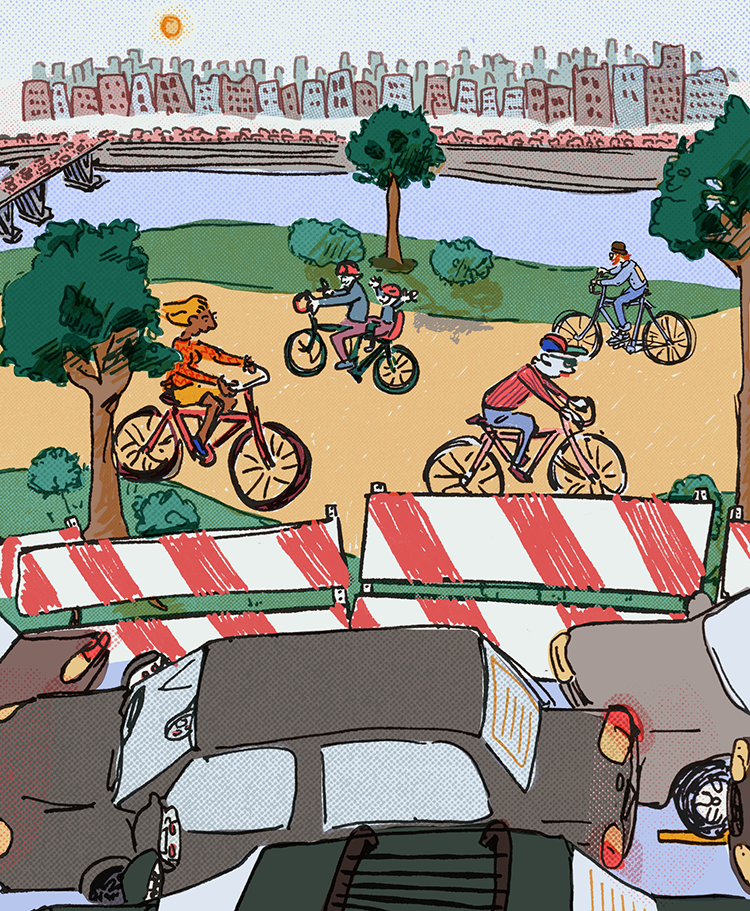

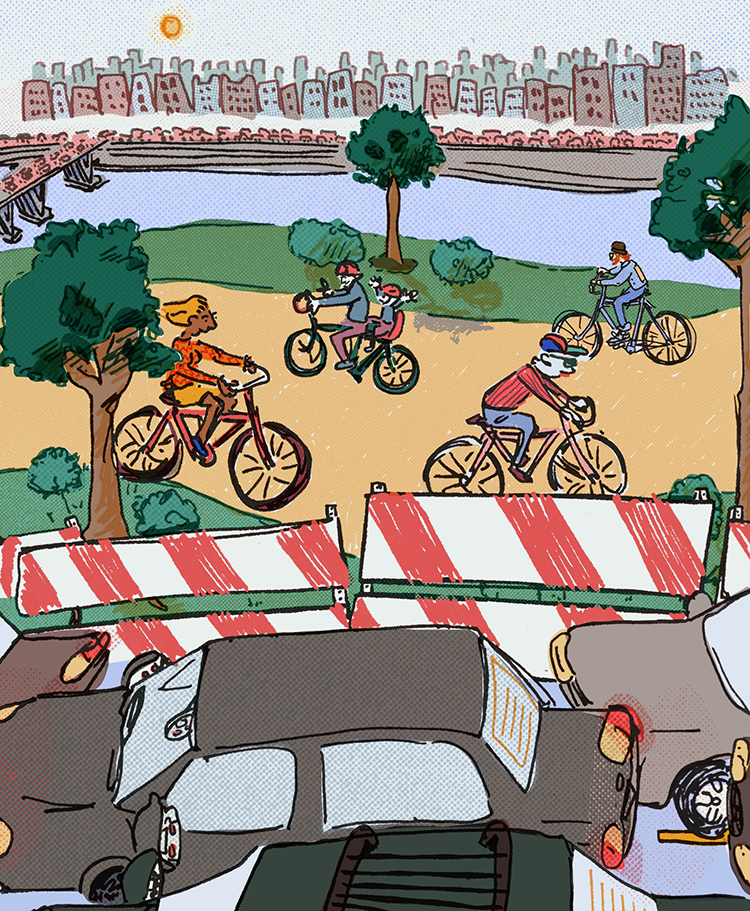

Earlier this year, as policy director of the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, I began meeting with City Council staff, businesses, registered community organizations and nonprofits to discuss the future of Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

