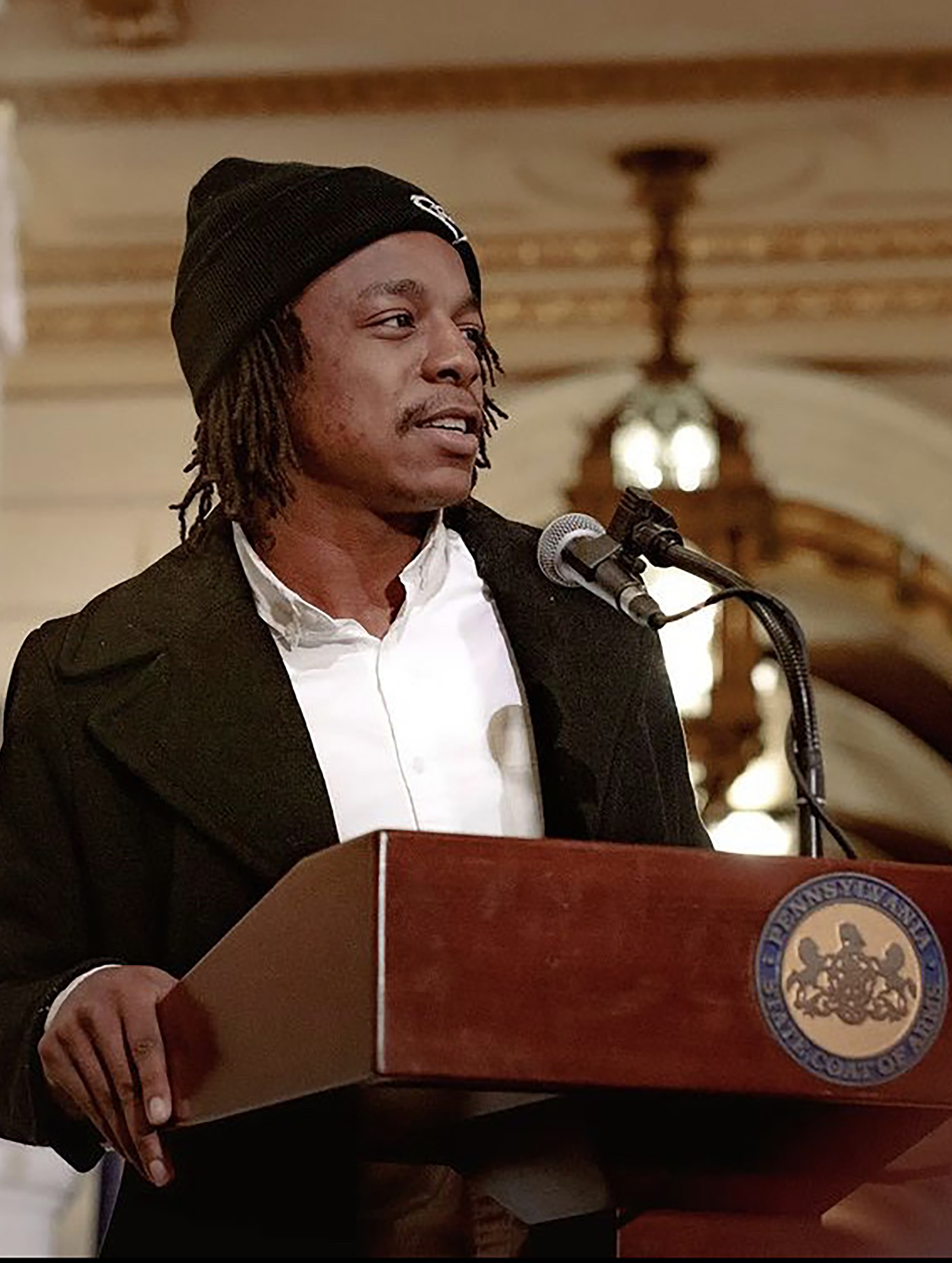

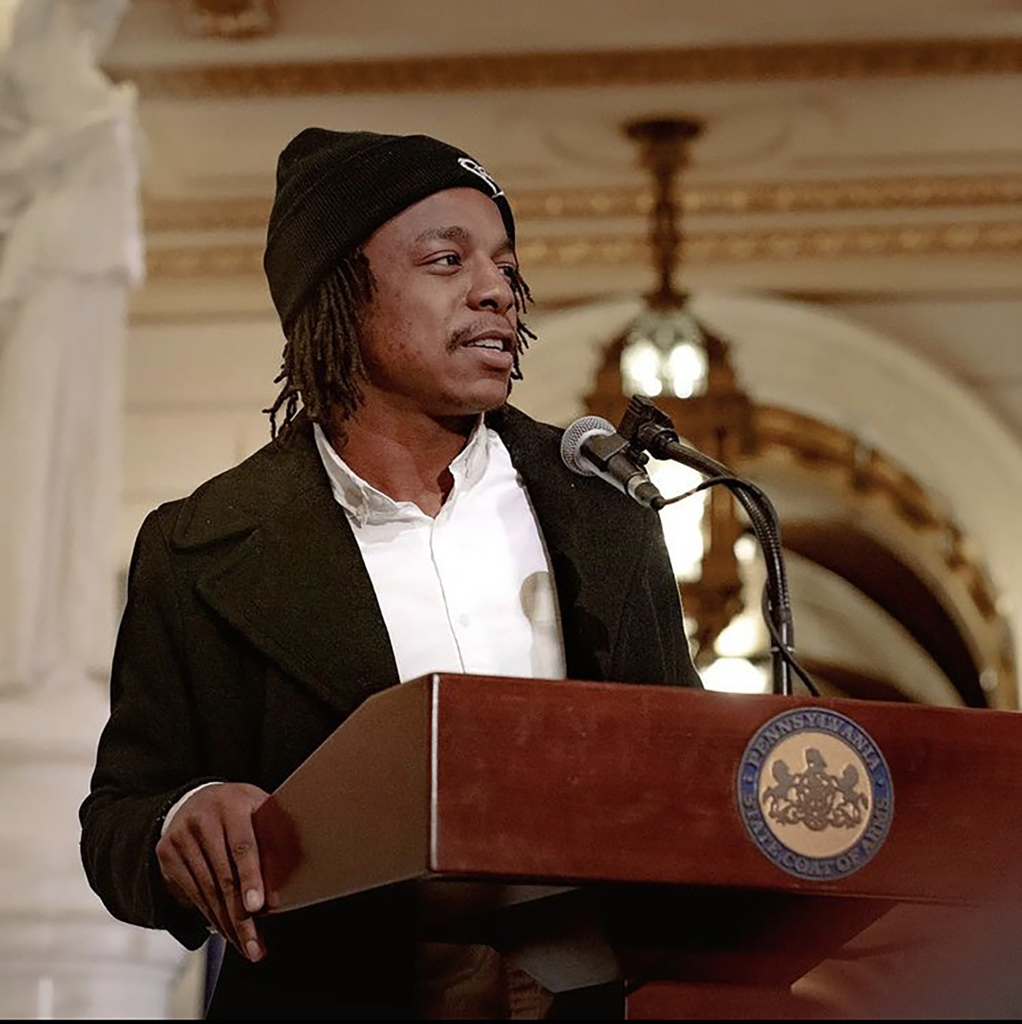

Convicted of attempted murder at age 17, Philly performing artist and musician Andre Simms, or DayOneNotDayTwo, his stage name, spent eight years in an adult prison. Released in 2021, he’s now the lead youth organizer with the Youth Art & Self-Empowerment Project (YASP), 924 Cherry Street, a group of young people working to reform the juvenile legal system in Pennsylvania.

“During the first four years, I spent half the time in solitary confinement,” DayOne, now 26, says. Post-traumatic stress still breaks through his life at times. “The other night, my partner dropped something on the floor, and I jumped up, ready to fight.”

DayOne’s case isn’t unique. As of October 2020, Pennsylvania youth prisons held 1,098 youths, according to No Kids In Prison, a national campaign to end youth incarceration and invest in community-based supports for young people. State Senator Anthony Williams, 65, co-sponsor with Camera Bartolotta, 58, of bills that revamp Pennsylvania’s juvenile legal system, cites a higher number.

“Some 3,612 young people under the age of 18 are in secure detention [including prisons and jails] in Pennsylvania [as of August 2022],” says Williams, who represents parts of Philadelphia and Delaware Counties.

While YASP, founded in 2005, works in Philly’s prisons, courts and neighborhoods towards effective youth justice, Sen. Bartolotta, Sen. Williams, State Rep. Chris Rabb and other legislators hammer out bills in Harrisburg to change the current failed racist juvenile legal system.

Problems take root years before young people enter the system, DayOne stresses.

“At school, children often sit in overcrowded classes,” he says. “They have limited arts programs, and often, no library. At home, children may face poverty and hunger. I was directly impacted by poverty growing up as were the majority of young people we work with at YASP.”

Other pressures may come into play.

“Seventy percent of youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health condition,” writes Daniel H. Gillison Jr., CEO of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), headquartered in Washington, D.C., in the spring 2022 issue of “Voice,” NAMI’s newsletter. In many cases, young defendants have experienced abuse, according to The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy center based in D.C. that seeks to reduce incarceration in the United States and address racial disparities in the criminal legal system.

“You’re punishing youth for being traumatized,” DayOne says.

Race often dictates who goes to prison in Pennsylvania. Black youth in this state are “5.7 times more likely than white youth to be incarcerated,” No Kids In Prison says.

