Imagination ran wild this year as activists and protesters envisioned a city much different than the one we live in.

Philadelphians marched down Broad Street, climbed the Philadelphia Museum of Art steps and gathered at Malcolm X Park in West Philadelphia, demanding change with chants, signs and determination. Temple University communication professor Jason Del Gandio notes that the same unrest swept other cities too.

“The patterns we’ve seen are the same ones we’ve seen across the country,” Del Gandio, the author of Rhetoric for Radicals: A Handbook for 21st Century Activists, says. “An attempt at trying to reimagine the nature of American society.

The year began with the Republican-controlled Senate’s acquittal of President Trump in his impeachment trial, a move that sparked tension in Philadelphia’s deep blue streets.

From there the political tension only grew.

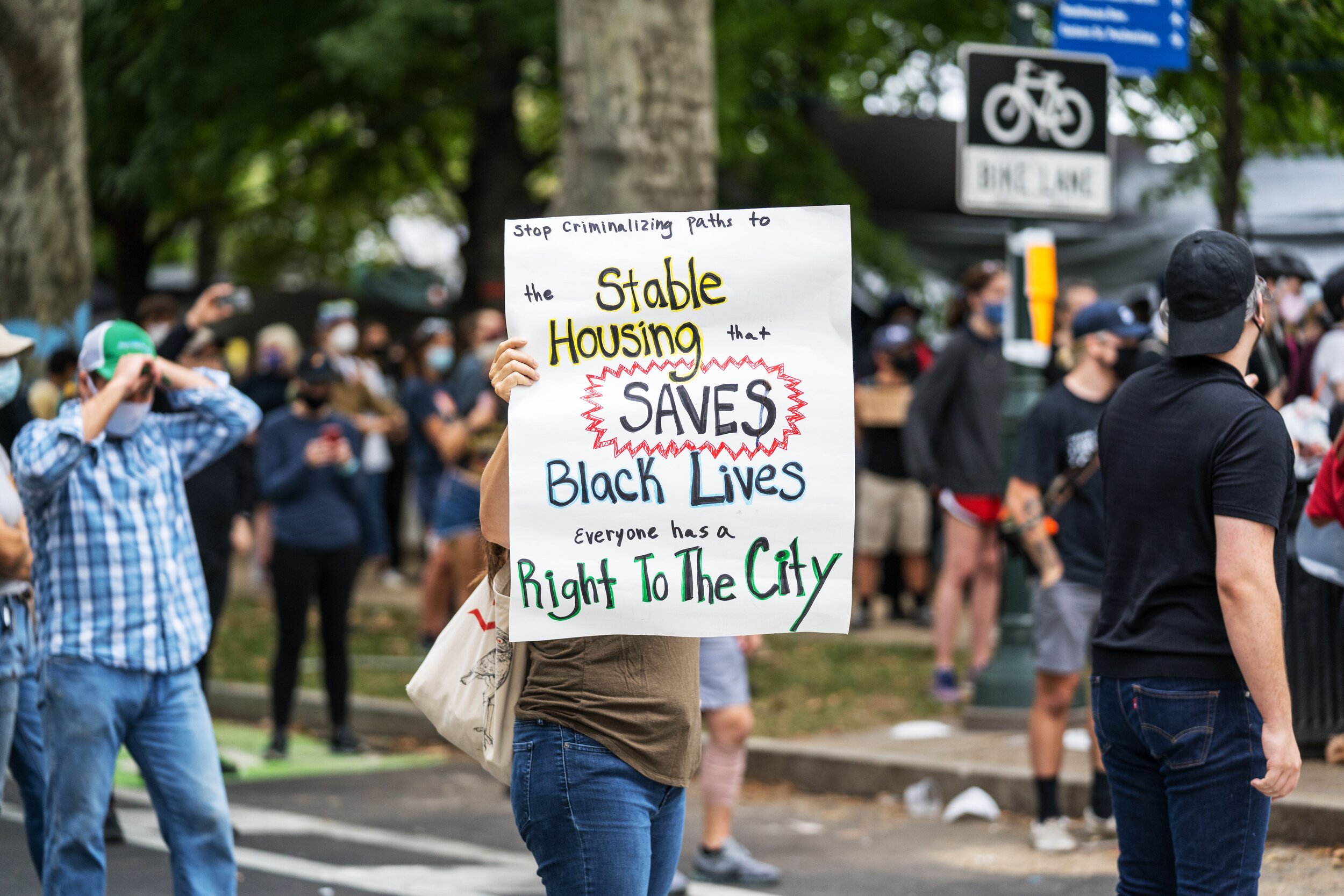

The pandemic-induced state lockdown in March plunged citizens and businesses alike into economic distress. The country was rocked on May 25, when a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on the neck of George Floyd, a Black man, for allegedly using a counterfeit $20 bill—resulting in the 47-year-old man’s death. Activists demanded better from the new owners of the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery after an explosion had forced the plant to shutter last year, giving nearby residents fresh air again. Homeless Philadelphians demanded adequate housing from the city. And when the presidential election came in November, Philadelphians took to the streets to demand that every vote be counted in the face of baseless voter fraud allegations lobbed by the sitting president and his supporters.

