Bekah Carminati spent her childhood making mud pies and inspecting insects in her backyard in Montgomery County. When she grew up, she took up landscaping as a way to channel her love for craft and nature.

But there was a problem. The company she worked for insisted on applying black dyed mulch, planting annuals and other gardening practices she sees as unharmonious with nature. “I did it for a season and ultimately was kind of repulsed by the whole practice of it,” she says.

So one year ago, the 24-year-old struck out on her own. She founded a one-woman landscaping company, Native Nymph Gardening, which has her installing native plants for 10 clients across Bucks and Montgomery counties. Carminati has joined the expanding ranks of landscapers, nursery owners and backyard botanists in the Philadelphia area who advocate for native plant gardening. Their humble goal: prevent total ecosystem collapse.

Though scholars debate the best definition, many consider native plants to be those that grew in a given region or subregion before European colonization brought new species, agricultural methods and ideas about the natural world to the continent.

Over millions of years, birds, bugs and other forms of life evolved alongside native plants and one another, forming balanced ecosystems suited to the area. When foreign species are thrown into the mix, they often leech valuable resources from those systems while offering little in return. At their worst, non-native plants can be invasive — metastasizing and choking out the flora that local insects and animals need to survive.

To see invasives in action, Carminati says, take a hike in the Wissahickon. Japanese barberry and multiflora rose plants — “prickly guys,” she calls them — were brought from East Asia and Europe in centuries past, posing a problem to the region’s native dwellers. When birds mistake their berries and rose hips for food, they don’t just miss out on more nutritious alternatives; they end up spreading the plants further, making the problem worse.

The menace of biodiversity loss can seem abstract and nitpicky to those of us who don’t spend our free time researching cultivars or pining for the return of the American chestnut. But when humans choose blank lawns and exotic species over their life-sustaining counterparts, the consequences echo all the way up the food chain.

“Whether or not people want to admit it, we are a part of nature,” Carminati says. Basic human needs like clean water, breathable air and fresh food all stem from healthy ecosystems, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

Carminati’s business idea, which began as a note on her phone, revolves around sustainable gardening practices — from replacing thirsty, ecologically functionless lawns with backyard meadows, to uprooting invasives by the wheelbarrow full.

Carminati’s unwavering embrace of all things wild sets her apart in the gardening business. Despite increased interest in the subject — Google searches for “native plants near me” in the United States rise year after year — preserving ecosystems is an uphill battle.

One of the most formidable obstacles is the popularity of the American lawn. A 2005 study led by NASA estimated that traditional turf lawns covered 40 million acres of the country. Lawns offer nothing to wandering critters in search of places to shelter or pollinate and often involve heavy water and pesticide use, yet hundreds of thousands are employed for their upkeep.

“The green industry is, for the most part, very un-green,” says Mount Airy landscape designer Brian Ames. Like Carminati, he started his own landscaping business, Wissahickon Landscape Design, out of frustration with the way profit trumped sustainability at larger companies. Every day for over a year, he worked a tree service job that exposed him and the environment to harsh chemicals, which left Ames feeling morally and physically unwell.

In his own work, Ames says he avoids pesticides, sources plants locally whenever possible and uses fall leaves as soil-enriching mulch rather than clearing them. Ames has found success in his “micro niche,” as he calls it, attracting a steady base of customers interested in native plants. But even with a solid Rolodex of eco-conscious clients, he says he can’t compete at scale with larger landscapers who cut costs via unsustainable means.

And there’s the added challenge that many consumers are reluctant to go all-in on native plants. Landowners may complain that they’re more difficult to maintain, attract unwanted pests, or just aren’t as visually stunning as Japanese honeysuckle, English ivy, gingko trees and other popular foreign options available at the local garden center.

Lee Armillei of Athyrium Design in Fort Washington, Montgomery County, sometimes struggles to convince clients not to fill their gardens with invasive species like burning bush. “They may have a hard time parting with it,” Armillei says. “Trying to talk them into taking that out and putting in something else that’s gonna be much smaller … that’s a challenge.”

Finally, knowing which plants to choose for a given setting goes beyond whether or not they’re native to the area. “A lot of times native plants are selected just because they’re native, but their long-term viability in the spot is no good,” Ames says. He looks at neighboring properties to make sure a plant will thrive in a specific microclimate.

For all his firmly-held beliefs on ecological gardening practices, Ames agrees that non-native plants can play a limited role in a healthy garden, whether as eye-pleasing ornamentals or to temper certain native species that spread and dominate like invasives.

“There’s definitely room for both [natives and non-natives], so long as the priority is supporting more [for the] ecosystem than for aesthetics,” says Carminati. Research has indicated that a 70 to 30 split between native and exotic herbage is acceptable in many cases, though even this modest goal is far from the norm.

