About 120 years ago a nature enthusiast named Charles McIlvaine explored the Angora Woods of West Philadelphia hunting for mushrooms. While most of the Angora Woods have long since been built up, a fringe of the area remains along Cobbs Creek. It was there that I met up with a modern-day fungi enthusiast, Luke Smithson.

We walked down to the creek, stopping to take note of fungi as we went—Phellinus robiniae growing out of black locust trees like wood-colored hockey pucks, and black-ruffled wood ear fungi on a fallen log, similar to the mushrooms you might find in a bowl of hot-and-sour soup. It was easy to imagine a mushroom hunter in an earlier century doing the same: checking tree trunks and turning over rotting logs as he made his way toward the water.

Along with Angora, McIlvaine explored other areas such as Fairmount, Wissahickon, The Woodlands Cemetery, in addition to locations beyond Philadelphia, like Mount Gretna in Lebanon County.

He sampled mushrooms as he went, behavior rightly regarded as reckless today as well as in his own time. The naturalist held tight to the belief that such was justified “to personally test the edible qualities of hundreds of species about which mycologists have either written nothing or have followed one another in giving erroneous information,” he once wrote.

“While often wishing I had not undertaken the work because of the unpleasant results from personally testing fungi which proved to be poisonous, my reward has been generous in the discovery of many delicacies among the more than seven hundred edible varieties I have found,” McIlvaine continued.

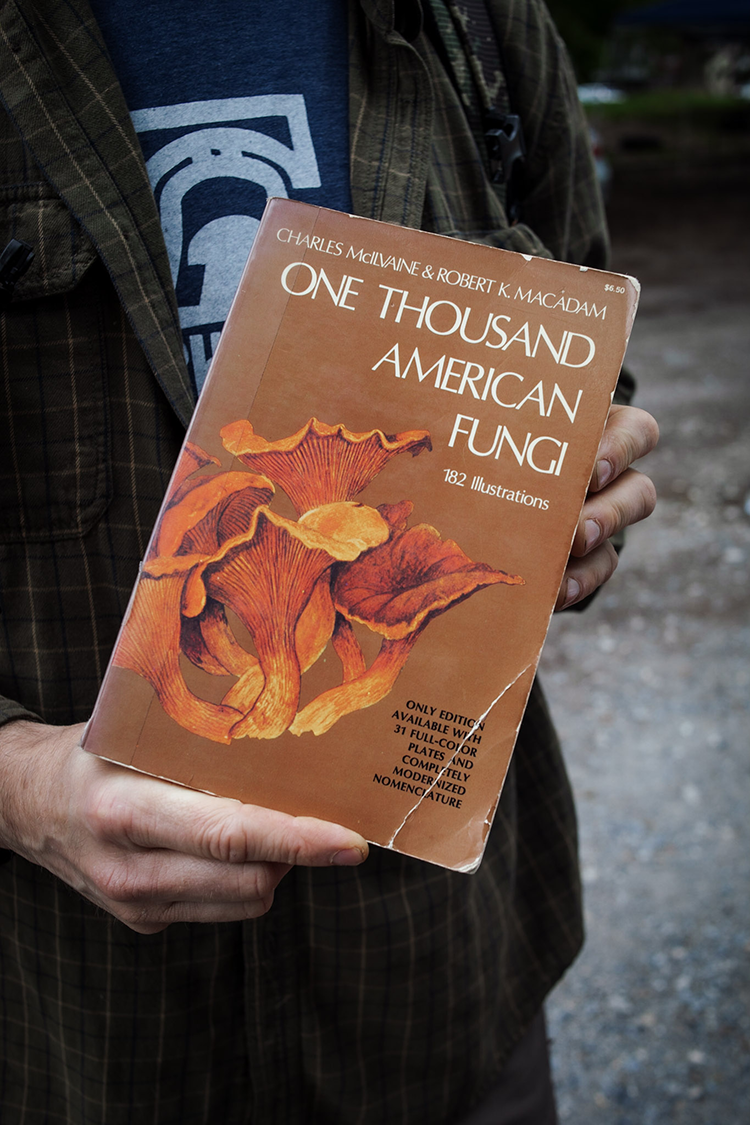

“I said, ‘I have this old book here—I wonder how much of this stuff is still out there.’”

