By Meg McGuire and Katherine Rapin

In December 2023, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency made a bold move for the Delaware River, proposing to raise the water quality standards in the estuary for the first time since the Clean Water Act of 1972. This upgrade would increase requirements for dissolved oxygen levels among the foundational requirements for survival of aquatic ecosystems and thus a key determiner of river health.

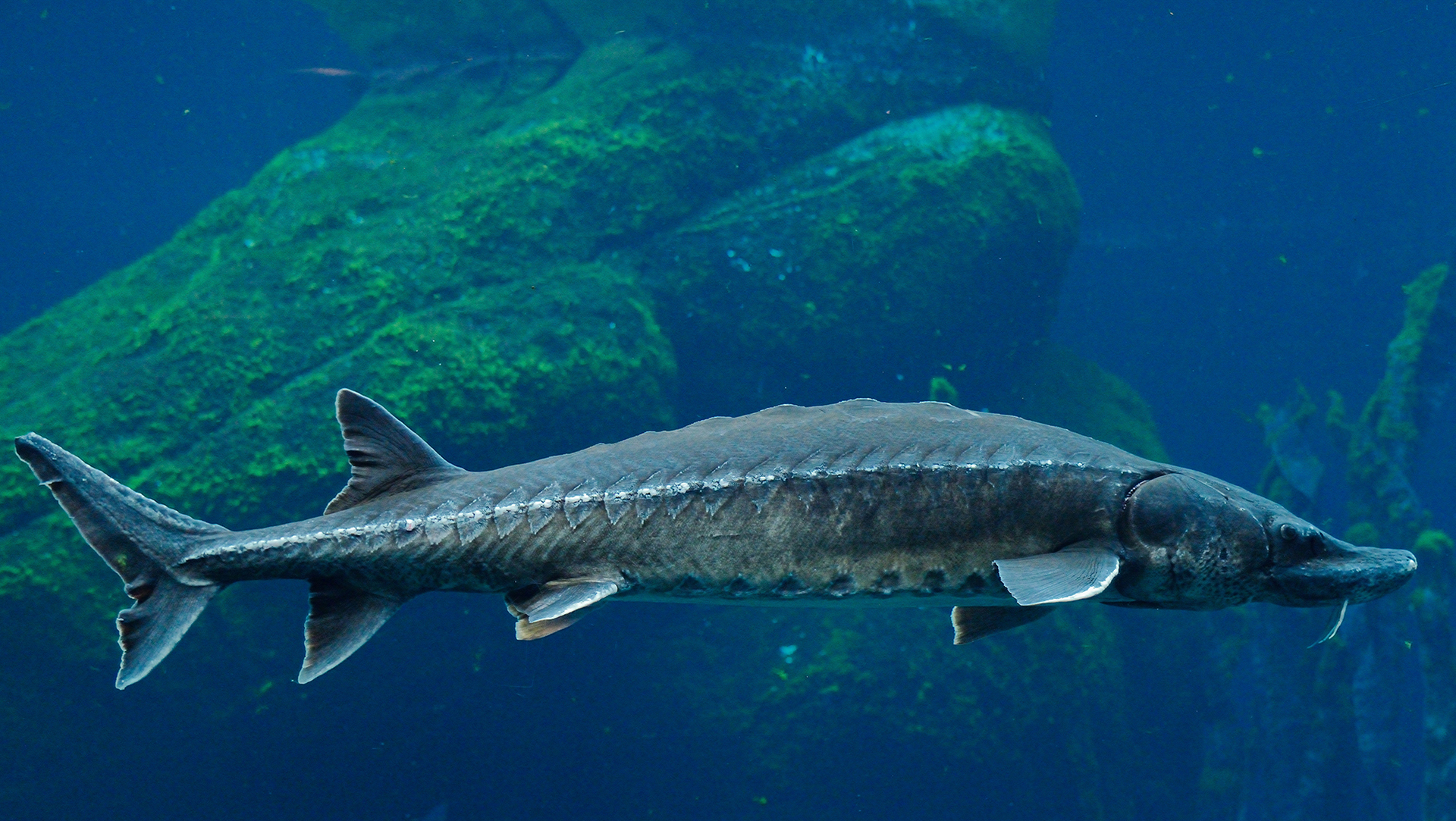

The EPA’s action came in part as a result of pressure from environmental groups that have for years rallied to demand higher dissolved oxygen (DO) standards in the estuary, largely to protect the endangered Atlantic sturgeon. This genetically unique population of fish, of which there are an estimated 250 breeding adults left, rely on the spawning and nursery habitats of the tidal Delaware River.

