It was September 1999 and Denise Statham didn’t know danger was lapping at her doorstep.

Her employer had closed their office earlier that day and Statham was finishing some work on her laptop when the power went out. She decided to nap for a while and see if it came back on. At about 7 p.m., she awoke to the sound of water sloshing around the finished lower level of her three-story rowhome.

“I looked down the steps and my washer and dryer were floating,” Statham says.

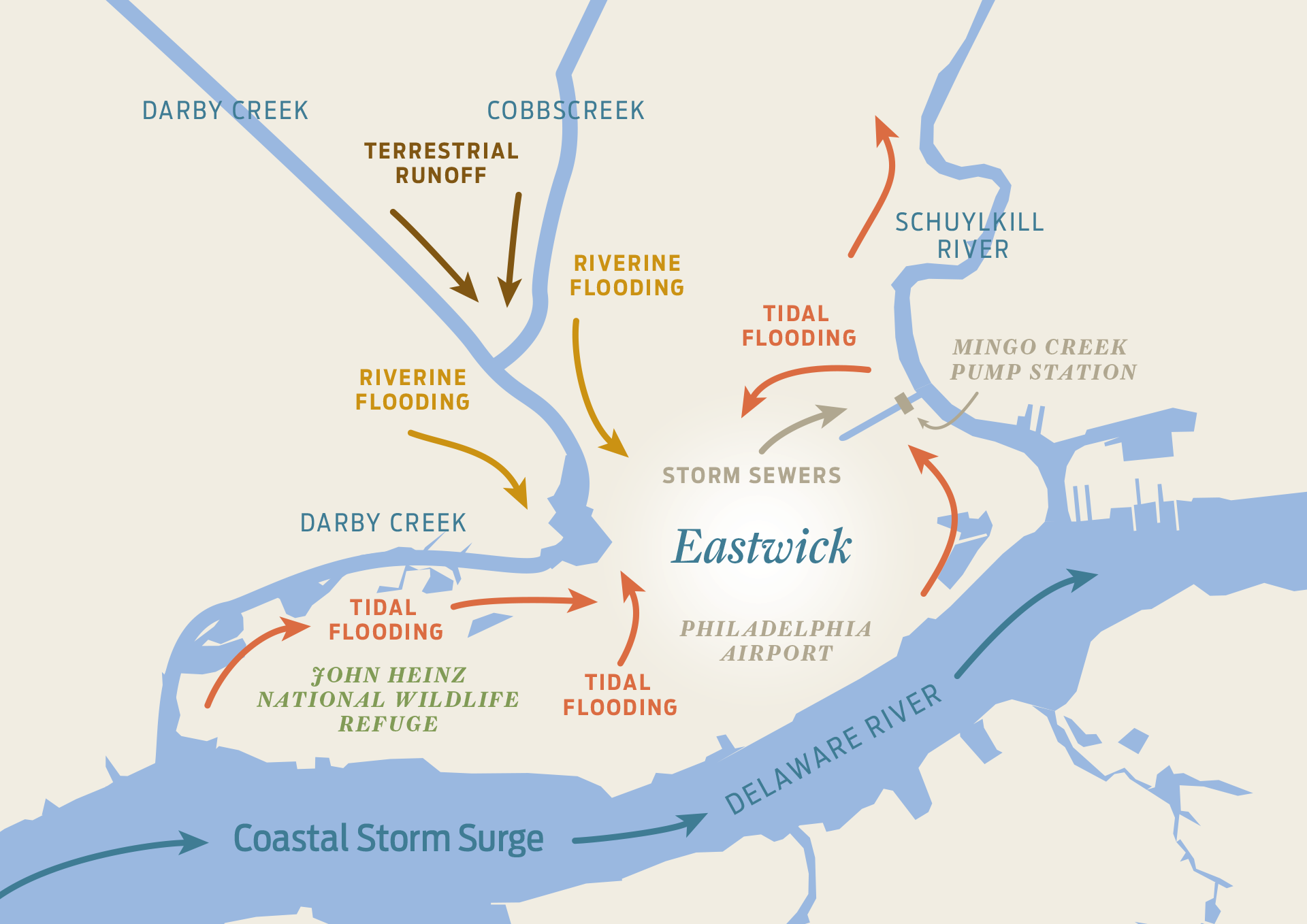

Hurricane Floyd was lashing Philadelphia, ultimately dropping nearly seven inches of rain in a single day, a record at that time. Statham was in her home on Venus Place in Eastwick, a low-lying Southwest Philadelphia neighborhood now well known for its propensity to flood. But at that point, Statham had lived in the home less than a decade and wasn’t prepared for what would come next.

Thinking a pipe had burst, she waded through the water to her garage where a valve for her water main was located. But seeing that her car was also submerged, she realized the flooding was coming from outside. She used her cell phone to call her sister.