—Luke Smithson, fungi enthusiast

The product of all his hunting and daring taste-testing was, for its time, a monumental book about North American fungi: “One Thousand American Fungi.”

Smithson first heard of McIlvaine and his book from a speaker at a mushroom festival. Later, a fungus expert suggested he reexamine the author’s findings.

“She recommended that a good amateur project would be to dig into old records and see what’s still there. Something clicked and I said, ‘I have this old book here—I wonder how much of this stuff is still out there.’” Smithson says.

Both McIlvaine and Smithson got into mushroom hunting through their taste buds. McIlvaine writes that while he was living in West Virginia he rode his horse through forests full of beautiful mushrooms. “It occurred to me they ought to be eaten,” he wrote.

Smithson, as a chef, met a mushroom hunter at the restaurant where he worked. The chance encounter made Smithson think back to when he himself had sold foraged mushrooms to restaurants as a teenager. Inspired, he headed out into the woods again and didn’t stop.

Although Smithson has been hunting the same places McIlvaine did, a lot has changed in fungi, and in Philadelphia, in 120 years. McIlvaine collected his fungi samples in the countryside at the edge of the city. Since then, the countryside has been built up, so that the pastures and oak woods have largely been replaced by densely built row houses and apartment buildings.

The woods that remain, including their fungi, are also different.

The mushrooms we notice on the surface are the fruiting bodies (reproductive parts that release spores) of organisms that mostly live as networks of thread-like structures called hyphae. Some grow into and feed on decaying wood, but others grow in concert with trees, sharing nutrients through their roots. Many trees that McIlvaine knew have since disappeared. Chestnuts and elms, for example, have been mostly wiped out by invasive pests. They took their fungi companions with them.

The actual organisms that do remain might be the same, but not in name.

Scientists have since realized that some species named separately are really the same thing, so they get lumped together and only one name is kept. A researcher like Smithson won’t necessarily find the old name mentioned in newer texts. In the other direction, some species have since been recognized to actually contain multiple fungi that should each be elevated to the status of species. The original species gets split up, with new names given. The result is a mess that has to be reconciled with the current taxonomy.

“The biggest part of the project is just modernizing those names and figuring out what he was talking about,” Smithson says. “From 120 mushrooms for which McIlvaine provided specific locations, I whittled it down to 94 that are specifically Philadelphia. Of those 94, 15 are still completely unintelligible.”

That has left 79 to track down. Smithson invited other local fungi enthusiasts to take part in the hunt. He set up a project page in the citizen science platform iNaturalist to organize modern observations of McIlvaine’s fungi and organized outings with the Philadelphia Mycology Club (PMC) starting last year.

“We did about a dozen trips through the summer, focusing on Bartram’s Garden and Cobbs Creek,” Smithson says.

As of publication, Smithson’s project has tracked down 41 of the fungi they’re looking for in Philadelphia, including one that was first described as a species from specimens collected by McIlvaine.

“Last year when I expected it to be fruiting, I basically put up a wanted sign on the PMC Facebook page, and someone found it in the Wissahickon,” Smithson says. “It’s called Tylopilus badiceps.”

Smithson describes it as a large, porcini-like mushroom.

“A pretty impressive looking mushroom. McIlvaine collected it 120 years ago and it still exists in the city.”

While it appears the names of some of the mushrooms have changed since McIlvaine’s time, one thing it seems has remained the same: the fervent enjoyment enthusiasts take in hunting for them.

As the 20th-century naturalist wrote, “the delights of a mushroom hunt along lush pastures and rich woodlands will take the rank of the gentlest craft among those of hunting…”