Music therapy can ease distress at life’s beginning, help us say needful words at life’s end and restore us in rough spots along the journey, according to Scott Horowitz.

Horowitz, 38, a board-certified music therapist and assistant clinical professor of music therapy and counseling at Drexel University, offers an example: “Re-creating the soundscape of the womb—the whooshing sound of amniotic fluid using an ocean drum, along with a gato box, a drum that can simulate a mother’s heartbeat—can help to stabilize premature babies.”

Music therapists can also guide patients toward peace at life’s end.

“Hospice patients doing life reviews may find comfort in listening to songs they enjoyed with their partner,” Horowitz says. In one case, a dying woman, with the support of a music therapist, wrote a song to thank the person who had become her caregiver.

Through music therapy, families may obtain audio keepsakes from a loved one. It could consist of recorded songs sung by the dying family member or a combination of songs and narrative. In addition, a stethoscope adapted with a microphone can record a heartbeat that’s then integrated into a piece of music, Horowitz says.

“It’s a powerful way to hold onto a person.”

How music therapy looks varies from patient to patient, notes John Glaubitz, 40, a therapist at Magee Rehabilitation Hospital. “Treatments by music therapists may include creating, singing, moving and listening to music, sometimes combining those approaches, to achieve physical, emotional, speech and cognitive goals.”

When stroke patient Richard Deen, 63, arrived at Magee with his left side paralyzed, Glaubitz suggested playing the xylophone and drums. “He had a percussion background, and I could raise the instruments so that he played while standing for ten minutes—one of our therapeutic goals,” Glaubitz says. “Drumming … kept him engaged and improved coordination between his left and right hands. Sometimes it’s a matter of shifting patients’ focus to something that engages them.”

The change of focus through music has proven especially important during the pandemic, when patients can’t have visitors, notes Siera Hall, 22. Hall, an animal science major, was helping to distribute hay to horses at the Penn State Horse Farm in State College last November when a 546-pound bale of hay fell on her. “It literally folded me in half and broke my back in two places,” she says. “A bone splinter severed my spinal cord. I’m paralyzed from the waist down.”

Glaubitz knew that Hall had endured other medical challenges—a brain tumor at 14, heart surgery at 15 and Crohn’s disease at 16—and that her father plays the guitar. Glaubitz recommended that she learn to play the ukulele.

“Playing lifted my spirits and helped me get through the pain,” says Hall, who plans to work with horses as a career. “If you’re not in a good place emotionally, you’re not going to benefit as much from other therapies.”

Hall capped her inpatient stay by writing an upbeat song titled “It’s Always Something, But It’s Never Too Much.”

Music therapy has venerable Philly roots. Two early references appeared in 1804 and 1806 in dissertations by students of physician and psychiatrist Benjamin Rush (1745-1813), who championed using music as medicine. (Rush also signed the Declaration of Independence.)

The field grew after the World Wars, when medical staff found that hospitalized soldiers healed faster with music. Colleges began offering music therapy studies in the 1940s. In 2011 the field made headlines when music helped former U.S. Representative Gabby Giffords recover after an assassination attempt left a bullet wound in her brain.

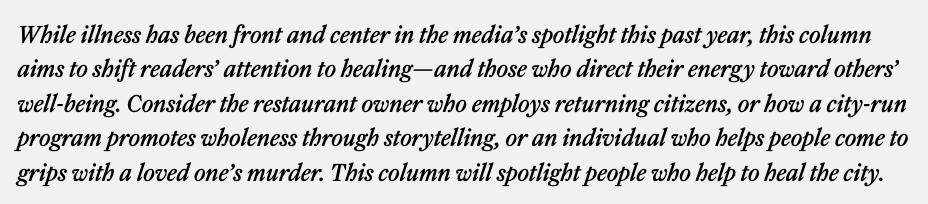

While music therapy can aid individuals with everything from pain to autism, it’s also helping to address big social challenges, says Peggy Tileston, 65, coordinator of clinical training at the Boyer College of Music and Dance at Temple University. “Atlanta, San Diego and other cities have homeless choirs,” she says. “Participation builds self-confidence and trust.” Formed in 2014, The Dallas Street Choir has performed at Carnegie Hall.

