Camden

In June 2021, Grid published a story on flooding in Camden’s Cramer Hill neighborhood, highlighting the disaster’s disparate impact on low-income communities of color.

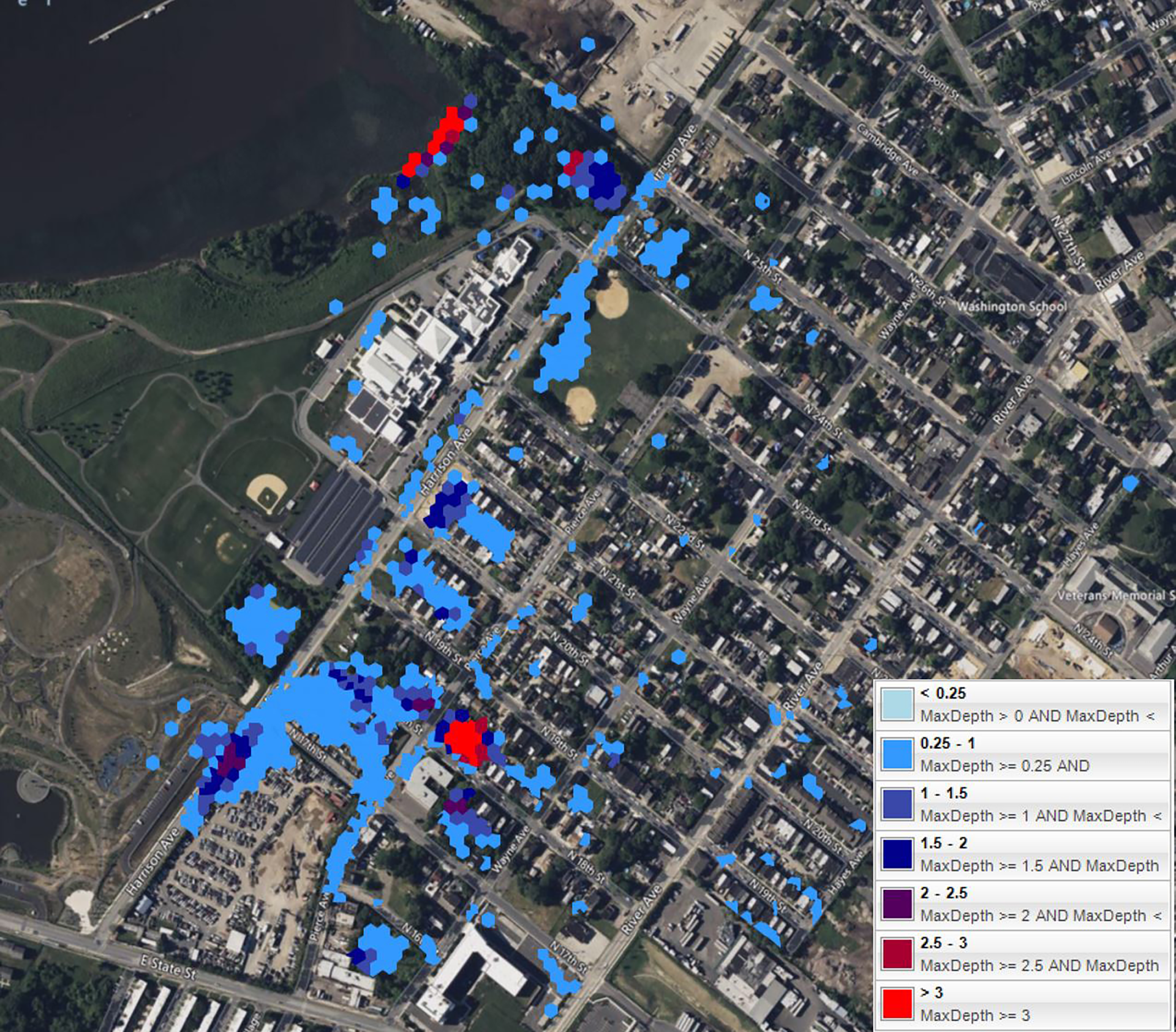

Since Grid last checked in, Franco Montalto, an engineering professor and researcher at Drexel University, and his team completed an advanced model that can simulate a variety of different infrastructure updates and climate scenarios in Cramer Hill. “It’s a lot like Minecraft,” says Scott Schreiber, the executive director of Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority (CCMUA). “The area is broken into very small blocks and each one gets a darker shade of blue depending on how much it floods in a situation.”

The team recommended that the CCMUA build a nearly 6-foot-tall drainage pipe under Harrison Street, one of the worst-flooded places in Cramer Hill. Smaller tributary pipes would bring water from surrounding streets to a main pipe that would dump the water into the river.

It won’t be cheap, but thanks to a $20 million grant from the Federal Emergency Management Authority (FEMA) and the New Jersey Office of Emergency Management, officials say Camden should be able to complete the project. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime investment, and so we would be foolish not to incorporate climate change,” Schreiber says. “We spent a lot of time really thoroughly understanding the problem, and then a lot of time designing it. We’re about to get into building it.”

