On February 23, 2023, Philadelphia’s Department of Parks & Recreation (PPR) released the Philly Tree Plan: Growing Our Urban Forest. The product of two years of outreach and engagement that gathered input from more than 9,000 people, the plan attempts to chart a course to expand the city’s tree canopy while balancing the benefits of additional trees with the costs.

The trees of Philadelphia, taken together, offer enough environmental benefits to justify increasing their collective canopy: they provide shade to a city heating dangerously as the planet warms. They soak up rainwater that would otherwise surge into the storm sewer system and force sewage to overflow into waterways. They offer habitat to wildlife. They absorb carbon dioxide as they grow, helping to slow global warming.

As individuals the trees can benefit the people who live beneath them. They offer a break from the sun on a hot day, perhaps as you’re waiting for a bus that should have arrived 10 minutes ago. Some offer feasts for the eyes and the stomach by flowering and bearing fruit.

But these benefits don’t always come cheap. Some trees heave the sidewalk up, blocking the way for people using wheelchairs and forcing homeowners to foot the bill for expensive repairs. Trees don’t live forever, and a dead or dying tree can be dangerous, potentially dropping limbs or tipping over in a storm.

Lara Roman, a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service who was a member of the tree plan project team, has examined the tension in her own research. She was part of a team of researchers that published a study in 2022 looking at the barriers to tree planting in North Philadelphia, an area inhabited mostly by Black and Brown people. There is little tree cover, and residents there often work low-paying jobs, making it a high priority for tree planting initiatives that seek to correct decades of disinvestment and environmental injustice. The researchers found that even though residents might generally favor having more greenspace and tree cover, many are wary about taking on the burden and expense of tending trees after they are planted. “All in all, we identified a mismatch and tension between the ‘ask’ of participation in tree-planting initiatives and the current capacity of community members and leaders to accomplish equitable tree-planting goals,” the authors wrote.

In 2008, the administration of then-mayor Michael Nutter set a target to increase the city’s tree cover to 30% from what was, at the time, about 21% tree cover. The result? The City’s 2018 Tree Canopy Assessment found that the city had gained about 1,980 acres of trees. Unfortunately the city had lost 3,075 acres, for a net loss of 1,095 acres, a loss equivalent to about 1% of the city’s land area, or about 6% of the canopy.

The basic problem is that all the City’s efforts to plant more trees are no match for the work of developers and homeowners cutting them down. Trees are commonly victims of new construction, making it hard to retain canopy in a revitalizing city. On public land, decades of decreasing park budgets resulted in less mowing and landscaping. The woods crept into once-open areas, as happened on the Cobbs Creek and Karakung golf courses, where the Cobbs Creek Foundation cut down approximately 100 acres of trees as part of the courses’ renovation.

Many of the city’s street trees were planted when developers built Philadelphia’s neighborhoods in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The same is true of more-suburban neighborhoods that were developed in the mid–20th century in the northwest and northeast of the city, where many yards also came with new trees. Much of this canopy is being lost as these trees reach the end of their lives.

It can take a tree decades to reach full size, and many newly planted trees die within a few years. Thus, planting new trees to replace mature trees is generally a losing game. Additionally, many of the new trees won’t match their predecessors, even when they are fully grown. Current street tree plantings emphasize planting the right tree for the location, which often means using smaller species less likely to heave up the sidewalk. But replacing towering species of trees, such as London plane or red oak, with smaller species, such as serviceberry or kousa dogwood, results in a net loss of canopy, even once the new trees mature.

The City’s 2023 Tree Plan attempts to reverse the tree canopy slide with a long list of ambitious proposals. The first set has to do with focusing the City’s work to support trees, including hiring a City forester and coordinating the work of the various City departments and utilities that are involved with managing trees.

Most of the City’s tree canopy protections are part of the zoning code, which means that their enforcement generally falls to Licenses and Inspections staff who tend to specialize in building and construction safety rather than forestry. Inspectors might be experts in ensuring that electrical wiring won’t spark fires or that walls won’t collapse, but judging the health of a heritage tree tends to fall outside their wheelhouse. The City forester, along with a staff of seven, would inject much-needed tree expertise into zoning and land planning processes. The forester would also oversee the implementation of the tree plan.

