In June 2026, Philadelphia’s current solid waste and recycling contracts are set to end, and a coalition of policymakers, industry professionals and advocates hope to use the contract expiration as a lever to fundamentally shift the City’s waste management practices toward circular approaches that include reuse, recycling, repair and composting — while addressing environmental justice issues.

Critics say that the City of Philadelphia has prioritized disposal over alternative waste management strategies such as reuse, recycling and composting for decades. As the City’s first recycling coordinator, Maurice Sampson, likes to say, “The motto of the Sanitation Department is ‘throw trash and look good.’”

Since the pandemic, Philly’s recycling rate has hovered around 12%, refusing to budge even with Mayor Parker’s establishment of an Office of Clean and Green, which purports to exist to tackle the city’s pervasive litter issue and catapult Philly to the “safest, cleanest and greenest big city in the nation.” Advocates like Shari Hersh of Trash Academy question how Philadelphia can be the greenest big city while diverting 12% of its waste and sending 40% to be burned at an incinerator just down the river in Chester, Delaware County.

“If Philadelphia is serious about becoming the cleanest and greenest big city in America, we must end incineration and ultimately landfilling too, and ensure that our sanitation contracts include robust waste diversion requirements,” Hersh said at a City Council hearing in November.

Burn, Baby, Burn No More

Incineration has long been part of Philadelphia’s waste disposal portfolio, and under the Kenney administration, the City even considered it part of its 2017 strategy to achieve zero waste by 2035. It claimed that because burned trash was turned into energy at the Reworld (formerly Covanta) waste-to-energy facility in Chester, it counted toward the City’s zero-waste goal. Advocates allege that by burning its trash, whether for energy or not, the City of Philadelphia is perpetuating environmental racism in Chester while also contributing to health issues there and in surrounding cities like Philadelphia.