Karen Anne Melendez, who trained largely in Philadelphia, uses music to help heal the hearts and minds of inmates in a special needs unit at a women’s maximum-security prison in New Jersey.

Melendez uses singing, gentle movement to music, playing instruments and discussing song lyrics with inmates. “The women involved note tremendous enjoyment of the process, changes in their demeanor, [increased] social engagement with each other and self-confidence … ,” Melendez says. “Most years, we’ve presented a concert, but we cancelled this year due to COVID-19. For many of the women, it’s been the first time they’ve ever experienced success.”

Pamela Draper, 36, program manager of the Kensington Storefront, a community center and an initiative of Mural Arts Philadelphia, also saw gains from her Wednesday morning Community Music Hangout. “Anyone could walk in and participate,” Draper says. It led to “improved self-esteem … [and] social cohesion. We’ve had virtual open mics and art salons since the pandemic, but it’s harder to have the same level of trust in that platform.”

Yet the need seems great now, notes Natalia Alvarez-Figueroa, 31, a certified music therapist. “I work largely with Black people, Brown people and immigrants,” says Alvarez-Figueroa, who is of Black and Hispanic heritage. “Music therapy helps them feel more supported while they face illness, death and job loss.”

Drexel’s Horowitz also emphasizes reaching underserved communities. Many insurance companies consider music therapy a complementary service and don’t cover it, he explains. He would like to see music therapy become a primary service.