If the plan comes to fruition, the forester will count on stronger tree canopy protections. The zoning rules dealing with trees will largely consist of requirements for how landowners replace felled trees rather than actual protections that keep people from cutting them down, but, if enacted by City Council, the stronger rules would decrease the size at which a native, healthy tree is considered a heritage tree (meaning developers would have to plant new trees to replace it), and would apply the tree code on smaller residential properties. These lots are currently exempted from replanting requirements, but they are where much of Philadelphia’s canopy loss is taking place.

Much of the rest of the plan boils down to the formidable task of getting the public on board with expanding the tree canopy. Although environmentalists might hug trees and welcome them as a matter of course, many Philadelphians lack the time and resources to support the trees they do have, and they are leery of new trees in their yards or on the street in front of their houses that will mean more hassle and expense as they grow and age.

In addition to communicating better with the public about trees in their neighborhood, the plan proposes additional community forestry and street tree staff who can help homeowners care for trees on their property and help remove trees that pose a risk of losing a limb or falling over. Dedicated customer service staff would be available to help tackle the thousands of tree-related requests that flow in via 311.

“Maintenance before planting to restore trust,” Roman says.

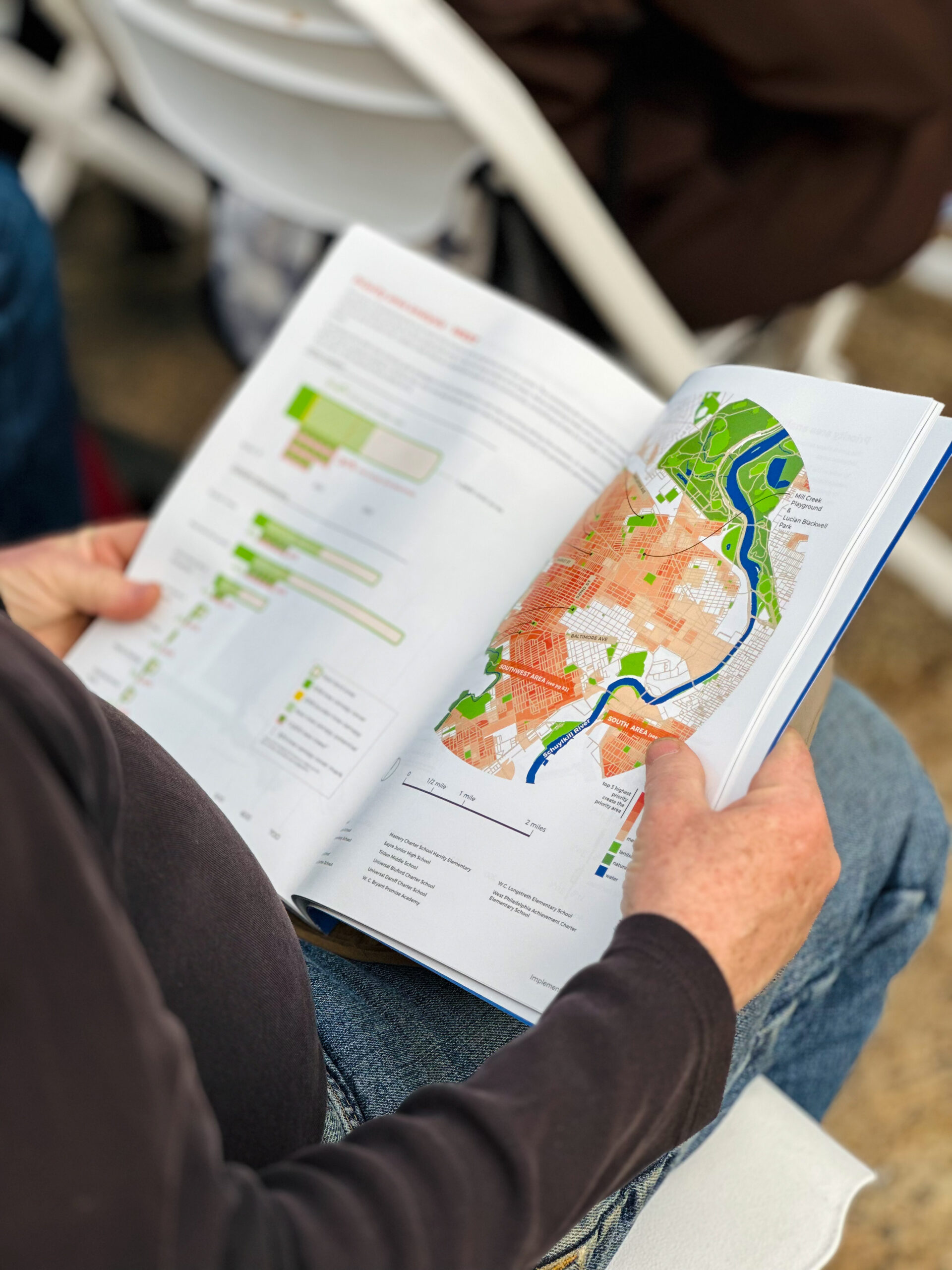

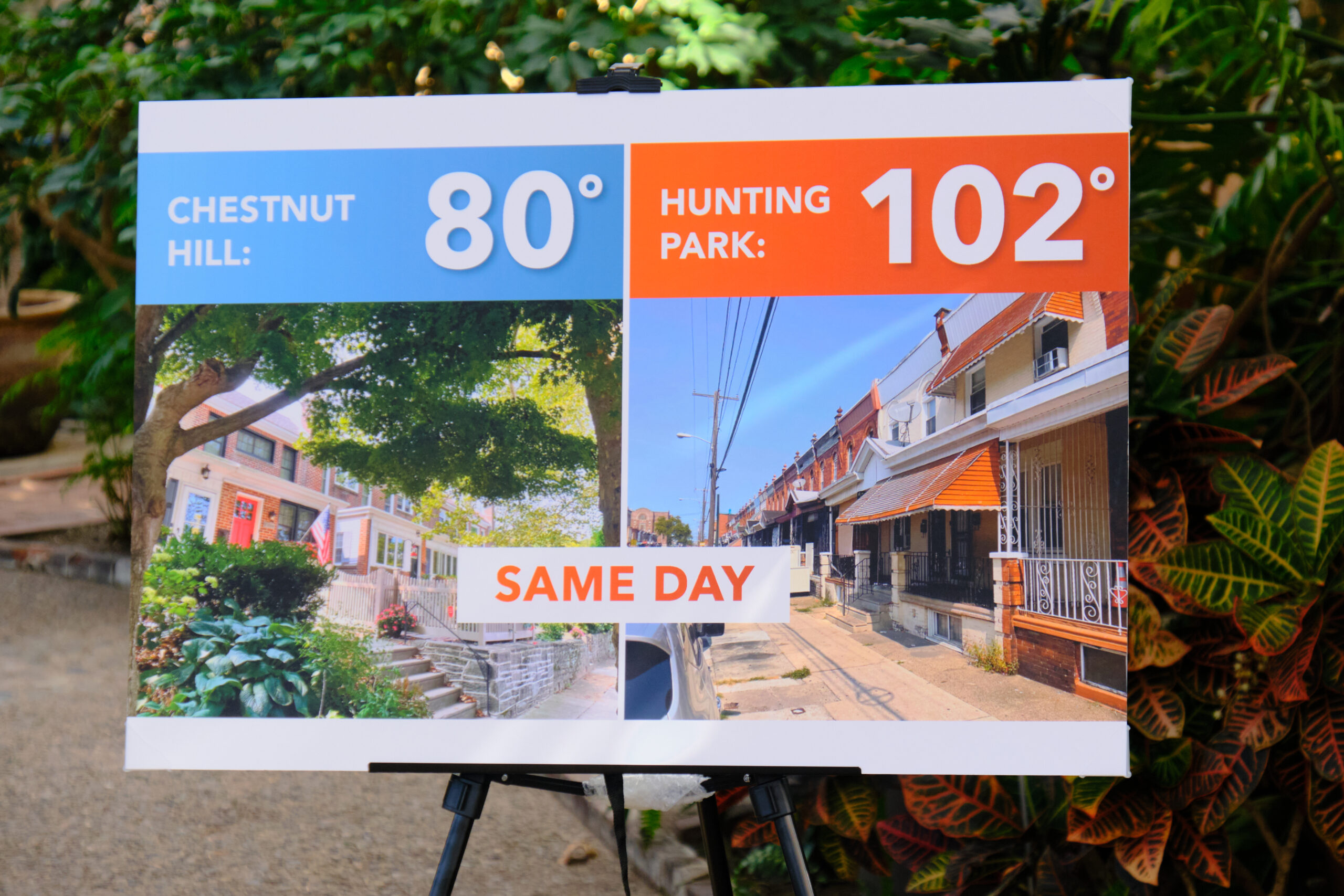