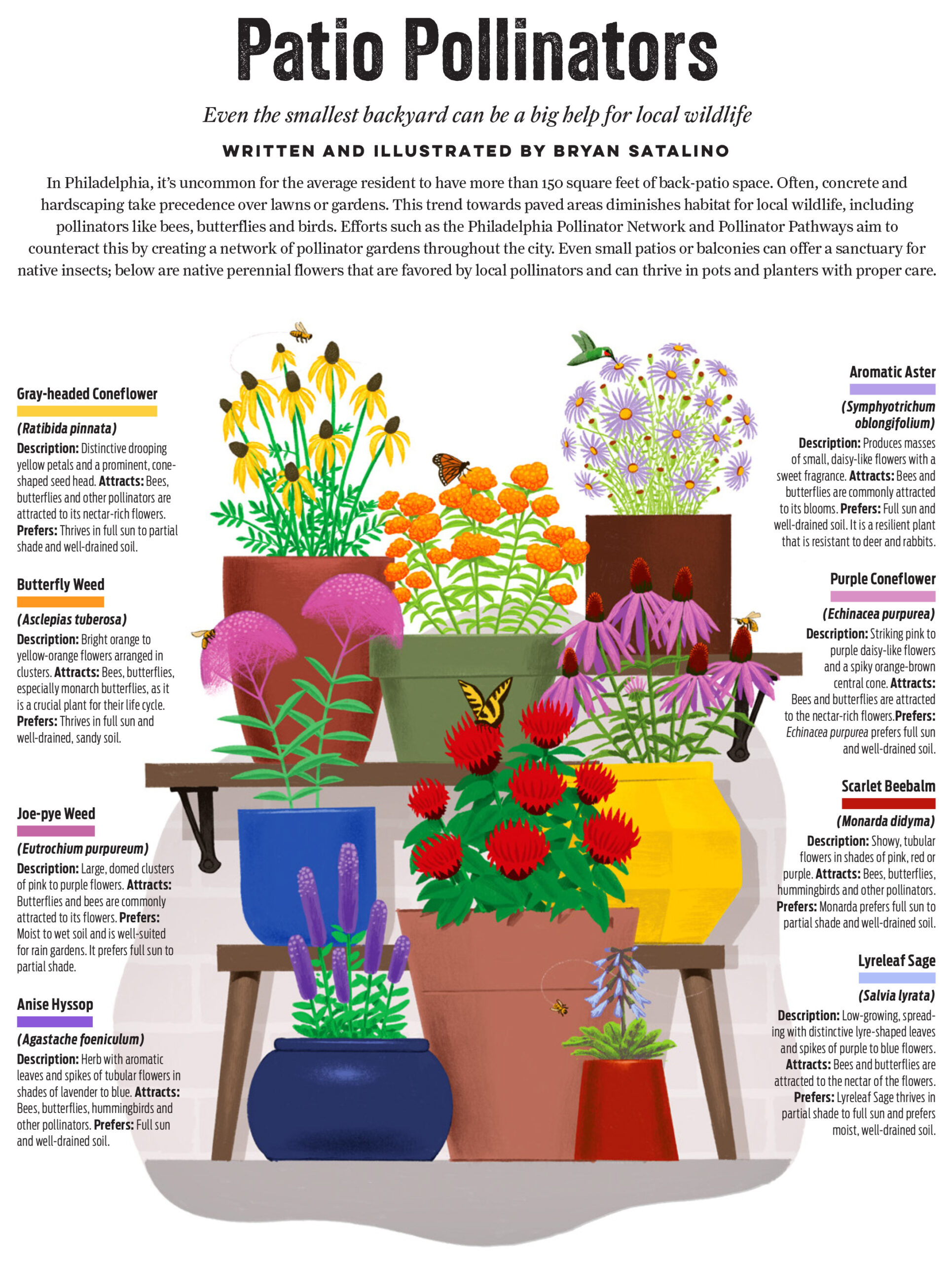

“You don’t have to hire some fancy business to do what’s right and to benefit the ecosystem,” Carminati says. Lawn owners can start by dedicating small sections of their garden to native plants, eliminating pesticide use and letting fallen leaves be in the wintertime. And city dwellers can hang container plants from their balconies to attract pollinators.

Looking forward to a busy spring season, Carminati has several installations on deck across the Philadelphia suburbs. When it comes to native plants — and the innate zeal for serving nature that drives her work — she will talk to anyone who will listen.

“Everyone needs to know,” she says.

Would have been an even better article had the gardeners mentioned names of native plants.