Failed systemic structures were the theme of 2020, Del Gandio says, and though there were many different movements, they all represented the same thing: an overall indictment of the system.

“The best way to put it is, ‘If the system doesn’t benefit you, why should you support the system?’” Del Gandio says.

Call for police reform; rethinking the men and women in blue

As Minneapolis protested Floyd’s death May 30, in Philadelphia people gathered at the Art Museum steps, holding signs with messages like,‘End police brutality’ and ‘Black Lives Matter’.

When the clock struck 4 p.m.; sparks flew. Residents, engulfed with rage, flooded Center City, some breaking into and looting stores. Looters also hit West Philadelphia’s 52nd Street Shopping Center, Wynnefield Heights’s Target, and Walmarts in North and South Philadelphia, among others. That night was the beginning of a seven-day-long, city-wide protest.

Del Gandio says the property destruction could be seen as backlash against the white supremacy construct, which both policing and the entire landscape of profitable America are borne of.

“If you come to the conclusion that that’s [police brutality is] a systemic problem, then everything’s fair game,” Del Gandio says. “It helps to explain why people would destroy buildings. Would destroy cop cars. Would destroy Walmarts.”

On June 1, the National Guard arrived in Philadelphia. While soldiers were stationed in full military gear; helmets, vests, and rifles, residents did not stand down or censor their message.

On the afternoon of June 1, police used tear gas to separate a group blocking a I-676. One officer is now facing aggravated assault charges for striking a student protester in the head with a metal baton. Meanwhile, some protesters incited violence too.

Steve Overlander was among groups maced on I-676. He says the crowd followed a woman with a microphone onto the highway, accompanied by a little drum line.

“We saw State Police. They had people back up and clear the highway,” Overlander remembers. “They had cleared about 300 yards between us and them and they just started launching teargas.”

With similar occurrences across the nation, conversations around defunding the police traveled fast. They arrived in Philadelphia mid-June. City artists and groups like the Black Philly Radical Collective and Poor People’s Campaign demanded the Philadelphia Police Department be defunded for the 2021 fiscal year—“defunding” meaning to redirect government money set for the police department to other areas of the city.

Megan Malachi, of the Collective, says the organization’s demands are a result of its greatest minds reimagining what protection looks like without the men in blue.

“We want to be able to have people who are trained in issues of domestic violence and gun violence actually go into communities and solve these issues,” Malachi explains. “Rather than what the police do currently, which is either create more violence or just continue to fuel the system of mass incarceration.”

Del Gandio says new solutions like these—ideas to replace our government’s failed systems—are the highlight of 2020’s activism.

“When there’s a call to defund the police, you have to put something in place,” Del Gandio says. “What do we replace the police with? There’s numerous groups in Philly that are working on these kinds of projects. And they emphasize it’s not just a subtraction—but also an addition.”

As the George Floyd protests died down, Philly activists continued to organize against brutality. Solidarity rallies and protests were held for 29-year-old Jacob Blake, a Black man shot in the back by officers in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and two months later, when 27-year-old Walter Wallace Jr. was shot by two police officers in West Philadelphia Oct. 26.

In video footage of Wallace’s shooting, viewers see him holding a knife and stepping toward police before they began shooting. His parents have said he was experiencing mental health distress at the time, and that the police should have used a taser. Police body camera footage released on Nov. 4 shows officers Sean Matarazzo and Thomas Munz approaching Wallace, and one of two saying “get him” and “kill him.”

District Attorney Larry Krasner said the video is painful to watch at a press conference in November and acknowledged the department’s failure to protect all citizens.

“Especially those who are Black or Brown, as we continue making measurable steps toward building equity, inclusive and public safety in our city, releasing this footage is a step, but also an indication of this failure,” Krasner said.

The affordable housing deal no one will forget

A fight for affordable housing took a strong turn when around 50 people facing homelessness in Philadelphia decided to call the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the highly-trafficked tourist area, home. The James Talib-Dean Encampment was an organized tent community on the Parkway that, along with several other Philadelphia homeless encampments, demanded affordable housing from the city and the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

The encampment began in mid-June when people lined the Parkway with tents and placed a black banner with large white letters that read, ‘Housing Now’ across the camp’s entrance. At its peak, their community consisted of hundreds of Philadelphians.

