Illustrations by Kathleen White

Illustrations by Kathleen White

Is a proposed petrochemical hub a devil’s bargain? The CEO Council for Growth says it is an opportunity for economic revitalization, while organized opposition throughout the city says it will drag us into our past. Must we choose between prosperity and pollution?

Philadelphia’s role as a vibrant manufacturing center faded decades ago, bringing both hardship and benefits. The loss of companies that employed hundreds of thousands of people was an economic blow, but also allowed the city to literally breathe a sigh of relief. Following a century of intense pollution, the shift away from heavy industry—as well as reduced use of coal, conservation, and technological improvements—contributed to a nearly 70 percent drop in toxic emissions in fewer than 20 years, from 1966 to 1985. Pollution levels have continued to fall since then.

Yet the major improvements of the last 50 years now face an unprecedented challenge. The chief executive of the city’s biggest polluter, the sprawling oil refinery along the Schuylkill River responsible for 72 percent of the city’s toxic air emissions, is touting a plan to significantly expand the use of fossil fuels in the heart of the city.

In the short term, the plant’s owner, Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES), has talked about increasing the number of trains that deliver volatile North Dakota oil through residential neighborhoods for processing into gasoline and other fuels at the PES Philadelphia Refining Complex. In the long term, CEO Phil Rinaldi aspires to build a 120-mile-long, 42-inch-wide pipeline from northeastern Pennsylvania, where hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, of Marcellus Shale deposits is producing huge volumes of natural gas. That gas would power factories and serve as feedstock for chemical plants, reindustrializing swaths of the city.

Forces are marshalling for and against the plan. The business community, Philadelphia City Council members and local congressmen are aligning themselves with Rinaldi, while groups like Clean Water Action, the Clean Air Council, Delaware Riverkeeper Network and the local chapter of the Sierra Club are working to publicize the plan’s potential hazards. What happens next will depend on a cornucopia of unknowns: energy and construction prices, the political leanings of a new mayor and new governor, big-industry muscle and residents’ willingness to fight for a future Philadelphia that isn’t haunted by the city’s industrial past.

“The city’s made great strides in improving air quality and water quality—however, that’s mainly because the manufacturing went away,” says Dr. Pouné Saberi, a board member with Physicians for Social Responsibility who spoke at a rally against the pipeline in December. “So, we got better because of the very things that polluted it, and now we’re trying to add that back?”

While conducting a burn-off on Jan. 10, 2015, a crude oil pipeline at the Philadelphia Energy Solutions Philadelphia Refining Complex in South Philadelphia caught fire, sending huge plumes of smoke over the city, according to city officials. There were no evacuations or injuries. | Photo by Tom Kelly IV

While conducting a burn-off on Jan. 10, 2015, a crude oil pipeline at the Philadelphia Energy Solutions Philadelphia Refining Complex in South Philadelphia caught fire, sending huge plumes of smoke over the city, according to city officials. There were no evacuations or injuries. | Photo by Tom Kelly IV

Back to the Future

Advocates of natural gas argue that it helps ease environmental burdens because it burns cleaner than coal and oil (although pollution figures often don’t factor in the environmental costs of extracting gas). Regulation-driven technological advances also help limit emissions. But each additional gas-fueled cogeneration or manufacturing plant will still add some combination of carbon dioxide, sulfur oxides, nitrous oxides, fine particulate matter and other pollutants to the air inhaled by Philadelphians.

New pollution would come on top of already heavy emissions. While our skies are clearer than they were a half-century ago, our children are still reaching for inhalers at alarming rates: Philadelphia is the fifth most challenging city for people with asthma, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. The city ranks 11th worst nationally for the ozone that makes up smog, and 16th for particle pollution or soot.

“In many cases, what we’re talking about is a difference in degree, not a difference in kind,” says Sam Bernhardt, a Food & Water Watch organizer in Philadelphia. The consumer rights group focuses on corporate and government accountability relating to food, water and fishing. “What we’re talking about is more pollution; it’s more dirty infrastructure; it’s more dangerous oil trains; it’s more other kinds of explosive and dangerous fossil fuels like liquefied natural gas; it’s more pipelines; it’s more manufacturing.”

Many city residents are only distantly aware of such hazards, Bernhardt says—at least for now. “But they are things that, if those pushing this ‘energy hub’ idea get their way, many more Philadelphians will be dealing with on a day-to-day basis” he says. “And those who are already dealing with these issues, those frontline communities, will be even more impacted by them.”

