “We removed weeds and cleaned up the stream and stream bed,” says Shabazz. “And we discussed point-source pollution.” The students also learned how to test water, a nod to Shabazz’s own experience with the city’s water department, and the importance of keeping the environment clean. The lessons would be shared with each student’s family, creating an eco-friendly wave of learning in a community that suffers from all the usual issues of urban blight: crime, violence, poverty and pollution.

Within two years of creating this educational program with the Overbrook schools, Robinson tracked a noticeable increase in the participating students’ overall grade point averages. “The students were visual learners,” says Shabazz. They learned by creating their own recycling programs for paper, plastic, aluminum and glass at home and at school; and by using outdoor biolabs to learn about stormwater management, urban conservation and eco-friendly landscaping at the Center, even though it was just getting started.

Since beginning the community-education partnership, science teachers have joined with math and English instructors to implement environmental studies as a multidisciplinary classroom discourse. “English teachers have children write journals about how their environment changes,” says Shabazz. Math teachers work with students to calculate rain flow on a green vegetative roof compared to a traditional, non-vegetative roof.

The program also teaches students about Overbrook’s own history as a one-time center for farming, an upscale suburb to downtown Philadelphia and an important railroad hub. The students learn about industrialization and its impact on the air, water and local food supply, as well as distinguishing freshwater from wastewater (with a visit to the Philadelphia Wastewater Treatment Plant) and tracing the source for their home and school’s water supply.

Suddenly, kids who equated science with textbooks too heavy to carry home in their backpacks were using terms like flocculation and sedimentation, and taking an active interest in their community. “The beauty in the Center is that it’s in an ultra-urban environment,” says Sanders. “People in the community can walk to it and be able to identify something positive in the neighborhood. We all want to be a part of something historic in terms of having an environmental center in the middle of Lancaster Avenue.”

Summer School

The Center is using the successful education program as inspiration for OEEC’s first-ever summer camp, starting in July at the art center. Children from first to eighth grades are invited to participate in day and weeklong programs headed by Teenagers in Charge’s Judith Dumorney-McDaniel, a member of OEEC’s advisory board. High school-age students will also have the chance to log community service hours by assisting at the eight-week summer camp to learn leadership skills.

“We’ll focus on health, fitness and fun,” says Dumorney-McDaniel. Each program will incorporate exercise into the daily routine. Children will also have the opportunity to run their own T-shirt and poster printing business, and take field trips within the community. Dumorney-McDaniel will take the children on trips to farmers’ markets to teach them the importance of eating fruits and vegetables. There will also be cooking demonstrations for the entire family, including vegan menus, to emphasize better dietary habits.

“If we can help these young people to change their behavior of going to fast food restaurants to showing them how to make their own meals, they’ll see the value and that they taste good with only a few minutes of work,” she insists. “We’ll also share that information with their parents. We want to eventually be able to offer programs to entire families.” OEEC will begin hosting personal enrichment programs, or a “CommuterVersity,” for adults in the evenings on everything from healthy cooking to wellness and computer skills.

Sanders says that while the new summer camp is designed for kids, the Center wants to involve entire families and initiate conversations between parent and child, even if it means something as simple as going to the coffee shop together for a fresh-baked organic snack, or participating in an art show.

“Last year, we did a photo contest with Overbrook Elementary called ‘Faces and Places of Overbrook,’ ” says Sanders. Children were asked to take photos from their community, school and home. The best photos spent a year on exhibition in City Hall, and participants received prizes from Best Buy, a sponsor of the contest.

“It was really surprising,” he says, explaining that kids with no photo training went out in the community and took creative pictures of neighborhood buildings, the postman on their street or the neighbor’s dog. “As a young person, I was taught to see the greater value in art and music. These things make children more interested in school.”

The Power of Green

Despite the ongoing success of these enriching community programs, Shabazz knew that he needed help making the actual Center a reality. A mere two years ago, he stood on a property consisting of two former storefronts and an empty lot, wondering how to transform them into the Center he and his wife dreamed about.

As Shabazz faced his biggest challenge, he read an article about urban greening and development by architect Todd Woodward, principal of SMP Architects in Philadelphia. Woodward is also a member of the Community Design Collaborative, a volunteer organization of design professionals that assist nonprofits with community-minded projects. Shabazz would tap into both resources to start the blueprints rolling—literally.

“I started working with Jerome pro bono in 2005,” says Woodward from his office at 16th and Walnut. “We identified the work on the site in phases.” The goal is to use green materials to rehab existing buildings for the Center.

For starters, certified lumber from sustainable forests was used to create roof decking on the center, which will be turned into a vegetative roof that harnesses rainwater for the plant life on the site. “We feel that from an environmental point of view, it’s better to reuse and recycle rather than build new,” says Woodward, who claims both structures are in good working shape, making the job considerably more advantageous. It’s also cheaper to reuse some of the existing materials than to pay a third party to dispose of them in landfills, an option Sha

bazz wanted to avoid.

Other design elements include a bio-retention basin for harvesting rainwater runoff, flow-through planters and an urban garden with native plants. Leftover stone dividers, used by the building supply company to store lumber, will be turned into outdoor classrooms. “The hope,” says Woodward, “is they can become individual garden plots where students can do experiments and create different soil conditions.”

The OEEC will also build a hoop farm, a raised-bed greenhouse, with the help of Penn State University. The greenhouse will be used to grow plants and food in a controlled environment, something that will be a first for Overbrook.

“Hopefully it will be a little bit of a catalyst on Lancaster Avenue,” says Woodward, who explains that many of the Center’s features can be used to educate other community members, homeowners and businesses about eco-friendly building. “The green roof will lessen the heat gain, so that it makes it easier to cool the building in the summer. It also diverts and holds storm water. The one we’re installing will be on the long face of the building with a sloping roof that is visible from the ground.”

Woodward and Shabazz both hope the Center inspires the community to consider green technology, including solar power. At the conference and meeting center, which will eventually consist of two floors of classrooms, labs and meeting space, students will be trained in green technology and building (from installing solar panels and building green roofs to learning weatherization techniques to save money on heating and cooling costs). “People can eventually be trained to install these products,” says Sanders, who admits the vision is enormous but necessary to create interest and jobs.

Shabazz enthusiastically leads a tour around the Center, jumping from the art gallery to the coffee shop, offering samples of fresh vegetables and pointing out the new trees he planted this year with the help of almost 90 percent minority-led contractors. He’s particularly proud of the porous asphalt and mulching system that eliminates ponding. “There are five different ways to capture water here,” he says, pointing out the swell and flow-through technologies hidden beneath emerald green rain-soaked grass.

Shabazz eventually climbs atop a small mountain of enormous granite rocks that borders a thick quarter-acre of woods behind the Center. “When you stand here, it’s hard to believe you’re in the city,” he says. He points to a knotted vine and jokes about Tarzan, picking up a rock mined more than 200 years ago. Like most every other natural material, it, too, will be somehow reused on the site.

“You can always find value if you know where to look for it,” he muses. Shabazz just happened to look where no one else thought to.