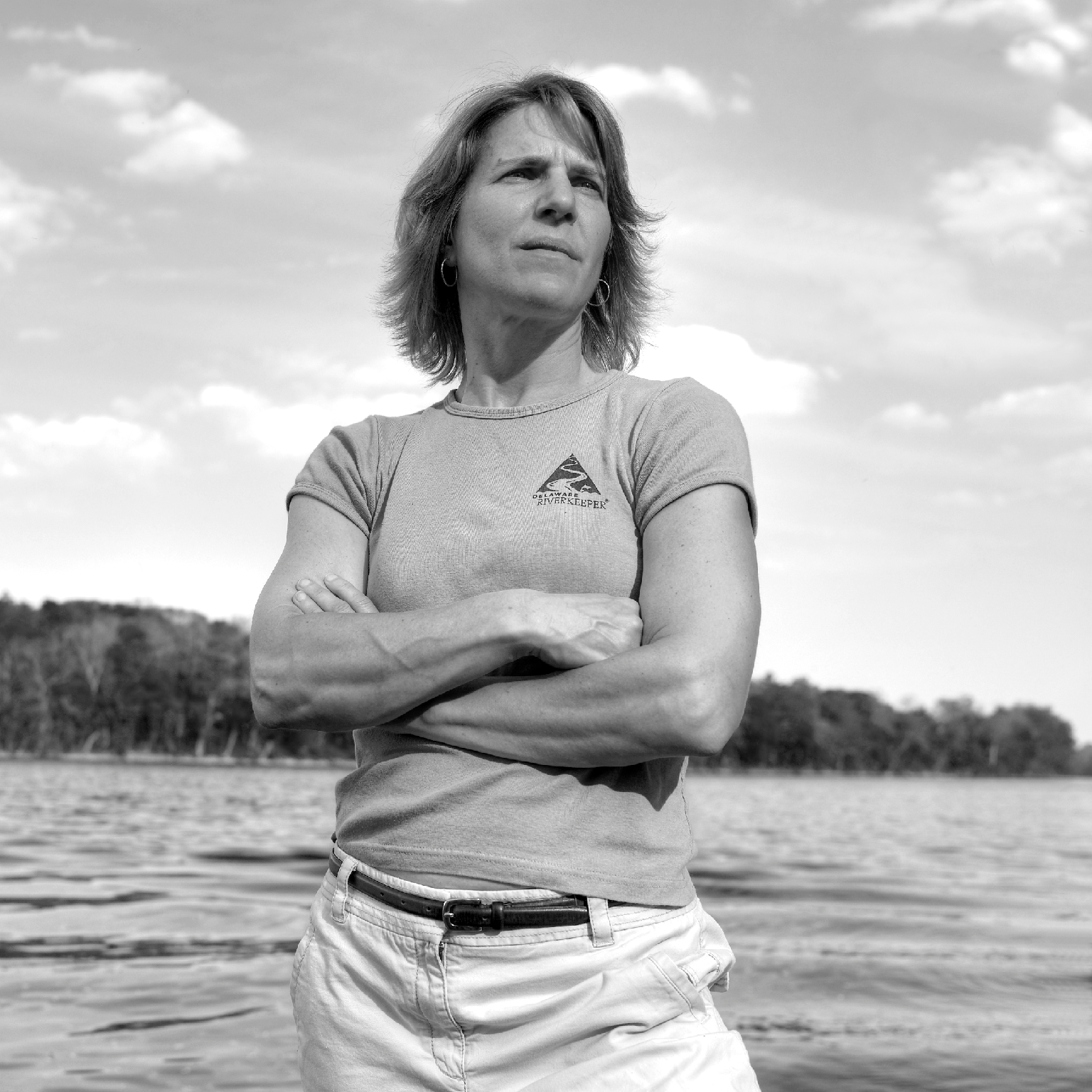

Photograph Courtesy of Delaware Riverkeeper Network

An Upstream Battle

By Emma Kuliczkowski

This march, the Delaware Riverkeeper Network and other environmental organizations like the Clean Air Council, PennFuture, Environment New Jersey and Clean Water Action petitioned the Delaware River Basin Commission to increase regulations on pollutants discharged into the Delaware River for the sake of those that use the water for recreation.

“As you are aware, the Delaware River has come a long way from its polluted past in the late 1800s to mid 1900s,” the petition reads. “Even as late as 1964, on the order of a million pounds of waste was being freely discharged into the Delaware River every day, and more than 60 percent of that was coming from sewage treatment plants, predominantly from Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington. In that same year, the bacteria count at Philadelphia’s water intake at Torresdale was 39,300 fecal coliform units per 100 mL. In addition, slaughterhouse waste, chemical plant waste and acidic industrial waste were also freely dumped into the River.”