Opponents have additional concerns. The methane that makes up natural gas is extremely flammable, and has a potent greenhouse impact with a much more intense short-term global-warming effect than CO2. While newer pipelines are relatively safe, the older gas pipes under Philadelphia’s streets are rife with leaks and occasionally explode, with deadly results. For some experts, that legacy raises concerns about how our children and grandchildren will be affected by current projects.

“All of the pipelines that we are building will be old one day,” says Dr. Marilyn Howarth of the Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology at the University of Pennsylvania. “If attention is not paid to how they are maintained, and if there aren’t regulations in place that clarify the expectations that they be maintained and not leak, what we set up is a situation that could be very dangerous for many communities.”

There are also environmental and safety impacts from cutting a pipeline channel through forests and under neighborhoods. And, back in Northeast Pennsylvania where the gas is extracted, a host of concerns about water pollution, soil compaction and waste disposal remain.

Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, says she’s also aghast at the prospect of the pipeline being buried in the Delaware River, an option Rinaldi has mentioned. She called it an “outrageously harebrained concept” that could, in the case of an accident, prove catastrophic for the 17 million people who depend on the river for clean water.

“They’re looking at the river as if it’s a delivery pathway or a ditch—it’s not,” she says. “The river’s alive, and it supplies people with something they cannot live without. There would just be an environmental backlash like never before should they try to put a huge 42-inch pipeline down the bed of the Delaware River. We would fight it tooth and nail.”

Shrouded in Secrecy

Rinaldi, who declined to be interviewed for this article, became Pennsylvania Energy Solutions’ CEO when the company was created two and half years ago to save the South Philadelphia refinery from shutting down. With well-developed rail, highway and shipping infrastructure that connect the site to suppliers and customers, it has become a profitable maker of oil products. But for Rinaldi, a much richer future remains just out of reach.

“We don’t have that opportunity with natural gas,” he says in a promotional video produced by the CEO Council for Growth, an affiliate of the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce that is spearheading the pipeline project. “We have no choice but to take that dry gas, that methane, and get it into a pipeline from northeastern Pennsylvania down into the Philadelphia region for redistribution.”

Fracking has created a glut of cheap gas that producers are desperate to move to factories and urban areas. But to justify building a billion-dollar pipeline, Rinaldi first needs to convince many other fossil fuel-based industries to set up shop in the city. Those new plants would inevitably pollute the city’s skies and waterways.

The exact effects of the pipeline are tough to gauge because little information has been released. A conference held at Drexel University in December was closed to the public, though it prompted the protest rally attended by Saberi and more than a dozen groups opposed to the plan, including 350 Philadelphia, Berks Gas Truth, the Clean Air Council, Clean Water Action, Philadelphia Interfaith Power and Light, and the Sierra Club.

Security was tight: Maxime Damis, an environmental engineering student at Drexel who belongs to the campus’s fossil fuel divestment group, says police swarmed her when she entered the Creese Student Center, where the meeting was being held, and made her leave. “My plan was to sit there quietly, listen, and have a few targeted questions,” she says. “They didn’t have anyone asking those questions.”

In published interviews, Rinaldi has not discussed the specific health and environmental impacts of a new pipeline, though he has dismissed opposition to fossil fuels as unrealistic. Rep. Bob Brady (D-Pa.), who was instrumental in keeping the refinery open, did not respond to an email, and a spokeswoman for the Marcellus Shale Coalition did not return phone messages.

Even the route of the new line remains unclear. Rinaldi has only said that the “last 10 to 20 miles is going to run through Philadelphia, where it becomes much more expensive to site a pipeline.” Nor has he named companies that would buy the gas, though in an interview posted by the Chamber of Commerce, he says the firms could include oil refineries, steel makers and steel rolling operations, in addition to chemical companies that turn gas into methanol, ethanol, urea and ammonium nitrate.