The new system would be built to withstand what FEMA calls a 10-year storm, and will also include green infrastructure, bike lanes and pedestrian improvements — all of which officials say were requested by residents. They expect to start construction in early 2025, when they will also begin to address another problem: imported wastewater.

According to Schreiber, Pennsauken Township contributes to flooding and poor water quality in Camden by adding both wastewater and sewage to the City’s already-burdened system. Officials are planning a two-stage project to separate sewage and divert stormwater out of the city and into the Delaware River.

The neighborhood is also getting a facelift thanks to a $35 million Housing and Urban Development Choice Neighborhoods Implementation grant. The process began in February 2022 when officials broke ground on the new Ablett Village, which is estimated to cost about $145 million.

To qualify for a New Jersey flood hazard general permit, Michaels Organization senior vice president Nick Cangelosi says that the company builds at a foot over the floodplain level, which can mean elevating homes or, in the case of several of their Cramer Hill developments, adding extra layers of material to the ground itself.

“Everybody is evaluating climate change,” Cangelosi says. “The fact that water levels are rising, I think people are starting to get comfortable with it.”

You will never control nature, and therefore you work within it.”

— John Hunter, Manayunk Neighborhood Council

Venice Island

In September 2023, Grid reported on residential development on Manayunk’s Venice Island and the floods that washed over the island’s new apartment buildings and townhouses.

In September 2021, Hurricane Ida’s rain pushed the Schuylkill River’s waters into the first two stories of the Venice Island house shared by McKayla McLaughlin, her boyfriend Quinte Scott and their two-week-old son. In one night, they lost nearly everything — cars, furniture, professional equipment and countless personal items.

Because the family didn’t have flood insurance, nothing was covered. They moved into the South Philly house Scott grew up in, a fixer-upper that his grandfather left to him. “We had to start our whole life over again, just piece by piece putting it back together,” McLaughlin says.

Despite Pennsylvania laws requiring disclosure of a property’s flood history, McLaughlin says that she wasn’t informed that her home was in a flood zone, or how extensive past problems had been. She also reports that no one from property management or the ownership group contacted them to help the family to get back on their feet. JRK Property Holdings did not respond to Grid’s request for comment.

McLaughlin still wants answers.

“There just should be certain requirements,” McLaughlin says. “Why would you continue to have people move in, or why would you not make it so that if a flood did happen, it wouldn’t have such an effect on the tenants?”

One post-Ida change to the zoning code is a new requirement for buildings in the flood zone: mandatory pedestrian evacuation routes. The Isle Apartments is a four-story residential construction atop a parking area on the ground level that adheres to the new code. It has a pedestrian bridge to Main Street crossing the Manayunk Canal, which can be accessed at any time.

But even Main Street has been known to flood, raising questions about the efficacy of such a measure.

Some proposed developments, like the one at 3900 Main Street, rely on early warning systems to alert residents to a potential flood. The Schuylkill has a tendency to rise rapidly at night, causing additional concerns about residents’ awareness of danger approaching.

When Ida hit, “people went to bed and found their cars floating in the garage, or they couldn’t get out because the stairs were completely underwater,” says John Hunter, an architect and the zoning chair with the Manayunk Neighborhood Council.

Another building, at 4045 Main Street, which was once a family-run yarn-dyeing facility but closed after severe flooding from Ida, has an evacuation route on the back of the property which connects to Shurs Lane. But with updated floodplain estimates, it may be unsafe by 2050.

Hunter has a different vision for what Venice Island — and the rest of the neighborhood’s waterfront — could be.

He says he understands that developers and business owners want to continue building up Main Street in order to get a return on their investments, but also believes that there needs to be a long-term vision for the space.

“What we’ve been pushing the [Philadelphia City] Planning Commission to consider is what is now called a resiliency park,” Hunter says. The land is restored to a more natural state that’s better able to absorb flood waters and recover, reducing the overall impact of a given storm.

The park could also become a leisure space for hiking, biking and running, a concept that has been applied in other nearby states including New Jersey and Delaware. Building out that type of concept requires several things: mass purchasing of the lots by the City or another entity and a long-term plan for the space, for starters.

But Hunter says that the move is a necessary acknowledgement of the changes the land is going to go through, developments or not. “You will never control nature, and therefore you work within it.”

Eastwick

In January 2024, Grid covered the efforts to design a flood barrier for Southwest Philadelphia’s Eastwick neighborhood. At the time, the City had just presented designs by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at a community meeting.

On July 2, 2024, FEMA and the Biden administration announced that they would be providing $2.12 million in aid to install temporary barriers along Cobbs Creek, which is often responsible for the heavy flooding Eastwick residents experience. An additional $1.38 million had been secured through Congresswoman Mary Scanlon (D-PA, 5th District) to support the barriers and surrounding community engagement efforts by City government.