The drive has become one of the most trafficked trails in the entire Commonwealth of Pennsylvania since it was closed to motor vehicles in March 2020. According to electronic counts conducted by the engineering firm WSP, the drive sees more than 5,000 users per day on weekdays and more than 9,600 people per day on weekends. While we don’t have pre-COVID weekend counts to compare, we do have weekday counts. The WSP data, when compared to the city’s data, shows a 1,300% increase in users on weekdays, which is the fastest increase in usage of any trail in the area we are aware of.

Keeping this in mind as vaccinations inch us back to normalcy, it’s time to reimagine the drive’s future.

“For decades, there has been a line of thinking that, if we just add one more lane, congestion will decrease. But the opposite has always been true.”

My colleagues at the coalition and Yasha Zarrinkelk, of Transit Forward Philadelphia, have discussed two proposals for the future of the drive: leaving it as it is, an open street for the public, or making it a shared roadway, split in half, with pedestrian traffic on one side and a two-way busway on the other, making travel easier between Center City and Northwest Philadelphia and West Philly neighborhoods Mantua, Wynnefield and Parkside.

The initial feedback we got was virtually all positive, which was a surprise to me.

What I expected were questions about how closing the drive affects traffic patterns and how traffic on I-76 and Kelly Drive, which run parallel to MLK Drive, would be affected long term by the closure.

These questions can’t be answered definitively until studies are conducted, looking at expressway usage, how long SEPTA takes to return to full capacity and what commuting looks like post-pandemic. But what we can say is that adding MLK’s two lanes back for Center City commuters won’t lighten the amount of traffic they see.

Despite what you’ve heard, traffic is actually created by additional motor vehicle lanes. So if you’re inching along I-76 while MLK Drive is closed to vehicles, you’ll be inching along I-76 with it open to vehicles, too.

For decades, there has been a line of thinking that, if we just add one more lane, congestion will decrease. But the opposite has always been true. Increasing roadway capacity encourages more people to drive, thus failing to improve congestion. This is a concept called “induced demand.”

As noted in a recent Inquirer story about snarling traffic on Philadelphia highways and efforts to ease congestion, Thomas K. Edinger, who runs congestion management process programs at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, noted: “To manage congestion, we have to rely on other ways of reducing traffic versus building more capacity,” adding that it is well known that expanding roads induces more traffic, making them “as crowded as before.”

Sure, in the case of MLK Drive, lanes were taken away—but it’s been that way for more than a year now. While the number of vehicles going in and out of Center City is about 80% of pre-pandemic levels, commuters have adjusted to the new restrictions—and they will adjust again when restrictions drop and more commuters head back to work.

There are cases in which highways have been destroyed for the good of a city’s health, and traffic simply finds another way. There are examples of this all over the world, spanning decades, including freeway teardown projects in Milwaukee and San Francisco.

The U.S. government has finally caught on to this. A recent Senate bill would provide $10 billion to cities for tearing down urban highways, which are unsightly, noisy, dirty and have historically destroyed low-income neighborhoods.

Creating less expressway space for motor vehicles is a net good if you care about road safety and climate change. The best case scenario for a person sitting in traffic, alone in their car, is for that person to say, “Wow, this sucks. I’m not doing this again,” then choose a different route or mode of transportation next time they travel into the city. And two bus-only lanes on MLK Drive could be the driving force that gets those commuters out of their cars and onto the bus. (Public transportation will need all the support it can get: SEPTA saw a 92% drop in ridership on buses, subways and trolleys and a 98% drop on Regional Rail between March and June 2020.)

Additionally, we must keep in mind that with white collar jobs shifting to remote work, it’s still unknown how many jobs will be coming back to Center City. Many cities are already preparing for the work-from-home trend to continue, and Philadelphia should do the same. In doing so, we can reimagine our spaces for living and our roads for travel beyond the commute, with buses and trains transporting people to and from communities, cultural centers and public spaces.