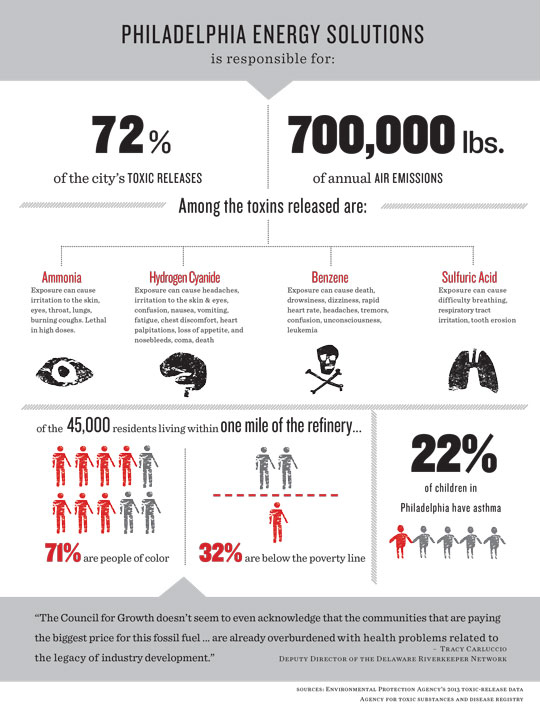

One fact we do know is that the city’s current air pollution already comes disproportionately from his company. According to one Environmental Protection Agency measure, Philadelphia Energy Solutions’ refinery already puts out 72 percent of the city’s toxic releases, including 700,000 pounds of annual air emissions. That includes sulfuric acid, which causes acid rain and can harm the lungs, along with hydrogen cyanide, ammonia and highly carcinogenic benzene.

As for greenhouse gases, the refinery emits 2.9 million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year, 5,900 tons of methane and 3,200 tons of nitrogen oxides. The nitrogen compounds contribute to Philadelphia’s high levels of ground-level ozone, which burns the lungs and increases vulnerability to respiratory and circulatory diseases. For 2014, the American Lung Association gave Philadelphia an F for air quality in part because it has 50 high ozone days a year—days when children, active adults and anyone with breathing difficulties should limit their outdoor exertion.

Philadelphia Fire Department responds with a hazardous materials dispatch, including at least one medic unit, to the Philadelphia Energy Solutions Philadelphia Refining Complex fire on Jan. 10, 2015 in South Philadelphia. | Photo by Tom Kelly IV

Philadelphia Fire Department responds with a hazardous materials dispatch, including at least one medic unit, to the Philadelphia Energy Solutions Philadelphia Refining Complex fire on Jan. 10, 2015 in South Philadelphia. | Photo by Tom Kelly IV

An Environmental Justice Nightmare

Those bad days, when levels of ozone and particulate matter are high, are especially stressful for parents of children with asthma.

“The way I tell parents to think about it is, ‘Take a deep breath, breathe it out, then take a deep breath and try to breathe that same air out through a straw.’ You can see a big difference,” says Dr. Tyra Bryant-Stephens, director of the Community Asthma Prevention Program at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “Inflammation causes swelling of the tissue inside, and causes increased mucus, and can cause constriction around the airways.”

All that makes the affected child’s airway smaller, leading to scary and potentially dangerous breathing problems, she says.

“If you already have a little inflammation, you already have a little mucus, and now you go outdoors and you have emissions of sulfur dioxide or other pollutants, you’re more likely to have symptoms like wheezing and coughing and difficulty breathing,” she adds.

According to Bryant-Stephens, who works primarily with black and Hispanic children in

West Philadelphia, irritants like sulfur and nitrous oxides not only make breathing more difficult for children whose lungs are already inflamed, but can also sensitize the airways in the first place so that they then react to allergens in the environment.

Sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides are also among the chemicals that turn into microscopic particulate matter. The particles lodge deep in the body, aggravating asthma, chronic bronchitis, coughing and breathing problems and heart disease—and causing premature deaths. Some 1,550 such deaths could be prevented in the Philadelphia metro area every year if air quality standards for particulates were tightened, according to a study by the American Lung Council, the Clean Air Task Force and Earthjustice, a nonprofit public interest law organization. Increased pollution, meanwhile, would lead to more early deaths.

Cheap gas could lure a variety of companies to the area, each with their own profile of toxic pollutants. Plastic manufacturers, for example, can release an alphabet soup of compounds, including carcinogens like vinyl chloride and ethylene oxide.

“The body doesn’t see particulate matter separately from nitrous oxide, separately from benzene, separately from sulfur dioxide. It sees it as air pollution. It sees it like a combination, a cocktail,” says Saberi of Physicians for Social Responsibility. “That’s why the vulnerable populations make a difference. If you’re already an asthmatic, it makes a big difference. If you already have heart disease, it makes a big difference.”