The barriers, which are made of wire mesh and large bags of sand, stand at about four feet tall. They have been used in the past to protect flood-prone and flood-affected areas, including reportedly holding back 1.5-foot storm surges in parts of New Orleans during hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

According to material from a town hall meeting in April 2024, the barriers will be stacked to create an eight-foot wall that will protect approximately 600 homes for between five and 10 years. But evacuations will still be necessary for large storms.

A more long-term solution to replace the barriers has hit a snag — one that has been steadily growing since October 2023. Despite releasing a draft study promoting a 1,400-foot-long levee, the Army Corps of Engineers has changed course after months of pushback from residents of both Eastwick and surrounding communities.

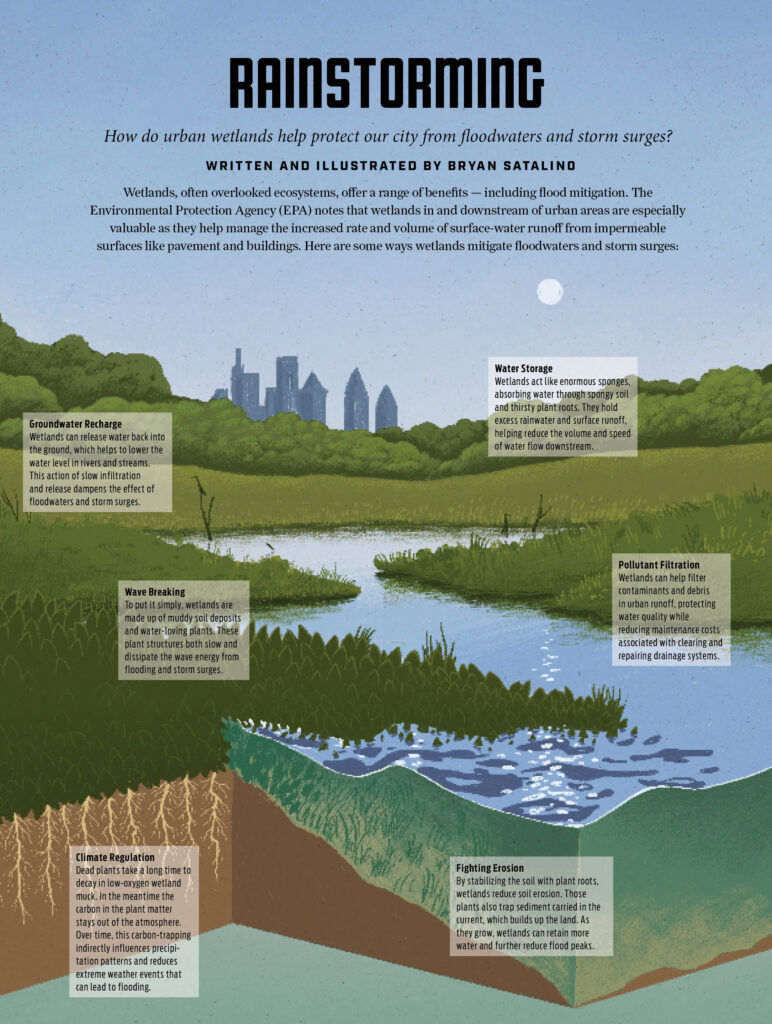

“That levee [model] resulted in 14 inches of induced flooding, which was unacceptable to everybody around the room,” says Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Beeman during a public meeting CBS Philadelphia reported on this summer. As a result, the team is going back to the drawing board, with proposals on floodwater storage and transfer options as well as wetland expansion.

The new report is set to be finalized in spring 2025.

Northwest Philadelphia

In April 2024, Grid reported on flooding in Northwest Philadelphia. While not much has physically changed since, new initiatives and leadership in water management have emerged.

Justin DiBerardinis is the new executive director of Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership, replacing Julie Slavet, who recently retired. With a background in environmental stewardship and education, including a decade of experience with Bartram’s Garden, DiBerardinis has a special focus on community engagement, particularly when it comes to the parts of water management that aren’t so easy to understand.

“It’s so important for communities to understand what’s going on, because we need public will to create the political will to change things for the better,” DiBerardinis says. “It’s the things you can’t see, the things underground — City projects connecting people to stormwater and watersheds, that makes a big impact.”

He also points to City programs, including the Germantown Waterway Arts Initiative and Wingo-WHAT? projects, which use art to not only connect people with the inner workings of these systems, but also allows people to process the trauma flooding causes.

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Water Department is continuing its combination of green and traditional infrastructure efforts in the area.

But, with few updates on the City’s efforts to begin building the Wingohocking Relief Sewer Tunnel, which could cost up to $800 million and take a decade or more to complete, and recent reporting on the mixed results of the Green City, Clean Waters initiative, residents are left to consider an uncertain future.

The City did not respond to requests for comment.

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoice-everyvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoice-everyvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.