“The only thing you absolutely have to know,” as Albert Einstein once said, “is the location of the library.”

When it comes to Philadelphia’s public schools, Einstein’s dictum leaves most students hamstrung, as the district’s number of librarians has declined sharply in recent decades.

“In 1991, the School District of Philadelphia had 176 paid librarians,” says Debra Kachel, advocacy committee co-chair for the Pennsylvania School Librarians Association. “By our best estimate, that number has dropped to four. Philadelphia may have the worst public school library system in the U.S.”

Thank goodness for exceptions. Eric Hitchner, 33, an English teacher at Building 21, a public high school in West Oak Lane, took a box of books into his classroom five years ago.

“The students got excited and asked if they could borrow them,” says Hitchner, a poet. “I realized we needed more than a shelf of books.”

The library has grown to a room with some 4,000 books.

“Eric started the library, I called it the ‘Field of Dreams Project’—‘If you build it, they will come,’” says Brianne MacNamara, 37, Building 21’s principal. “That has proven to be true.”

The library drew in more staff and colleagues.

“Eric’s been working on the library for several years,” says history teacher Jared McElroy, 41, who hand-sawed wood for bookshelves. “Without shelves, you just have stacks of books. Ultimately, one person can’t do everything.” McElroy also helped haul books and furniture up three flights of stairs.

“I’ve had help from most of the staff,” Hitchner says. “That includes book and magazine donations.”

“I’ve had help from most of the staff,” Hitchner says. “That includes book and magazine donations.”

McElroy brought in four James Baldwin books for the library after a student requested one. Faculty and staff also offered encouragement and helped with brainstorming.

“This year, my principal didn’t assign me a new advisory and instead gave me that prep time to focus on the library,” Hitchner says. “And there’s a contingent of folks who volunteer to chaperone when we go on trips [to meet book authors].”

Strangers have also jumped aboard.

“When book vendors learn I’m building a library, instead of charging me $10 or $20, they’ll donate a box of books,” Hitchner says.

The library demanded not only time and cash but soul-searching.

“You have to be careful not to play at being the white savior,” Hitchner says, noting that Building 21’s students are 98% young people of color. “It would be a disservice to who our students are. You have to be constantly mindful of how you approach the work.”

Hitchner found ways to embed skill-building in lessons and give students a stake in the library’s growth. He had students make bookmarks and write messages on them. One says, There’s no hood like motherhood.

“It honors students who are parents. They’re a segment of our school population,” Hitchner says.

He adds that students did research to find books in Spanish for ESL (English as a Second Language) students.

Building 21 students do a senior project that engages the skills and knowledge acquired throughout their academic career.

“It may be career-based or passion-based,” Hitchner says, noting that the library can serve as a resource for projects. “For example, one girl, Samirah, wanted to learn [American Sign Language]. She posed questions such as: ‘Why isn’t it one of the languages taught in school?’”

The library has become a refuge for some students, who take advantage of the chess board to get in a game. Hitchner envisions more.

“If we had a little more shelving, we could maximize the space,” says Hitchner, who’s eager to add to the collection of diverse books.

“The students have also expressed interest in doing a mural and getting the technology to self-publish a school anthology.”

Hitchner’s chief goal remains introducing more children to the pleasure of reading.

“I ask students to take a reading pledge,” he says. “If students have a young person in their life, maybe a sibling or a neighbor, that student can pledge to read to them, then choose a free book. You can take a new pledge every month. Reading is vital to a child’s ability to learn and be successful,” says Hitchner, who is married and the father of two small children. “It doesn’t happen automatically.”

The school’s closing due to COVID-19 interrupted the training of the library’s student volunteers. “I started as a library intern in my junior year, but I really dove in during my senior year,” says Egypt Luckey, 19, who graduated in 2020. “[As an intern] I carried books upstairs and put them into the system so that we had a digital catalog. The library holds a special place in my heart.” Luckey works in a bookstore on a college campus now.

The project also has borne fruit in other ways.

“Some retired librarians have offered to come in and help,” Hitchner says. “Colleagues have made space for a Little Free Library in the school’s community garden so neighbors can stop by and get free books.”

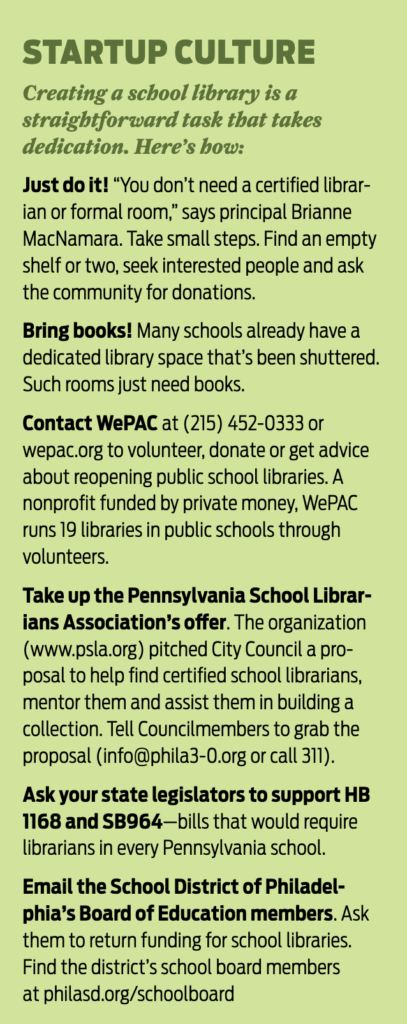

Hitchner sees a possible coalition of groups working to open school libraries. “I’m in touch with WePAC,” he says of the West Philadelphia Alliance for Children, an organization that reopens closed elementary school libraries.

School libraries provide more than a place to research papers or dive into fiction.

“Colleges expect students to know how to use a library,” says Kachel, of the librarian association, who also teaches online courses for Antioch University Seattle’s Library Media Endorsement program. “School librarians also teach students how to evaluate online sources, which affects their whole lives. They’ll have to assess information when they seek medical guidance or buy a house or a car.”

“A lack of money isn’t an excuse to cut libraries,” Kachel says. “Choices are made on how to allocate money. Priorities need to be set by thinking about what’s best for kids. People have to stop and say, ‘What we’re doing is damaging our kids.’