A 2014 EPA study noted that of the 45,000 residents who live within a mile of the South Philadelphia refinery, 71 percent are people of color and 32 percent are below the poverty line, two groups that are already at high risk for respiratory and circulatory disease. A survey that Bryant-Stephens conducted in similar neighborhoods in West and North Philadelphia found that 22 percent of children had asthma, well above the national figure of 10 percent.

“The Council for Growth doesn’t seem to even acknowledge that the communities that are paying the biggest price for this fossil fuel, this dirty energy development that they’re promoting, are communities that are already overburdened with health problems related to the legacy of industry development over the last century and a half,” says Carluccio, of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network.

A Pipeline to Nowhere?

The glut of fracking gas has created huge economic incentives to build pipelines from the Marcellus region to urban areas, swaying public officials to go along with such proposals. Political leaders like Gov. Tom Wolf, Brady, and Rep. Patrick Meehan (R-Pa.), support fracking and related industries, as do many Pennsylvanians. Lines are spreading everywhere; in 2013, even New York City got its first new gas pipeline in 40 years, despite concerns about health risks from fracking that eventually led Gov. Andrew Cuomo to ban the technique statewide last December.

Fighting pipeline proposals is hard. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which approves pipelines, doesn’t even factor environmental issues or communities’ wishes into its decisions, and almost never turns down an application. While FERC

hearings do give citizens a venue to make public comments, pipeline opponents say that the commission often does not make a good-faith effort to let all voices be heard, holding too few hearings and locating them far from affected communities.

At the same time, those challenges don’t mean Rinaldi’s project is a sure thing, in part because of its unusual structure. To justify the new flow of gas, he’s depending on the establishment of new petrochemical industries within the city limits, which would need the support of local officials and the public. That gives opponents and concerned families a major opening to change the terms of a debate that has so far been largely framed by Rinaldi and the Chamber of Commerce.

“There’s a whole lot of steps that have to take place,” says Gretchen Dahlkemper, a Southwest Philadelphia resident and national field manager for Moms Clean Air Force, a group of parents united against air pollution. “The people of Philadelphia can get ahead of it and tell Rep. Brady, Rep. Meehan, Councilman Kenyatta Johnson and the mayoral candidates, ‘Hey, stop, we don’t want to be a hub of the petrochemical industry, we don’t want to be a hub of liquified natural gas exports, because of the numerous health and safety risks associated with that.’ ”

Through mayoral debates and council candidate forums this election season, as well as public forums on the pipeline that Dahlkemper’s group plans to hold, Philadelphians can create a climate inhospitable to more fossil fuel development, she says.

“If we get enough of the constituents to oppose it, they might rethink the decision,” she says, referring to pipeline proponents. “There might be a pipeline built—but they’re not going to build one if they don’t have anywhere to use it.”

—-

Want to get involved? Read author and activist Eileen Flanagan’s story on ways to make your activism count.

Thank you for this. Philadelphia Energy Solutions refuses to produce documentation of the air quality monitoring reports that they conducted after last Friday's fires. There is zero respect for residents' health and safety, and the city is doing absolutely nothing about it.

It seems rather disingenuous to not inform your readers that the vast majority of that 72% of "toxic releases" and 700,000 lbs of airborne emissions actually consists of CO2… the stuff every human on earth exhales when they breath.

Darling, no: http://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000336994

WHAT? CO2 is killing this planet. There's no reason our city should cater to the oil industry which wants to kill us making even more of it. Electric trains, lithium batteries, solar and wind. That's our future. PES is the past and it needs to go away.

okay what happens to children in the middle east and Africa where crude is being harvested?

yet you sit in your nice cars and go for long-drives in your AC running car without thinking about the other side.

think environmental, then justice.

its greedy!!!!

Thank you for running this most important story.

There is a coalition building against this petrochemical hub disaster, and once this idea is defeated, we need to go on the offensive and rid Philadelphia once and for all of this putrid-smelling, unhealthy, cancer-causing refinery.

Philadelphia Energy Solutions is a cynical, Orwellian euphemism for a company that doesn't give a damn about Philadelphians.

Here’s a link to a coalition of environmental and civic groups dedicated to fighting this polluting proposition:

http://greenjusticephilly.org

Sign up for the email list!!!