Years ago, my parents told Miss Farber, a white 60ish teacher at the elementary school in our Black working-class neighborhood, that when my brother and I graduated they would enroll us in a junior high program for gifted students.

“There’s a Hebrew element at that school,” Miss Farber said, “and your children won’t make it.”

My folks ignored her.

Fast-forward 15 years: My brother had graduated from Harvard Law School and I’d earned a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania.

Today, many white teachers still envision small lives for their Black students.

“It’s about the way you see other people’s children,” says native Philadelphian Sharif El-Mekki, founder and CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, aka the Center. President Obama and Oprah Winfrey praised El-Mekki for the huge strides his students made during his tenure as principal of Mastery Charter School Shoemaker Campus from 2008 to 2019.

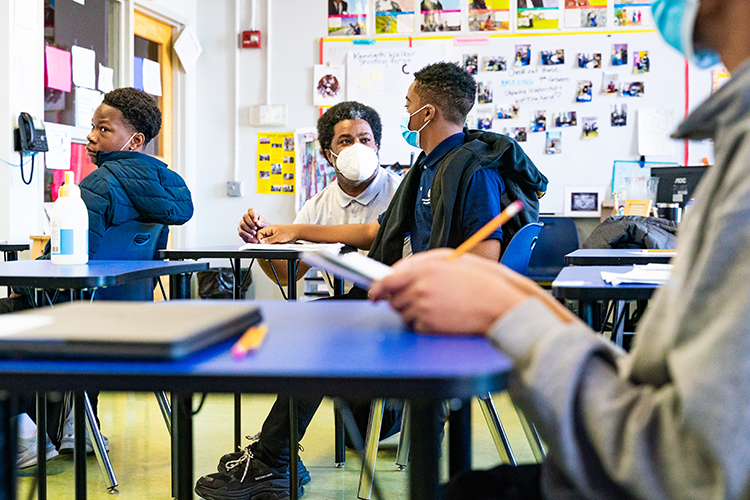

The Shoemaker students’ success underscores what research has shown: Teachers of color expect—and get—more from students of color, according to a report cited in “The State of Racial Diversity in the Educator Workforce,” published by the U.S. Department of Education in 2016.

“Many students of color see improved academic performance, increased graduation rates, lower likelihood of suspensions and higher rates of college matriculation when … taught by Black teachers,” says Michael Hines, assistant professor of education at the Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE). “Additionally, many Black teachers come from the very communities they serve, giving them the deep roots and lasting commitments … critical to building successful schools.”

A blizzard of other studies, including “The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers,” published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2017, show that Black students who have Black teachers in elementary school fare better.

It’s also crucial for “white students to see teachers of color in leadership roles … in their classrooms and communities” to counter distorted images in the media, according to former Secretary of Education John King Jr.

But schools in Philly and nationwide face a roadblock: too few Black teachers.

“In Philadelphia more than half the students are Black while barely a quarter of the teachers are,” El-Mekki says. The Center aims to help solve that problem.

A lifelong educator, El-Mekki nearly missed becoming a teacher. “I was on my way to law school,” he says. “I made a commitment to be an activist, and I wanted to effect change through the legal system. Then the parent of a friend, Mother Cynthia Moultrie, told me about a program recruiting Black teachers. Thanks to that program, I saw that I could be an activist through teaching.”

“In Philadelphia more than half the students are Black while barely a quarter of the teachers are.”

— Sharif El-Mekki, founder and CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development

In 2014, El-Mekki launched The Fellowship: Black Male Educators for Social Justice, an organization to help recruit and retain Black male educators in Greater Philadelphia. (According to the Stanford GSE, Black men account for 2% of U.S. teachers.)

Then El-Mekki took things a step further. “I couldn’t stop thinking about what it would … take to build a national Black teacher pipeline,” he says. “Our vision for the Center not only included Black women, but a framework rooted in Black history and Black pedagogical practices that supported the development of antiracist mindsets and … included competencies such as addressing microaggressions.”

El-Mekki launched the Center in 2019. “We seek to revolutionize education by increasing exponentially the number of Black educators so that low-income Black children and other disenfranchised young people can reap the benefits of a quality public education,” he says.

The Center’s Black Teacher Pipeline cultivates young educators by giving them the experience of teaching in summer Freedom Schools that boost the literacy of first-, second- and third-graders. College and high school students teach in a six-week Afrocentric program, earn a stipend and receive three or six college credits.

“The students see the children’s academic progress and come to view themselves as activists,” El-Mekki says. “In 2021 we offered a virtual site and added three in-person sites in Greater Philadelphia and Camden, enrolling a total of 233 scholars in Grades 1 through 3, a 120% increase from last year.”

For professional development the Center draws on a corps of seasoned administrators and teachers to help young educators and career changers, El-Mekki says. “We use a mix of instructional presentation, dynamic discussion and practice. Many of our mentors have helped turn schools around.”

Their policy work involves meeting with legislators at the city, state and federal levels to shape laws and decisions that can better public education for disadvantaged students. The Center co-sponsored Aspiring to Educate in 2019, a program designed to recruit and retain more diverse teachers and school administrators.

The Center also relies on partnerships to achieve its goals.

“We’re looking for like-minded partners who believe that Black educators can play a powerful role in uplifting the profession and the city’s children,” El-Mekki says. “For example, we work with the United Negro College Fund to provide scholarships for future educators.”

John Bailey, 20, a student at the Community College of Baltimore County, taught a virtual Freedom School class this summer. “The experience confirmed my desire to become a teacher,” he says.

Bailey learned highly fruitful ways to approach Black students. “We don’t kick scholars out of class [for misbehavior]. We use restorative practices like taking students aside and talking with them.”

For Horace Ryans III, 19, a Morehouse College student, Southwest Philly resident and Freedom School teacher this year, the power of an encouraging classroom climate stood out. “I gained [insights] from simply being with students everyday in a loving environment.”

Freedom School prepares children for success, their families say. “Thanks to Freedom School, [my granddaughter] knows prefixes, suffixes and root words, and she’s only going into second grade,” says Toya Algarin, 59, of Germantown.

El-Mekki counts on the community for support. “Community members, including high school students, took part in focus groups that helped us design our curriculum,” he says.

Community activist Elaine Wells, 54, volunteers in the Center’s program for parents, offering tips on how to get the best results from schools.

“I have three Black sons who went through the Philadelphia school system,” she says. “I share what I learned during those years.”

“What we’re doing isn’t new,” El-Mekki says. “We’re giving a 2020s update to an idea James Baldwin voiced years ago: to teach Black children is a revolutionary act.”

To learn more about the Center, which welcomes donations and sponsorships, visit thecenterblacked.org.