The increased standards are expected to dramatically improve the sturgeon’s likelihood of making a comeback — and support the recovery of the ecosystem in the urban stretch of the river roughly between Trenton, NJ, and Wilmington, DE. But the tricky part will be actually implementing solutions to increase dissolved oxygen levels.

Among the main culprits of low oxygen in the river is sewage. Human waste contains compounds like ammonia; bacteria and microorganisms in the water oxidize the ammonia, consuming (and therefore depleting) dissolved oxygen in the process.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of raw sewage — nearly one billion gallons each year, shows a recent PennEnvironment report — flowing into the Delaware.

In many cities, including Philadelphia, combined sewer overflow (CSO) systems allow stormwater to be funneled into sewer lines and carried to wastewater treatment facilities. If the storm is great enough, those treatment facilities get overwhelmed and untreated or partially-treated waste — including human waste as well as the universe of “stuff” we flush down our drains — pours into the river.

Upgrading these systems is necessary to improve dissolved oxygen levels and the health of our river as a whole. But the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD), whose wastewater treatments plants combined have the greatest impact on the estuary, isn’t supporting the EPA’s proposed standards. In a statement issued January 12, PWD wrote: “Simply setting DO criteria to the highest levels possibly attainable will impose burdensome costs on ratepayers with highly uncertain additional benefits to fish populations.”

Some environmental advocates, on the other hand, hope the EPA will go even further, and they’re making their voices heard before the EPA’s public comment period closes February 20.

How we got here

In the pre-Industrial Revolution era, when the population in the watershed was much smaller, our rivers could “treat” waste with the activity of hungry microbes. But when the load of that waste got too heavy, microbe activity was overwhelmed; back in the 1940s, the Delaware was basically an open sewer.

The Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), a compact among the four basin states and the federal government that has regulatory powers over the river’s water quality and quantity, worked with states and municipalities to develop wastewater treatment facilities to change that. In 1967, the DRBC promulgated new dissolved oxygen criteria for the river, but the urban stretch had less stringent criteria — reflecting the reality that, at the time, higher criteria weren’t achievable.

The most important problem to get solved in those days was the “poo” problem — all the carbon elements in the water. The wastewater treatment facilities the DRBC had supported across the watershed, funded by either grants from the federal government or low-interest loans and later boosted by the Clean Water Act in 1972, got a handle on that issue.

But the “pee” problem, which was considered secondary back then, is now front and center. Our urine contains high concentrations of ammonia, which depletes oxygen in the water and can have direct toxic effects on aquatic life.

Spotlight on the Atlantic sturgeon

Enthusiasts of the river might want the Delaware to be as healthy as possible simply for people, and in fact the aim of the Clean Water Act is to get all the waters of the country “fishable and swimmable.” What really gets the attention of the federal government, though, is when the water quality threatens an endangered species, in this case the Atlantic sturgeon.

The population of the sturgeon diminished from hundreds of thousands in the mid-1800s to just 250 breeding adults today for a variety of reasons, principally over-fishing more than a hundred years ago, continued ship strikes and oxygen depletion. The last threat affects young sturgeon in particular.

Before humans started interfering with the river, sturgeon had the run of it to spawn and the young could develop before heading to the open water of the Atlantic. Once we created that “open sewer,” there was almost a wall of less-or-no oxygen in that urban stretch. Though maybe an adult sturgeon could hold its breath (that’s not a scientific expression) and get through it, the young could not.

That patch where the dissolved oxygen supply can be low, especially during the summer, is the target of scientific inquiry and debate — and lots of arguments.

Costly upgrades

As PennFuture explains on their website, the “Clean Water Act requires that regulators determine the ‘existing use’ of a waterbody and establish a ‘designated use’ that matches or goes beyond the existing use.” The current designated use of the estuary, related to aquatic life, is defined as “maintenance of resident fish and other aquatic life” and “passage for migratory fish.” This doesn’t include protections for conditions that would ensure the ability for fish to reproduce.

Their right to be in the river is protected but not their right to have babies, even though studies have shown that fish are indeed spawning in the river.

In a resolution in 2017, the DRBC set out to determine the attainability of an upgraded designated use that included fish propagation rather than just fish maintenance in the estuary.