Not all the details are filled in. The plan calls for more-intensive planting activity in low-income neighborhoods that currently have the least tree canopy, where the houses and sidewalks bake unshaded every summer and temperatures can rise 20 degrees higher than better-resourced and better-shaded neighborhoods like Chestnut Hill. When it comes to exactly how to increase tree plantings in these priority neighborhoods, the plan stops short of specifics and repeatedly says that “strategies must be identified for new tree planting.”

Grid asked for examples of strategies that might be employed in low-canopy neighborhoods. “The Plan calls for prioritizing large-scale street tree planting (3.6) by organizing residential blocks, planting trees proactively along commercial corridors, and fully stocking street trees around public facilities,” a PPR spokesperson responded. She also pointed to Portland, Oregon; Washington, DC; and New York City as cities that Philadelphia could emulate, but did not offer specific examples of their street tree planting practices.

Beyond the implementation challenges, the big question is whether City leaders will follow through on it.

After high-profile tree clearings at the Cobbs Creek golf courses and at the Union League Golf Club at Torresdale, At-Large City Councilmember Katherine Gilmore Richardson introduced legislation seeking to tighten up holes in the tree code. It passed, but with amendments exempting City Council President Darrell Clarke’s 5th district as well as development for affordable housing and on some industrial land. More recently, City Council unanimously passed legislation introduced by Curtis Jones to exempt trees on the Cobbs Creek golf courses from zoning rules protecting trees on steep slopes, showing that even the City’s toughest tree protections are no match for councilmanic prerogative.