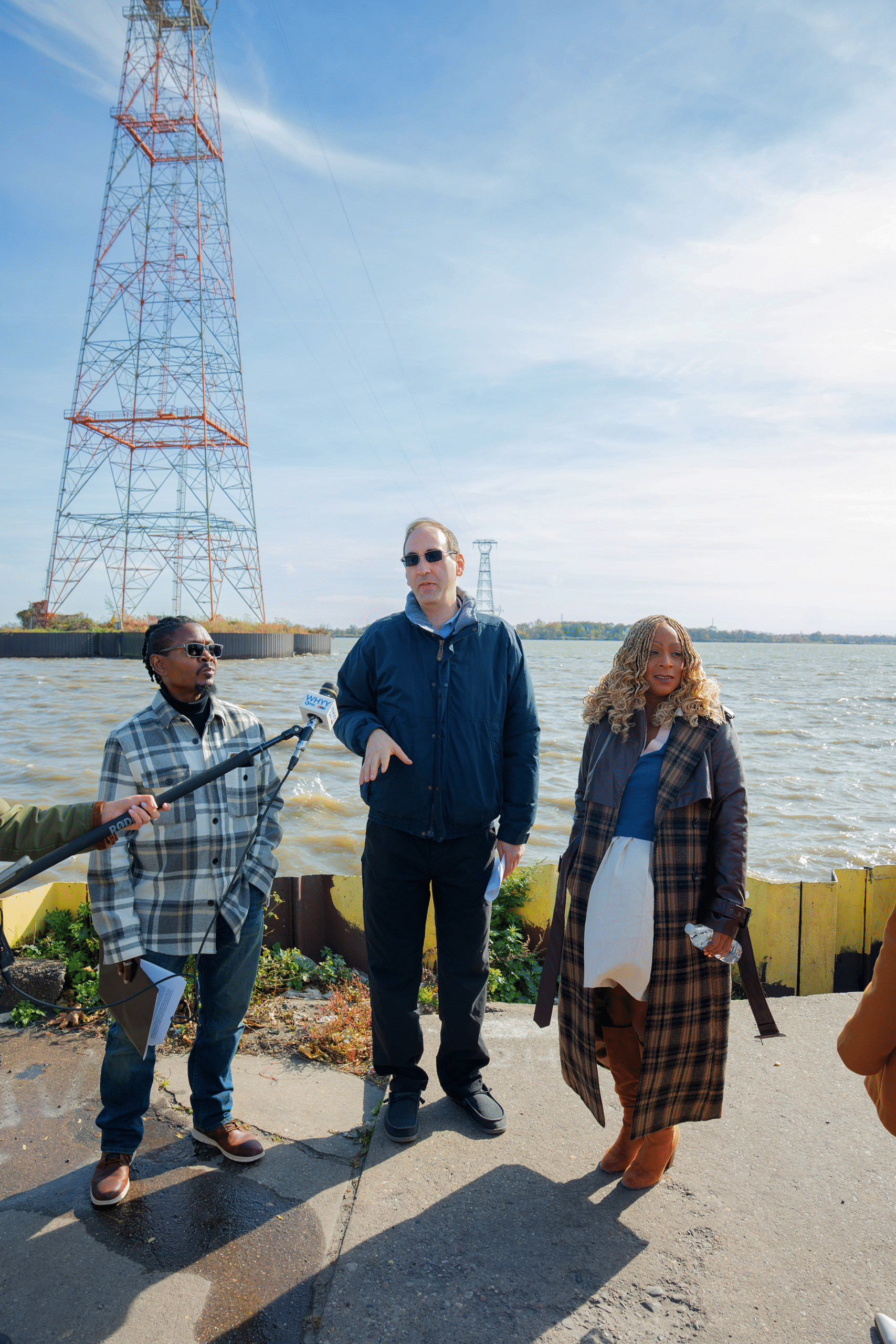

All of these issues caught the attention of Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, who took over as chair of City Council’s Committee on the Environment in 2024 and began convening advocates and environmental practitioners to hear their perspectives. “I wanted to ground myself in what the most current and pressing issues were for people,” says Gauthier. In both 2024 and 2025, ending the practice of incineration came up as a priority.

“It just doesn’t sit well with people that our city would be participating in environmental racism in Chester,” explains Gauthier. “For me, I took it on because my constituents also experience this kind of environmental racism. And as a city, we should be examining our waste practices and making them as sustainable as possible.”

With the solid waste contract ending in 2026, Gauthier decided that the time was right to introduce a bill that would fundamentally change how Philadelphia manages its waste. The Stop Trashing Our Air Act, introduced by Gauthier in September, would ban the City from incinerating any of its waste.

The bill has been met with mixed responses. Advocates from the Energy Justice Network, Delco Environmental Justice and Chester Residents Concerned with Quality Living (CRCQL) praised it, but the Parker administration has been conspicuously silent. Gauthier suspects that the administration isn’t thrilled about the bill. “They don’t like being told what to do about waste management,” she says.

Still, Gauthier points to some positive signs that the City may be willing to revisit its waste management practices. She was able to get Office of Clean and Green director Carlton Williams to say his office would take a look at this issue on record during the budget hearings in April. Her office also worked with a team at the Department of Sanitation and the Office of Sustainability to issue a request for information (RFI) to solicit ideas for how the City could incorporate environmental justice targets and circular waste management requirements into the request for proposal (RFP) that will be released for companies bidding on the City’s solid waste and recycling contracts.

“We’ve definitely had some good movement and conversation,” says Gauthier. “That was a good exercise to show how we should be thinking about waste management in Philly.”

Is It Too Late?

While Gauthier is hopeful, the City has put itself in the familiar position of being months away from contract expiration with no RFP in sight. Most recently, this happened in 2018 (as reported by Grid) when the recycling contracts expired with no new contract in place, and the city resorted to burning half of its recyclables.

According to one source — a Philly-area waste management professional with decades of industry experience and familiarity with how Philadelphia’s waste and recycling contracts work who requested anonymity to preserve business relationships — the absence of an RFP all but guarantees that the next contracts will simply maintain the status quo and be awarded to the current vendors. For recycling, that’s WM (formerly Waste Management), and for solid waste, that’s Reworld and WM.

For the recycling contract, there are two deterrents to potential bidders aside from WM.

First, the lead time before the new contract takes effect is too short for any company that doesn’t already operate a recycling facility in Philadelphia to open one by July 1, 2026. Second, the extremely short four- to seven-year recycling contract term (compared with 15 or 20 years in many peer cities) makes it so there’s no guarantee that the potential bidder will be able to recoup the cost of opening a new facility while still entering a competitive bid.

Williams underscored the latter point about contract length in his recent testimony at November’s City Council Committee on the Environment hearing on Gauthier’s bill. “Ultimately, the longer the term of the contract,” said Williams, “the more stable and the more valuable — lower — the rate is.”