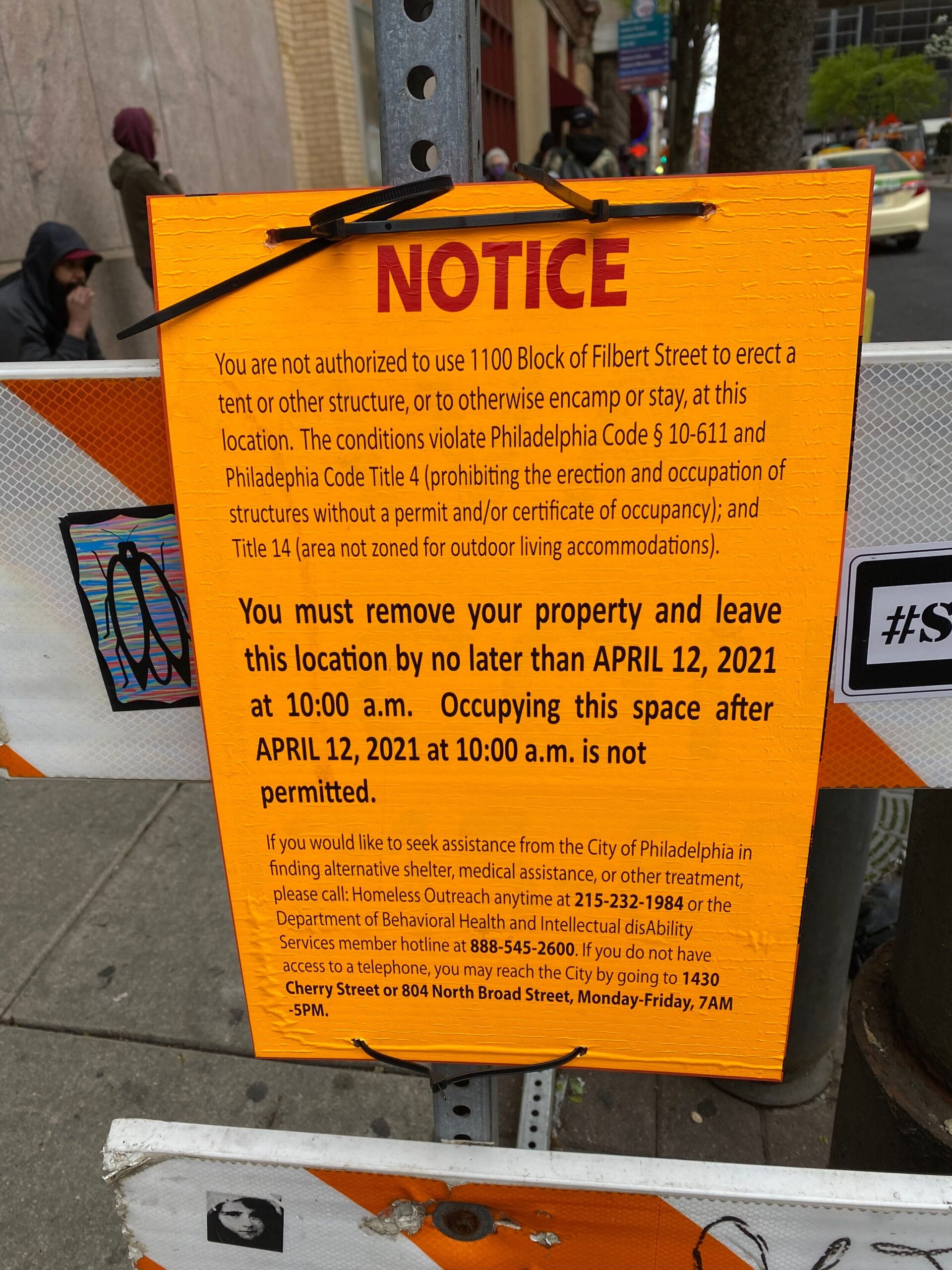

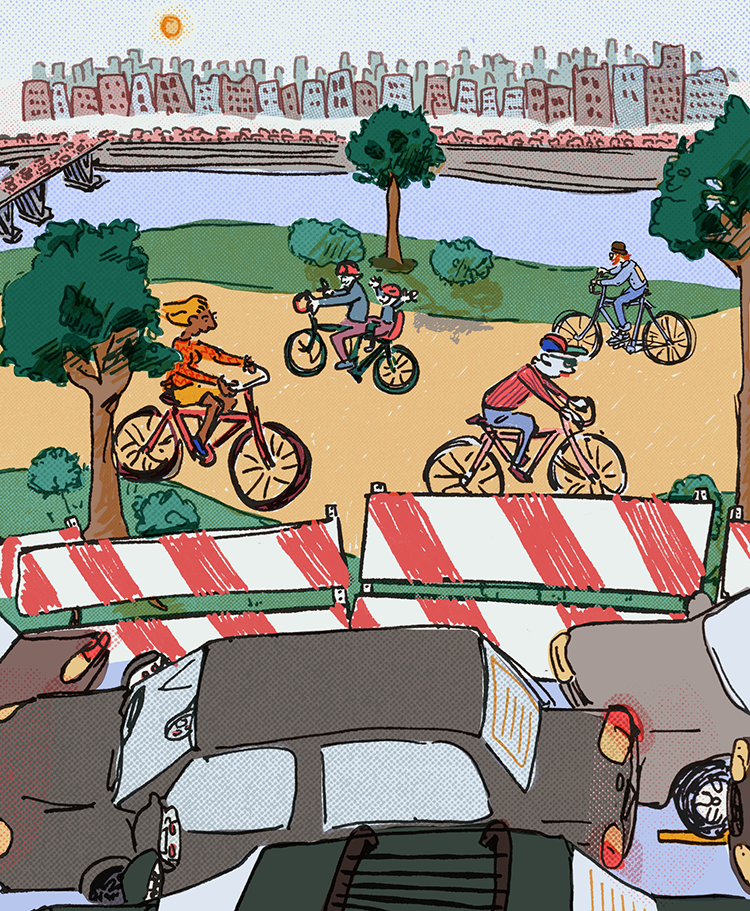

“Music therapy could be delivered by community health facilities like Drexel’s 11th Street Family Health Services. It could be ‘drumming for wellness’ as an after-school program in a safe environment. Music therapy in parks and recreation centers are possibilities.”

People can become vocal advocates for it, he says, “in schools, community centers and with local and regional politicians.”

Rapper Macklemore summed it up well: “Music is therapy … It pulls heart strings. It acts as medicine.”