But the Parkway or other locations were not their permanent home. As the banner read, the residents desired affordable housing and on Oct. 27, their demands were met. Fifty properties will now be transferred from the City to a community land trust controlled by encampment residents. Members of the encampment will be granted properties originally scheduled for sale by PHA; unaffecting the 40,000 people on the waitlist.

JTD organizer Jennifer Bennetch says their success was a long time coming.

“Something had to change; we had to take a stand,” Bennetch says. “Some people thought we should just give up, but personally, I always knew that we would get something if we kept going.”

Activism on your plate

The coronavirus pandemic highlighted several failures in the America system, including food insecurity. Millions found themselves on the unemployment waitlist, deciding whether to pay bills or provide food for their families. But food justice activism came to the rescue with more than 30 mutual aid programs popping up all over Philadelphia; Community refrigerators, fresh produce centers and more.

All are mutual aid projects.

“We’re talking about in terms of everyday citizens working together to benefit each other,” Del Gandio says. “I mean, that’s the definition of mutual aid. Now, that’s a form of activism. Maybe not protest, but it’s definitely full of activism.”

However, these mutual aid projects fit the bill for protest when you think of them as local organizers’ expressions of objection to chronic hunger. Pre-pandemic approximately 20% of Philadelphians were estimated to be food insecure.

“They call it mutual aid because it’s not like a charity. It just starts with one person,” Jane Ellis the founder of the Germantown Fridge says.

The Germantown Supply Hub, a Northwest Philadelphia mutual aid program, grew from a group of George Floyd protesters. The Black-led group created the program when the city food programs did not suffice.

Ashley Davis, one of its 12 organizers, says although the Supply Hub birthed from the unrest, it will now be a permanent neighborhood entity. Davis says the mission of the Hub is to provide a ‘Free Market’ for the people where food and experiences are shared.

“Beautiful conversations spark,” Davis says. “People share recipes, food, dreams of gardening—and that’s what we do here [at the Supply Hub]. We share.”

A right to clean air in Philly

A breath of fresh air should not be a privilege; environmental activists raised their voices this year with the goal of making clean air accessible to all, regardless of race or class.

In June 2019, an explosion marked the end of a Southwest Philadelphia gas plant that had been polluting the air of a predominantly Black neighborhood. Since the Philadelphia Energy Solutions explosion led to bankruptcy, an explosion of activism followed. After enduring the gas plant for more than 150 years, neighbors and activists are demanding the property’s new owner, Hilco Redevelopment, be environmentally conscious.

“It’s gotten better for us,” Rodney Ray, a member of the environmental organization Philly Thrive, says. “Before you could ride the bridge in the summertime in South Philadelphia and smell the fumes. But now that it’s closed, you don’t smell it as much.”

Philly Thrive has been raising awareness about the refinery’s negative public health impact. Its activists gathered roughly one year from the date of the explosion to protest environmental racism at the site. Ray, 67, lived three blocks from the former PES plant with his grandfather for 25 years, but his relationship to the property goes deeper. The retired Union worker worked at the plant for four years in the early 1980s. Looking back, Ray says he felt that he and neighbors were directly affected by air pollution; now a direct reason for his activism.

“I’m a union worker too, but I knew that I had to stand up and tell them the truth about the workplace, it not being a healthy workplace,” he says.

Moving forward, Philly Thrive, the Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation at Drexel University and more organizations, is working closely with Hilco to ensure the new development benefits the community. Hilco is taking its first step by cleaning the property and removing materials like tanks and chemicals.

While everyone’s rooting for an environmentally-conscious property, Philly Thrive is also hoping jobs will come with the new development. When the plant closed, more than 800 jobs were lost.

“That’d be the first step,” Ray says. “Getting some community work.”

Philadelphia’s city-wide Election Day party

On Saturday, Nov. 7 when media outlets pronounced former vice president Joe Biden the president-elect of the United States, Philadelphians took to the streets. City residents celebrated and danced the sound of car horns, cowbells and music.

“Philly give it up for yourselves,” activist and program director of Girls Rock Philly Samantha Rise said to gatherers at City Hall that day. “Give it up to the cross class, cross race, intersectional, inter generational movement that made this win possible. Give it up for the queer leadership, give it up for the Black leadership, give it up for undocumented leadership, give it up for the refugees, and the least of these who made this win possible for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.”

While the presidential election’s outcome marked one systemic victory to many Philadelphians, regardless of national leadership, Del Gandio predicts that activists will need to continue pushing for reform to truly move the needle next year.

“Activism will be needed in 2021,” he says. “Just like it was in 2020.”

Rise indicated as much at City Hall the day the election was called.

“This win is for us and we will not stop until our voices are represented in the policies and practices of any administration that takes office,” Rise said. “This is not over.”

Jason Peters contributed to this article.