Money, or the lack of it, also helps to decide who lands behind bars. “Overwhelmingly, youth of color who don’t have adequate defense end up incarcerated,” says Sen. Bartolotta, who represents Beaver, Washington and Greene Counties in Western Pennsylvania. She co-founded the Pennsylvania Legislative Criminal Justice Reform Caucus, a bipartisan coalition, with Philly’s Senator Art Haywood. “[Youth of color] make up two-thirds of young people held in pretrial detention.”

YASP and legislators have targeted problematic practices in the state’s juvenile legal system, including charging children as adults, incarcerating children with adults, removing children from their homes for low-level offenses and offering few alternatives to detention.

Reform bills SB1240 and SB1241, developed by Sen. Bartolotta, their primary sponsor, build on recommendations in the June 2021 report of the Pennsylvania Juvenile Justice Task Force.

“Task force findings show that most youths are not headed toward adult crime,” Sen. Bartolotta says. “The research shows that juvenile justice should focus on rehabilitation, not punishment.”

Charging children as adults is an area of concern for good reason, says the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in Washington, D.C. Children and adults are different, AACAP stresses. Youth tend to make less judicious split-

second decisions and to have less impulse control than adults, according to AACAP. Pleasure-seeking and peer pressure also sway young people more, the organization says.

In the past, charging children as adults appealed to some authorities because it allowed longer prison sentences. But more prison time doesn’t necessarily mean a safer citizenry, AACAP says. It hangs a millstone around the young person’s neck.

Youth tried as adults “are no longer eligible for federal or state loans for education or housing, … increasing the chance that they will remain involved in the criminal system,” says AACAP’s position statement, “Adjudication of Youth as Adults.” “Also, convicted youth cannot vote in most jurisdictions which only serves to further marginalize these young people,” the statement adds.

One of Sen. Bartolotta’s bills raises the age for trying children as adults from 14 to 16.

“The bill also requires prosecutors to show a need for treating young people as adults,” she says. “Prosecutors could no longer send the case to adult court directly.”

Treating young offenders as adults may backfire in another way.

“Research shows that adult prosecution can make kids more likely to continue committing crimes, which makes the whole community less safe,” says Sen. Bartolotta.

Incarcerating children with adults has also come under YASP’s and Sen. Bartolotta’s scrutiny.

“[Adult prisons] are dangerous for youth physically and emotionally,” DayOne says. “I had to fight all the time. And it’s unhealthy for young people to be locked in a cell 23 hours a day.”

The Equal Justice Initiative of Montgomery, Alabama, pulls no punches on this topic. “Children under 18 held in adult jails and prisons are at great risk of sexual and physical violence,” the group says, noting that the majority of states still allow children to be confined with adults.

“Sometimes, kids as young as 13 are in jail with adults while waiting for trial,” Sen.Bartolotta says. “They haven’t been found guilty of anything. They’re missing school, [social] services and family while they wait for a court date. The situation increases the likelihood of recidivism. In other words, communities end up less safe.”

In addition, children in adult prisons may forego rehabilitative programs, such as vocational training, often available in youth detention centers, The Sentencing Project says. Such opportunities can help young people find employment and succeed after leaving prison.

Young people in adult facilities may lack access to arts programs that can encourage rehabilitation through introspection.

“I developed and facilitate Ascensions, a series of creative writing, music and poetry classes for youth,” DayOne says, speaking of workshops he gives at the Riverside Correctional Facility [on State Road in Northeast Philadelphia] on Saturdays and on weekdays in the wider community. “It’s a chance for young people to express themselves. We compose socially responsible hip-hop to combat the culture of violence. I found journaling and writing cathartic when I was incarcerated. I wrote my debut album when I was in prison,” he says, adding that adult prisons may also lack the mentoring accessible at some youth detention centers.

Separate detention facilities for young people can become a matter of life and death. Youth in adult prisons are nine times more likely to commit suicide than those in juvenile facilities, the Equal Justice Initiative says.

YASP and Sen. Bartolotta also seek fewer placements in detention centers for misdemeanors. The juvenile legal system slams young people of color in that respect too, The Sentencing Project points out.

“Some of the largest racial disparities exist for Black … youth, especially boys,” The Sentencing Project says. “[They get] the most punitive system response, including removal from the home and prosecution as adults.”

Sen. Bartolotta questions pulling young people away from their families and potential community support for low-level offenses.

“In 2018, two-thirds of children in youth facilities were there due to a first, nonviolent offense,” she says. “It’s inefficient. It costs $211,000 per child per year. On the other hand, family therapy costs about $3,700 per year, and you have the possibility of strengthening the emotional health of the entire household.”