The same waste management industry source says that if the City of Philadelphia truly wants to meet its sustainability goals, it must release an RFP that provides an environment for competitive bids from multiple companies. This includes, at minimum, a two-year lead time and a longer term agreement than the four to seven years that the City has typically offered.

Without this, it’s likely that WM will be the only bidder for Philadelphia’s recycling, meaning that WM will handle both the city’s recycling and solid waste. This puts the City in a precarious position because WM has shown in the past — most notably in 2018 — that it is willing to play hardball to extract higher fees from the City when it has no alternatives for its recycling.

Philadelphia’s waste and recycling contracts are the bottleneck preventing real change.”

— Candice Lawton, Circular Philadelphia

Without a competitive bidding process, the waste management industry source said, the City could be overpaying by tens of millions of dollars for the recycling contract alone.

And when the cost of recycling substantially exceeds that of landfilling, budget concerns routinely trump sustainability goals and recyclables get landfilled. As of September 2025, Philadelphia was paying WM $100 per ton to process its recyclables. When compared to the $70 per ton it pays to dispose of solid waste, it’s easy to see the disincentive for the City to recycle, especially when the recycling processor can just as easily landfill the materials under its solid waste contract with the City.

Similarly, the short bidding window for its solid waste contract will make it difficult for the Department of Sanitation to identify a cost-effective alternative to incineration. The Parker administration will likely use this as a reason why incineration must continue, even though critics say it will have been a problem entirely of the City’s own making, and that maintaining the status quo is baked into its contracting process. Until that changes, advocates say, there is little hope of more environmentally just or circular waste practices to replace the City’s disposal-first approach to waste management.

At the November City Council hearing, Hersh urged that “sanitation contracts should include composting to divert food waste, curbside textile collection, programs that recover construction and demolition materials.” She added, “It’s all being incinerated or landfilled.”

For people pushing for the City to prioritize sustainability, this makes Gauthier’s incineration ban bill all the more pressing. It’s one of the few levers that Council can pull to force the Parker administration to revisit its contracting practices. And if the City doesn’t revisit how it contracts waste and recycling this time around, it’ll essentially be another seven years before anyone has another chance at advancing environmental justice or circular solutions.

“Philadelphia’s waste and recycling contracts are the bottleneck preventing real change,” says Candice Lawton, executive director of Circular Philadelphia. “Everything we need — reducing waste at the source, expanding reuse and repair, building modern recycling infrastructure — requires innovative service providers offering circular solutions. Without contract reform, we stay trapped in an endless cycle of waste generation that ends in burying and burning valuable resources.”

What Happens Next?

When Grid contacted the Office of Clean and Green about Gauthier’s bill and the waste contracts, a City of Philadelphia representative issued the following response:

“The City of Philadelphia Municipal Solid Waste RFP for new waste management contracts will be published this fall. We are hoping that this RFP will encourage multiple waste reduction companies to offer solutions that provide environmentally sustainable and fiscally responsible proposals for the City to consider that meets the vision for a safer, cleaner, and greener Philadelphia.”

But the clock is ticking, and it’s not exactly the kind of response that inspires hope among advocates that things will change. They argue that if the City were serious about sustainability, environmental justice and fiscal responsibility, it could issue two RFPs at once — one for a short-term contract as a bridge that begins in 2026 and one for a longer term contract that begins in 2027 or 2028 with the option for potential vendors to bid on a 10-, 15- or 20-year term.

“This is more than a financial decision,” said Zulene Mayfield of CRCQL at the November City Council hearing. “It’s a health and a moral decision that needs to be made. Will you commit and continue to be complicit in environmental racism?”

The Committee on the Environment voted for Gauthier’s bill to pass out of committee at the November hearing. It now heads to the full City Council for consideration.

Gauthier is placing the ball in the Parker administration’s court. “Our values are not just defined by conversation but by action. Now it remains for them to do the right thing. They control procurement in the City of Philadelphia. There’s been some cautious partnership, but ultimately it remains to be seen whether they do the right thing.”

This special section is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This special section is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

The excuse “because red tape” (RFP procedures, etc.) doesn’t cut it. Who is responsible for for sending Philly’s trash to an incinerator? Trash incineration was never the right thing.