“My sister said, ‘What are you doing there?! We’re watching your house on TV,’” Statham says. “That’s when I went to the front door and realized the magnitude of what was happening.”

She was the only person remaining on her flooded street. Her neighbors had left or been evacuated by National Guard boats while she was sleeping.

Statham emerged from the event physically unscathed, but it was one of just several times she and her neighbors have experienced severe flooding in the decades since. All the while, anger about a lack of solutions for chronic flooding in Eastwick has simmered, boiling over on occasion.

This summer came a fresh wave when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a draft study promoting a potential 1,400-foot-long levee to shield Eastwick from floodwaters from the adjacent Cobbs Creek, just above its confluence with Darby Creek. At first glance, it looked like a major milestone. At a community meeting in Eastwick in October, officials from the Army Corps and Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability promised the levee was a good faith, nearly shovel-ready proposal after decades of start-and-stop efforts that ultimately went nowhere.

“We can’t fix the flooding, but we can attempt to substantially reduce it,” says Stephen Rochette, executive assistant at the Army Corps. “We hear the frustration about the time that has elapsed. We are further along than we have ever been before.”

But from the earliest moments of the meeting and through the weeks and months that followed, it became clear the levee proposal would be no panacea. Residents, community organizations and government officials have expressed a range of opinions on the proposal with some in favor, some opposed and many still silent as they consider its merits.

Conversations about the levee quickly expand to other potential solutions. Some prefer that efforts focus on buying out and relocating residents from their homes, making flood insurance more affordable, or turning to nature-based solutions to soak up floodwaters.

Perhaps most ominously, it isn’t clear who will ultimately make a decision. There are dozens of entities who potentially could play a role, with the Office of Sustainability functioning as something like an air traffic controller. Decision making could range as high-level as incoming Mayor Cherelle Parker, down to street-level community organizations in Eastwick.

“We’re coordinating closely with partners, including City Council and community members, to inform decision making for the new administration,” a City of Philadelphia representative wrote in a statement to Grid, adding that a Flood Resilience Strategy set to kick off in 2024 will explore “how to shift as much of that decision making as possible to community-based organizations and residents.”

But where things stand with those community organizations is also presently an enigma. Influential groups like the Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition and Delaware Riverkeeper Network have largely been mum on the levee proposal. The Army Corps has pushed back its deadline for public comment on the levee proposal twice by community request, from November 2023 to the end of January as of press time.

Brenda Whitfield, an outspoken officer of the community organization Eastwick United CDC, said, as of mid-December, the situation remained “very complicated and complex.” Just a few weeks earlier, residents of neighboring communities in Delaware County — where Army Corps models show flooding could worsen if the levee is built — expressed deep concerns at their own public meeting about the proposal.

In a text message to Grid, Whitfield said that left the Army Corps with “their work cut out for them” in making sure Delaware County communities “are not getting extra floodwaters.” But at the same time, Whitfield lamented that Eastwick residents had not had a seat at the table in prior decades, when Delaware County communities made decisions regarding upstream infrastructure and land use she believed impacted conditions in her Eastwick community. Whitfield says she believes there have been at least “14 different levees, stormwater drains, dikes and private levees,” built in the county.

“So we will see how this plays out,” Whitfield said.

Jaclyn Rhoads, board president of the nonprofit Darby Creek Valley Association (DCVA), believes there’s a path forward. Her organization spans the entire watershed, with constituents in both Delaware and Philadelphia counties. Rhoads told Grid there is an effort underway by the DCVA, Friends of Eastwick, Riverkeepers and Friends of Heinz Refuge to craft a shared vision that includes a number of potential solutions. They were also in conversation with others, such as Eastwick United, Rhoads said.

[The City] needs to become a little bit more outspoken on what the community wants and what their vision is. Time is up.”

— Jaclyn Rhoads, Darby Creek Valley Association

If such groups could present a united front to powerbrokers, Rhoads believes it could create the impetus and pressure for the City to finally deliver a solution in Eastwick that’s not only actionable, but inclusive and holistic.

“[The City] needs to become a little bit more outspoken on what the community wants and what their vision is,” Rhoads says. “Time is up.”

Weighing the options

On paper, the Army Corps’ levee proposal has a lot going for it.

In materials passed out during an October 4 community meeting in Eastwick, a map of the area shows hundreds of green dots in Eastwick marking properties where the Corps believes a levee would reduce flood risk during severe storms. With levee construction costs estimated at $13 million and annual maintenance projected at $67,000, the cost-benefit looks very good, considering the Corps estimates a levee will reduce flood damages by $128 million over 50 years. The Corps proposal also says the federal government will pay for two-thirds of the construction costs.

Plus, a levee can give a real sense of physical security. At about 15-feet in height at its highest point, the levee would provide a tangible barrier higher than the flood levels reached during Hurricanes Floyd, Irene and Isaias, according to the Corps. For all these reasons, the Corps said, the levee was the preferred option over others it studied, such as relocating residents or fortifying homes.