In addition, placement outside the home may not provide safety or rehabilitation. In the spring of 2019, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services revoked the license of Delaware County’s Glen Mills School, the nation’s oldest reform school, due to allegations of staff abuse of young residents. In 2017, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported “death, rapes and broken bones” at the Wordsworth Academy, which billed itself as a treatment center for troubled youth, on Ford Road in Wynnefield Heights. It was closed after the asphyxiation death of Black teen resident David Hess during a struggle with staff.

YASP and Sen. Bartolotta also zero in on offering alternatives, or diversion, from the court route that leaves youths with a criminal record.

“Data show that diversion is a successful alternative, but most kids aren’t given the opportunity, even for a first offense,” says Sen. Bartolotta. SB1241 supports diversion from the court system.

Likewise, YASP has pioneered the Healing Futures Restorative Justice Diversion Program as a more reparative approach. Kempis “Ghani” Songster, 50, who entered prison at age 15 and served 30 years, heads the program. Begun in 2021, Healing Futures receives pre-charge cases from the district attorney’s office.

“Our program seeks to bring together the responsible youth and the person harmed for a restorative community conference,” says Songster. “Everyone who attends, including both parties and their supporters, works toward a restorative plan for the young person to repair the harm. Once the youth completes the plan, no charges are filed. The young person has no record.”

It isn’t an easy path, according to Janelle Harvey, 33, a healthcare clinician.

“A group of youth assaulted me,” she says. “Staff from the D.A.’s office presented the possibility of rehabilitation as an alternative. The diversion was challenging. It took a bit of soul searching.” She credits her interest in behavioral health for swaying her toward the restorative-justice route.

“I kept in mind that it’s easier to rehabilitate a child than an adult,” says Harvey. “If they went to prison, they wouldn’t get the help they needed.” She also weighed the effect of peer pressure and other possible factors. “They could have been exposed to violence and pornography growing up. Yes, I was traumatized, but it could have been much worse. Most people look for money, community service, or both, as reparation, but above all, I wanted to see a change in their attitude. I saw that at the meeting.”

Songster believes that the meetings are hard but empowering for all concerned.

“The responsible youth gets a better appreciation of the impact of their behavior on the person involved, on their family and the larger community because concerned community members attend the meetings,” Songster says. “The youth develops a greater sense of responsibility. The meetings also empower the person harmed because they get a say in how the harm will be repaired.

Songster continues, “The most challenging part of the program is getting people to see that there’s a way to handle the situation besides putting young people behind bars. Sometimes, the youths are ready to participate [in restorative justice] but the parents object.”

Songster himself seems to find continued healing in leading the program. “Years ago, I did someone irreparable harm,” he says. “Now I can help young people succeed.”

While YASP staffers keep track of young people entering the juvenile legal system, they also take a preemptive stance. “We have leadership-building workshops at schools and colleges to help youth avoid legal trouble,” DayOne says.

YASP also offers practical help for youths who face court dates.

“We have a Youth Participatory Defense Hub,” DayOne says. Begun in 2019, it helps show young people how to present themselves in court.

In addition, YASP helps young people who’ve left prison find employment, continue their education, take arts classes and rebuild their lives in other ways.

“What’s most challenging about this work is that so many institutions work against us,” DayOne says. “Fighting systemic racism and conditioning from centuries of oppression sometimes feels like an uphill battle.”

Yet, he finds satisfaction in furthering YASP’s goal of ending youth incarceration.

“We’re not just working to end inhumane, ineffective and racist practices,” he says. “We’re working to build a new world where all young people have a chance.”

Resources

“Stolen Dreams: The Impact of Trying & Locking Up Young People as Adults,” a 27-minute YASP YouTube video features incarcerated youths and their families.

The Atlantic offers an 11-minute YouTube video, “Inside Juvenile Detention.”

Youths may remain incarcerated due to lack of bail money. Philadelphia Bail Fund posts bail for people who can’t afford it. Stuck in jail, youths risk falling behind in school and missing a chance to show changed behavior during their day in court. See phillybailfund.org

YASP welcomes donations. Call (267) 577-9277 or visit yasproject.wedid.it

The Juvenile Justice Center

Juvenile Justice Center of Philadelphia (JJC) “helps prevent young people from entering the child welfare and juvenile justice systems through supportive services,” says Jeanine Glasgow, 53, executive director of the nonprofit founded in 1976.

Programs at JJC, with offices in Southwest Philly and Germantown, include intensive therapy, mentoring, in-home detention with support, truancy prevention and intervention, among other services.

To step up prevention, JJC recently launched a Community Evening Resource Center in Germantown. “It’s open from 7 p.m. to 2 a.m.,” Glasgow says. “Youth have structured activities and mentoring.”

For more information, see juvenilejustice.org or call (215) 849-2112, ext. 5506. JJC welcomes donations.

For more information about YASP, contact info@yasproject.com or call (267) 571-YASP.