The plan will also be expensive to implement, costing an estimated average of $25 million per year over 30 years from an undefined mix of public and private sources. It calls for 67 extra staff positions. Philadelphia’s elected officials severely underfund operations at Parks & Recreation, so it remains to be seen whether they will increase the department’s budget to make up for whatever can’t be raised from outside sources.

In Grid’s recent election guide, all of the mayoral candidates voiced support for the goal of increasing the city’s canopy, but some were more specific than others about how to accomplish it.

Cherelle Parker voiced support for “an aggressive plan for urban tree planting” to offset loss from development.

Rebecca Rhynhart emphasized the use of data and mapping to focus efforts on neighborhoods in need of more tree cover.

Maria Quiñones Sánchez favors moving tree plan implementation from Parks & Recreation to the much-better-funded Philadelphia Water Department.

Helen Gym voiced support for several of the action items in the tree plan, such as increasing heritage tree protections and increasing tree planting requirements for new development. “Additionally,” she wrote, “I support the creation of an Office of Urban Forestry.”

PPR declined to make community forestry manager Erica Smith Fichman available for an interview. Roman credits Smith Fichman and her team with pushing the tree plan to completion and for thoroughly engaging the public in the process. “By engaging a variety of stakeholders, including residents and natural resource professionals, we have greased the wheels so implementation can actually happen,” Roman says.

Much needed across America