But along the periphery, the faults of the levee proposal can be seen. The same Army Corps maps showing floodwater improvement in Eastwick show scores of properties facing extra flooding further upstream along the Cobbs and Darby creeks, including in Philadelphia’s Elmwood neighborhood and Delaware County’s Darby Borough, Colwyn Borough and Darby Township.

While the Army Corps says such “induced flooding” will likely be minimized by extra capacity at the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge downstream, Lamar Gore, refuge manager for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, says it isn’t clear to him that Heinz is currently capable of handling extra water.

At the October meeting, Gore instead floated his own proposal to convert over a hundred acres of undeveloped land north of the refuge, currently owned by the City of Philadelphia, into tidal marshland. Then, excess floodwaters from the confluence of the Darby and Cobbs creeks could be channeled through a culvert under 84th Street to the new wetlands, creating a “nature-based solution” to absorb the water from Eastwick without pushing as much into adjoining communities.

But such an arrangement would likely require Philadelphia to transfer the land to the federal government and the popularity of that proposal remains unclear within the confines of City Hall.

“I’ve talked to the City about this, the Corps, and some in the community have come to meetings where we discussed this, too,” Gore said in October. “Some modified version of a levee combined with a nature based-solution could work.”

As the October meeting wore on, further diversity of opinions emerged.

Statham, who told Grid she largely favors the levee proposal, also pondered whether the City could do more to upgrade and maintain sewer capacity in her neighborhood. Another resident wondered if an early warning system for impending floodwaters would be a good use of resources. Many talked about a long history of neglect and racial justice issues in the neighborhood, dating back to its very construction atop marshland. With skepticism that a true fix is coming, some, like 50-year resident Victor DiSalvatore, are eyeing a move.

“Of all these plans you guys have, is there a plan for relocation, a buyout of these houses, if this thing don’t work?” DiSalvatore asked.

“Yeah, buy us out,” a woman called out.

Such a proposal could have legs. In 2021, a team of residents and local researchers concluded a “land swap” could be one of the top options for Eastwick, moving about 250 residents from their current flood prone homes and constructing new residences on the same undeveloped parcel that Gore is eyeing for the potential nature-based solution. In recent news stories, local leaders admitted that some residents remain committed to the idea.

Then there’s the impacted Delaware County communities: how much say do they deserve? The Office of Sustainability currently says that any levee construction would have to be part of a larger plan to address induced flooding.

“When talking about this decision, it is important to note that the Army Corps plan is still incomplete because it does not account for induced flooding, or the floodwaters that could be routed elsewhere because of the levee,” the office told Grid in a statement. “Until induced flooding is incorporated into the plan, this decision will not come before the new administration.”

Exactly how much political power Delaware County and its communities hold remains to be seen, although WHYY reported in November that a portion of the proposed levee stretches into Darby Township and would thus require an easement.

What happens next?

The Office of Sustainability says it is holding a variety of monthly and quarterly meetings to try and work toward consensus on a solution. The efforts will increase next year, after the City launches a $500,000 initiative to “develop a community-driven Flood Resilience Strategy for the Eastwick neighborhood,” according to a public request for proposals that went out shortly after the October meeting.

“This will be a dedicated planning process to weigh the many different flood resilience options on the table and develop an implementation roadmap to bring those flood resilience measures into fruition,” the RFP stated.

Statham has assisted with the efforts. Her long history in the neighborhood reveals the complexity of the issue. She knows the housing stock of the neighborhood, dating to development by the Korman Company in the 1950s, is problematic. She too believes upriver communities like those in Delaware County have carelessly contributed to downstream flooding problems in the past.

We live here by choice … We live here for reasons, principles and values. There are people on every block that are settled and have been here … where are we going?”

— Denise Statham, Eastwick resident

And yet, she recoils at being referred to as a “marginalized” community and detests the idea of relocation. She’d rather see the money used to study such concepts go toward “low-hanging” fruit like storm drain cleaning and better warning systems. For her, mitigating the damages to the community as much as possible, as soon as possible, is the salve to long-running injustices.

“We live here by choice … we live here for reasons, principles and values,” Statham says. “There are people on every block that are settled and have been here … where are we going?”

For Rhoads, the latest flurry of activity in Eastwick holds new promise. In 2019, Delaware County Council turned Democratic for the first time since the Civil War and she says the new leadership is more cognizant of watershed management. Multiple other key players are at the table. A solution feels attainable if common ground can be found and political leaders can lead.

“It’s been a historical problem and now we’re getting to the point where people are now finally having conversations and understanding we need to rely on each other for the solutions,” Rhoads says. “This presents an opportunity to forget the past, move on, have these conversations and figure out a way to look at the future.”