Thanks to the Commission’s Water Quality Regulations Act, passed in 1967, and the federal Clean Water Act, passed in 1972, the Delaware’s condition has drastically improved in the last several decades.

Currently, the Philadelphia-Camden portion of the river is considered clean enough for surface recreation—like kayaking, paddle boating and canoeing—but not safe enough for people to come into physical contact with the water. The groups’ petition requests the Commission enhance its protections of this portion of the river, which starts at the mouth of Pompeston Creek, in New Jersey, and ends at the Commodore Barry Bridge.

According to Maya K. van Rossum, the leader of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, the point of the petition is to ensure that the Philadelphia-Camden portion of the Delaware River is held to the same water-quality standards as the rest of the river, in order for the water quality to improve enough so that activities that involve primary contact (physical contact) with the water—like swimming, jet-skiing and tubing—would be permitted.

It’s the smart thing to do, she explains, because the river is already being used this way. The petition seeks to hold the commission accountable.

“State and federal agencies and the Delaware River Basin Commission are not recognizing that primary-contact recreation is happening,” Van Rossum says.

“The reality is that people are coming in primary contact with the water,” she explains. “They are swimming in the water, they are jet-skiing in the water, and they’re even doing yoga on paddleboards, where it’s very easy to fall into the water.”

One concern is Philadelphia’s Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) system, which pushes sewage into this section of the Delaware, usually after excessive rainfall, when the high water levels overwhelm the city’s sewers. Philadelphia is certainly not alone in the struggle against the impacts of CSO systems. According to New York State’s clean-water advocacy organization Riverkeeper, more than 27 billion gallons of raw sewage and polluted stormwater goes into New York Harbor each year through CSOs. Estimates from the United States Environmental Protection Agency state that roughly 19 billion gallons of untreated sewage and runoff entered waterways in Detroit; Cleveland; Toledo; Buffalo; Hammond, Indiana; Chicago; and Milwaukee between 2010 and 2011.

Other industries guilty of discharging excess contaminants into the Philadelphia-

Camden reach of the river, according to the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, include the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority, Paulsboro Refining Company, Exelon Eddystone, Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Evonik Corporation and Philadelphia Gas Works. None of the above entities returned our request for comment concerning the petition and their emissions into the river in time for publication.

The Delaware River Basin Commission offers maps on its website that show certain dischargers within the area.

The Philadelphia Independence Seaport Museum is one group that hosts various secondary-contact recreational activities such as kayak excursions and paddle boating within the Philadelphia-Camden stretch of the river.

As Ali Stefanik, assistant director of waterfront and community programs at the Seaport Museum explains, during the warmer months, it usually offers kayak excursions, paddle boating and leadership programs on the Delaware for high school students.

“We try to center all of our programs around the river because the health of the river is so important to all of us,” she says. “Whether you’re using the river for recreational activities or you just live in the city and drink our water.”

“We want to be cognisant that the river could always be cleaner,” Stefanik says.

The Seaport Museum takes precautions when CSOs occur. After heavy rains, it ceases water-related activities until the water quality is up to standard. The museum monitors the quality of its water regularly through its educational River Ambassadors program.

According to Stefanik, the museum also has a good working relationship with the Philadelphia Water Department, so it can stay up to date with what’s happening in the river.

The petition has received pushback from industry and government agencies.

Laura Copeland, public relations officer for the Philadelphia Water Department, explains that activities like swimming and tubing are unsafe due to high levels of bacteria, slippery rocks, or potential underwater debris.

“The Philadelphia Water Department is immensely dedicated to working toward the goal of a swimmable river and proud of the water quality progress we have made to date, but we’re not yet in a position that warrants a change in the designated use,” Copeland says.

As of right now, PWD does not plan to make any substantial changes to allow the Philadelphia-Camden stretch of the river to be accessible for primary-contact recreation. However, Copeland says, the water department has already implemented a plan to minimize CSOs that will take place over the next 25 years.

The petition, which was submitted on March 11, has seen no response.

“The Commission has received the letter and petition from the Delaware Riverkeeper Network and other organizations,” Peter Eschbach, director of external affairs for the DRBC says. “Commission staff and the DRBC Commissioners acknowledged receipt of the letter when it arrived and are carefully reviewing the request. A response to the petition is not available at this time.”

Rossum notes that the commission has advanced other requests for natural gas and pipeline companies in a matter of weeks or even days.

“It’s a priority to the people,” Rossum says. “This river belongs to the p

eople. It does not belong to the industry and it does not belong to the port operators.”