After investigation, in 2019 the DRBC identified 12 wastewater treatment plants that are significant contributors to the dissolved oxygen problem. They’re all municipal plants, including the Trenton, Camden and Gloucester, NJ, plants; the Wilmington, DE, plant; and three in Philadelphia.

Remember, these plants are municipal: All of them get money from customers to treat that wastewater. To some degree, they would all need to get more money from somewhere (state or federal programs, loans, grants, or taxpayers) to make the improvements required for the river to meet improved water quality standards.

And that next level of expenditure is significant, as outlined by the DRBC’s consultant, Kleinfelder, in a report in 2021. Willingboro Municipal Utilities Authority in New Jersey, for example, gets off “cheap” at an estimated cost of $52 million. The largest cost is for the largest city, Philadelphia, at a whopping total of $3 billion.

In the EPA’s documentation of its proposed rule-making, it would cost an annual average of $137.1 million over 30 years to meet its objectives, basing its projections on the DRBC-Kleinfelder study.

The high cost is in part why PWD is opposing the EPA’s proposed increase in dissolved oxygen standards. “Proposed new wastewater processes needed to comply with strict ammonia limits would have a significant financial impact on water rates … In PWD’s view, the costs and unintended environmental harms of the proposed changes may greatly outweigh the potential benefits to sturgeon and other forms of aquatic life,” they wrote in the recent statement.

PWD also mentioned their planned $70 million deammonification facility that will be built alongside the Southwest Water Pollution Control Plant starting in the summer of 2024.

Once constructed, the “facility will remove approximately 10% of the city’s load of oxygen-depleting ammonia at a reasonable cost and with a relatively small environmental footprint,” the department said.

To finance the project, the department said it was seeking a low-interest loan from the state’s PENNVEST fund and that it did “not anticipate a significant impact on user fees as a result of this project.”

But the move has its critics, namely Delaware Riverkeeper Maya van Rossum, who thinks the plan doesn’t go far enough:

“PWD is the largest source of DO-destroying ammonia discharges. The City has known for decades that there is existing technology to address this issue and that if they were unwilling to do so voluntarily that at some point they would be required to legally. To, at this point, only be addressing a small percentage of their ammonia discharges demonstrates a failure of leadership and a betrayal of the public trust,” she wrote in a statement to Delaware Currents.

Pushing for protection

For years, the Riverkeeper Network and others have advocated to get standards raised ASAP, and let the municipalities figure out how to do it, rather than conducting slow-moving studies.

In April 2022, the Delaware Riverkeeper Network was joined by Clean Air Council, PennFuture, Environment New Jersey and PennEnvironment in a petition to the EPA to step into that process since they felt the DRBC was acting too slowly for the sturgeon.

And surprisingly, in December 2022, the EPA agreed.

Then in September 2023, the DRBC ceded its authority for rule-making on aquatic life uses to the EPA.

In the new rules being proposed by the EPA, the required dissolved oxygen level is raised from its current 3.5 mg/L to three new sets of standards depending on the time of year — a reflection of the sturgeon’s sensitivity to oxygen depletion at different life stages.

And now, the EPA is setting up the timetable for public hearings (set for February 6 and 7) with a view to establishing these rules by the end of 2024.

This opens the door for next steps. It’s aspirational: What do we want our river to be in 50, 75 years?”

— John Jackson, Stroud Water Research Center

Although the EPA was moved to act in part by the pleas from environmental organizations, the Delaware Riverkeeper Network has criticized the agency as not going far enough to fully protect the sturgeon. Representatives from the organization urged the EPA to consider further increases to the proposed standards.

“It is essential that over the course of the next [several weeks], during the public comment period, the EPA take full stock of the science and lift their standards to the degree necessary to ensure future generations are able to enjoy witnessing a live, healthy and free-swimming Delaware River Atlantic sturgeon,” van Rossum wrote.

But others, like John Jackson, senior research scientist at the Stroud Water Research Center, encourage celebrating this potential progress.

In 2015, there were indications that the river was host to healthier fish populations than anyone knew, he points out. “But those populations weren’t recognized, weren’t protected. This opens the door for next steps. It’s aspirational: What do we want our river to be in 50, 75 years?”

This story was produced in collaboration with Delaware Currents and appeared in an earlier version on the Delaware Currents website.

Thank you for this excellent article! It was really informative- and I received an email from the Philadelphia Water Department on this issue as well (with their point-of-view)- so having more knowledge was really helpful.